| « Back to article | Print this article |

Why do we swing between drought and flood in India

Why are we still so badly hit, when for years we have been doing everything to drought-proof our agriculture and economy, asks Sunita Narain

It's drought time again.

Nothing new in this announcement.

Each year, first we have crippling droughts between December and June, and then devastating floods in the next few months.

It's a cycle of despair, which is more or less predictable. But this is not an inevitable cycle of nature we must live with.

These are man-made droughts and floods, caused by deliberate neglect and designed failure of the way we manage water and land.

What we must note with concern is that these 'natural' disasters are growing in intensity and ferocity.

We must ask: why are we still so badly hit, when for years we have been doing everything to drought-proof our agriculture and economy?

Click NEXT to read further. . .

Why do we swing between drought and flood in India

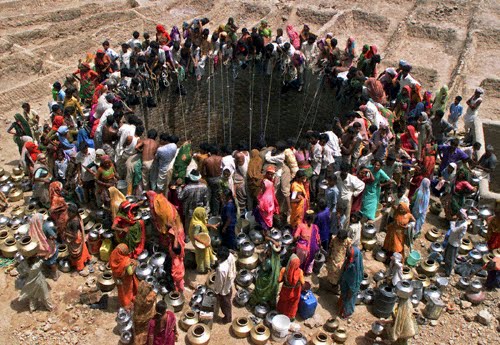

This year, large parts of Maharashtra have been hit by a severe drought.

People are thirsty, crops are lost and livestock abandoned.

Why, when Maharashtra has had the longest programme for drought relief in the country? It was in the 1970s, when the state was similarly afflicted, that it devised the employment guarantee act.

It guaranteed jobs close to where people lived so that they would not be compelled to migrate to cities in times of scarcity.

Since the scheme was to check migration, city dwellers and professionals paid for this programme.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

Why do we swing between drought and flood in India

This scheme was abandoned once its successor – the centrally sponsored national employment guarantee programme -- was launched in the mid-2000s.

The work, however, continues.

Maharashtra has spent furiously on a programme to build irrigation projects.

Since 2006 -- the time farmer suicides in Vidarbha hit the headlines -- the state has been given central grants for water projects.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

Why do we swing between drought and flood in India

According to the state economic survey, in the period till February 2012, Maharashtra spent Rs 12,000 crore (Rs 120 billion) on this alone.

Then, last year, the state received more than its average rainfall -- 102 per cent of normal. So there were rains, schemes and money.

Let's understand how we are going so wrong in our strategies.

First, rainfall is even more variable -- scientists link this to climate change.

In Maharashtra last year, rains were normal, but were either late or erratic.

Farmers lost time waiting to plant the summer crop and then suffered due to intense or unseasonal rains.

An increasingly capricious monsoon makes water management even more urgent.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

Why do we swing between drought and flood in India

Second, though irrigation projects have been built, they have not been utilised.

In this thirsty state, according to its own data, some 40 per cent of the potential created is not being used.

Reports by the Comptroller and Auditor General of India speak about scandalous ways in which dams are built but canals are not, and about cost escalations so high that projects become unviable and are never completed.

Third, Maharashtra is the only Indian state to give industry priority over agriculture in the allocation of water, because there is more recovery of investment.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

Why do we swing between drought and flood in India

So, even when an irrigation project is built, water is diverted to meet urban and industrial needs.

In Amravati, a drought-hit district, the Upper Wardha irrigation project was taken up for implementation under the prime minister's relief package.

But when water started to flow in the canals, the state decided to divert it to the Sophia thermal power project.

Farmers protested vehemently.

This resulted in the overturning of the policy that gave industry priority, but not in the cases where water was already allocated.

Fights go on.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

Why do we swing between drought and flood in India

Today, the state's Economic Survey accepts that only 50 per cent of the utilised water in its reservoirs is being used for agriculture.

With rapid urbanisation, the demand for water will only go up.

This will add to stress unless cities and industries become water-prudent now: use less water and return clean water to farmers, not sewage.

Fourth, water use is grossly inefficient. Maharashtra has a propensity for sugarcane-type, water-guzzling crops.

This dry and water-stressed state produces 66 per cent of the crushed sugar in the country -- far more than what Uttar Pradesh, located in the Ganga basin, manages.

So water available for agriculture is also not used wisely.

Click NEXT to read further. . .

Why do we swing between drought and flood in India

Fifth, we forget that underground aquifers meet a considerable part of the demand for irrigation and drinking water.

So we do not factor in the need for recharge of groundwater. Instead, we extract more and more water, and this leads to scarcity.

The sixth sin is our inability to link investment in watershed and soil conservation to groundwater recharge.

In the past few years, attention has been paid to building ponds and tanks and to protecting watersheds.

But investment in these assets -- coming largely through employment guarantee schemes -- is hardly ever productive.

The schemes provide jobs and do not care about the quality of the work.

Watersheds are planted with trees, but protection of trees is not ensured.

The tank is desilted, but the channels or the catchment that bring water to the tank are not.

In this way, we have made droughts perpetual -- rain or no rain, money or no money.