Photographs: Reuters Anatole Kaletsky

The outlook appears to be improving as policy shifts away from austerity and toward growth.

Strange things have been happening in the world economy and financial markets this week. While that sentence could be written almost any time in the past five years, since the outbreak of the global financial crisis, the strangeness this week has taken a particular form that reveals more than it confuses.

Almost all the economic news recently has been favorable, or at least better than expected. US home values have risen more than at any time since 2006, job losses are down and consumer confidence has been restored to pre-crisis levels.

Japan has enjoyed its fastest growth in years, with evidence mounting of stronger consumption and rising wages.

Even in Europe, the outlook appears to be improving as policy shifts away from austerity and toward growth, with the European Commission no longer pressing governments to hit their deficit targets. Meanwhile, the European Central Bank hints at the possibility of negative interest rates and other extraordinary stimulus measures.

But financial markets have reacted to all this good news by becoming more volatile - panicky, even - than at any time this year.

Although the U.S. stock market briefly hit a record high on Tuesday, prices quickly slumped. Meanwhile, Japanese shares have suffered their steepest fall since the 2011 tsunami. Most importantly, bond markets have collapsed the world over, pushing long-term interest rates in the United States, Japan and much of Europe to their highest levels in more than a year.

Click on NEXT for more...

What's behind the spooked stock market?

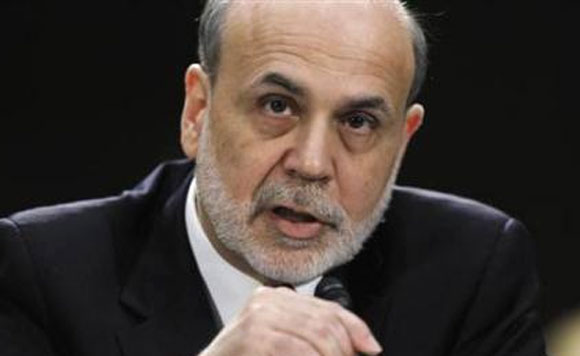

Image: US Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke.Photographs: Kevin Lamarque/Reuters

What is going on?

The clues are provided by the last market upheaval, the one in interest rates and bonds. Plunging bond markets have spooked equity investors because share prices are related in one way or another to the yields on US, Japanese and European bonds. And fears about volatile interest rates and wild stock market gyrations could soon infect consumers and business decision-makers in the non-financial world.

These fears raise three questions.

What is causing the sudden financial anxiety? Are these worries justified? And should policymakers do anything to calm the markets, or alternatively to break the link between gyrating financial markets and the non-financial economy of consumption, business investment and jobs?

The answers are surprisingly clear. There is not much dispute that the outbreak of volatility has been caused by the US Federal Reserve Board - specifically by last Wednesday's congressional testimony from Ben Bernanke and the publication of Fed committee meetings a few hours later.

While I argued in this column last week that Bernanke said nothing new, merely reiterating the Fed's commitment to keep stimulating the US economy until his target of 6.5 per cent unemployment was clearly within reach, the markets took a very different view: that the Fed was preparing to start reducing its monetary stimulus, perhaps as early as next month.

There was no real evidence for this belief, and indeed Bernanke, along with several influential Fed officials, emphasized the danger of withdrawing stimulus before a strong economic recovery was well established.

Click on NEXT for more...

What's behind the spooked stock market?

Image: Chairman of Soros Fund Managment George Soros.Photographs: Adam Hunger/Reuters

But many investors and media analysts were unconvinced, partly for the reasons of social psychology discussed here last week - and even more important, as the week wore on, by an additional psychological factor.

The very fact that bond markets moved so sharply after Bernanke's comments last week made investors believe his comments must have contained significant new information.

The more prices moved, the more investors became convinced that the market "must know something" about the Fed's intentions, even if this was not apparent from Bernanke's words.

This kind of feedback is an example of what George Soros calls reflexivity - the ability of market expectations to change economic reality, bringing reality into line with expectations, whether the expectations were misguided or justified.

Click on NEXT for more...

What's behind the spooked stock market?

Image: Employees of the Tokyo Stock Exchange work at the bourse.Photographs: Issei Kato/Reuters

Which raises my second question: Is there any reason to believe that monetary stimulus will soon be reduced or withdrawn? There are two broad reasons to doubt this.

First, Bernanke and other Fed officials have repeatedly said they would consider reducing stimulus only if they were confident about the momentum of growth and job creation. To judge such momentum would require at least six months of consistently strong employment figures or two quarters of solid growth in gross domestic product.

Given the erratic statistics published in March and April, it is literally impossible for such a run of strong figures to materialize before the fourth quarter of this year.

Second, Japan and Europe, which have only just gotten out of austerity mode, are certain to continue providing the world economy with more stimulus even after the Fed's monetary expansion begins to subside.

Combining the efforts of US, Japanese and European central bankers, therefore, global monetary conditions are almost certain to become more, rather than less, stimulative for at least another year or so.

It seems, then, that market fears of monetary tightening are almost certainly unjustified, or at least very premature. In which case, should anyone care about the recent stock market and bond gyrations, still less about taking action to calm the markets down?

Click on NEXT for more...

What's behind the spooked stock market?

Image: People walk through the lobby of the London Stock Exchange.Photographs: Suzanne Plunkett/Reuters

Unfortunately, the answer is yes, because of the reflexive interaction between financial markets and economic reality. Although the global economic recovery is becoming stronger, it is still too fragile to withstand a serious financial shock.

If equity prices were to fall sharply or long-term interest rates to rise much further in the next few months, consumer confidence, business investment and housing would all suffer and government deficits would start to widen again.

In short, a financial shock could damage the global economy to the point where deteriorating economic reality would ultimately justify the initial financial shock.

To avoid such a self-fulfilling downward spiral, central bankers and governments in every major economy should make clear that monetary conditions are not about to be tightened.

And they should remind investors that, although a gradual increase in long-term interest rates is a healthy development as the world economy returns to normal, central banks have unlimited monetary firepower when it comes to protecting their economies from excessive interest-rate movements or sudden volatility in financial markets.

Anatole Kaletsky is an award-winning journalist and financial economist who has written since 1976 for The Economist, the Financial Times and The Times of London before joining Reuters. His recent book, "Capitalism 4.0," about the reinvention of global capitalism after the 2008 crisis, was nominated for the BBC's Samuel Johnson Prize, and has been translated into Chinese, Korean, German and Portuguese. Anatole is also chief economist of GaveKal Dragonomics, a Hong Kong-based group that provides investment analysis to 800 investment institutions around the world.

Anatole Kaletsky is a Reuters columnist but his opinions are his own.

article