| « Back to article | Print this article |

Why ex-bankers will lead the financial innovation race

There would be entrepreneurial exits from the financial sectors over the next few years, and many of these will result in enterprises that will generate value by sharing the benefits of financial innovation more fairly.

Innovation improves efficiencies in existing processes and/or enables development of different versions of products or services, as a result of which the innovator is able to reduce costs and generate extra value.

In most industries, there is generally a short monopoly period during which the innovator earns disproportionate profits; but over time competitors learn these new tricks and, in most cases, customers demand a share in the savings.

Sometimes, people closely associated with the innovation leave the company and set up on their own, pushing the benefits even more rapidly into the marketplace. Thus, most innovations end up as a win-win, with the customer ultimately getting the best of the bargain.

In the banking industry, too, decades of technology-led innovation (ATMs, which became commonplace in the 1970s, are their most visible public face) generated savings for banks and improved costs and convenience to customers.

However, the lion's share of gains from innovations in financial products over the past three decades or so has stayed largely with banks.

Click NEXT to read more...

Why ex-bankers will lead the financial innovation race

While customers certainly benefited from the new products - the ability to eliminate or reduce interest rate risk through interest rate swaps, or credit risk through credit default swaps, for example - the pricing of these complex products remained (and remain) inscrutable.

As a result of this, banks were able to hold on to the outsize "monopoly period" margins for a surprisingly large amount of time.

This doubtless partly explains why financial sector profits as a share of corporate profits (in the US), which ranged between 5 and 15 per cent from 1948 to 1980, soared to reach as high as 44 per cent in 2007.

In normal circumstances, when profits in an industry start rising sharply, it attracts competition, which, over time, brings profits back to their long-run average - that is what a "free" market is supposed to do.

The fact that the financial sector was able to hold on to these gains for so long - even today, the pricing of most structured products is horribly opaque - confirms that there is either inadequate competition or a sustained information asymmetry in the sales of some of the most widely used financial products. Regulators are, a little less blissfully today, asleep at the wheel.

Click NEXT to read more...

Why ex-bankers will lead the financial innovation race

Companies that could afford them recruited bankers who understood how non-transparency was used to pad prices; they were able to capture a slice of the innovation savings.

Some bankers left their comfortable positions to set up boutiques, which were really more of the same from the point of view of customer value.

However, unlike in other industries, very few bankers left their jobs to set up genuinely innovative enterprises, which thrive by delivering maximum value to the customer.

No doubt, many were tempted - when you see such a huge pot of easy pickings, its tempting to try and get some for yourself.

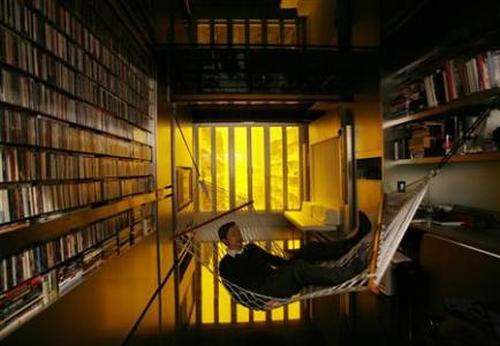

But multinational banks are champions at keeping their star performers in gilded cages: there's always that million-and-a-half bonus coming up in April; and then there's the stock options you'd lose if you left, and, perhaps, a special restructuring coming up in just a few months; and so on.

To be sure, some did jump, but (generally) found that life in a start-up is a different planet from MNC-land. Most of them jumped right back into a cosy cushioned life, which does little to challenge their creativity.

Click NEXT to read more...

Why ex-bankers will lead the financial innovation race

Little surprise then that many bankers - and, here, in the interests of world peace, let me state that when I say "bankers" I mean only those ex-Masters of the Universe who purvey incomprehensible structured trades - become old long before their time.

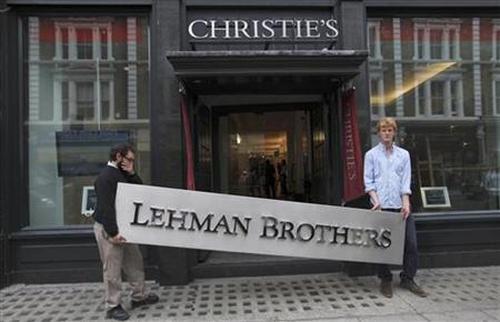

The good news is that the financial crisis has suddenly changed the human resources equation in banking. Not only have there been more than 300,000 job losses on Wall Street (and its environs), but the party - if we could call it that - has reportedly just begun.

Further, being a banker is no longer sexy - Anshu Jain recently admitted that he is sometimes embarrassed to acknowledge he is a banker. While that is doubtless an exaggeration, it is apocryphal.

There won't be as many bankers as there used to be, and they certainly won't make as much money as they used to.

This suggests that we will see far more entrepreneurial exits from the financial sector over the next few years, and many of these will result in enterprises that will generate value by sharing the benefits of financial innovation more fairly.

Regulators would do well to support this trend towards inclusiveness. This is all the more important in countries like India, where much regulation - albeit unintentionally - ends up inhibiting the spread of meaningful financial innovation.