| « Back to article | Print this article |

Private investment: Engine to drive India's economic growth

By enabling, not colluding, with the private sector, the government can drive growth and deliver social protection on a much larger scale, says Rajiv Lall.

Some of the sheen has undoubtedly come off the Washington consensus around liberal democracies and free markets.* Political gridlock in the US has invited growing commentary about what makes democracies dysfunctional.

And as China's stature in the global economy has grown, voices about the merits of the Beijing model of state-led capitalism with restricted political participation have also become louder.

But whatever the infirmities or inconveniences of democratic forms of government, I believe that it is no longer possible to roll back the momentum of one very powerful global trend.

We may not all agree with Francis Fukuyama's declaration of the The End of History, but it is surely the case that suppressing voice in this information age of digital connectivity is becoming progressively harder.

The democratisation of communication is now a ubiquitous and unstoppable phenomenon. This trend has several important consequences. It is affecting systems of decision-making worldwide. It is this that will continue to drive the demand for greater representation in governance globally.

Even the Chinese Communist Party is not immune to this pressure. The Chinese are well aware of the growing need to accommodate popular opinion. Their genius, if they pull it off, would be to calibrate and control the pace of this transition. Hardly any country (Singapore is the only one that comes to mind) has been able to do this as a matter of conscious strategy.

For the rest of the world, including India, the transition to representative governance has been an unpredictable affair, marred more often than not by violence.

Click NEXT to read more...

Private investment: Engine to drive India's economic growth

As systems of governance democratise, the limits to acceptable levels of social and economic inequity come more sharply into focus. How much inequality is tolerable in any country will vary depending on the societal, political and historical context of each.

But it is inevitable that with greater representation comes greater demand for redistribution and inclusion - political systems must become more responsive to the needs and aspirations of the disadvantaged majority.

Arguably, Americans are more tolerant of disparities in income and wealth than their European counterparts. But even in the US, the logic of electoral politics propelled Roosevelt to launch the New Deal, Johnson to introduce the Great Society, and now Obama to tackle universal health care.

But the US' preoccupation with social safety nets did not start till very late in the country's economic evolution. This is because true political representation in the form of universal suffrage, or one adult one vote, did not come to the US until 1920 when women first got the right to vote.

And it was not until after the Voting Rights Act of 1965, that African Americans, comprising a meaningful share of the adult population, started effectively participating in the country's electoral politics. But by then the US was already a high-income economy with a very large middle class.

The Carnegies, the Rockefellers and other barons had already made their fortunes in the rough and tumble of the country's Gilded Age of the late 19th and early 20th centuries without any unmanageable political opposition from the poor, who were largely prevented from voting through poll taxes and other means.

By the time electoral politics became meaningfully representative, the country was wealthy enough to afford more ambitious social protection. Since then, however, spending on social programmes has grown exponentially and government revenues have not kept pace.

The story is not materially different for other Western democracies, where for the longest time, the representative government was kept only for propertied males, while women and the poor were denied effective voting rights.

In the UK, for example, universal male suffrage was introduced in 1918, and it was not until 1928 that all women gained the right to vote. Only then, after World War II, did the UK fully embrace the welfare state, by which time, as in the US, its per capita income was already quite high.

Click NEXT to read more...

Private investment: Engine to drive India's economic growth

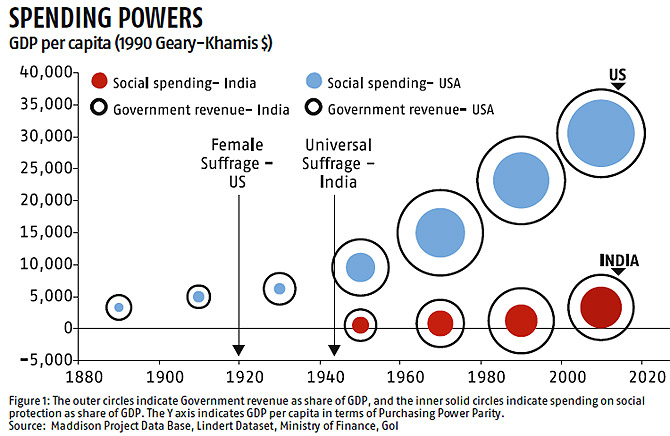

India is truly unique in this respect. We got universal suffrage in 1950 at a much lower level of per capita income than any Western democracy. In no other country have so many poor citizens been given the right to vote at they have been in India.

The result is that our politics is driving us to spend a lot more on social protection at a much lower level of economic maturity than was the case for other democracies. India's per capita gross domestic product (GDP) today is, in purchasing power parity terms, is about the same as the US in 1880.

Yet, its budgetary spending on social protection as a share of GDP is today 15 times larger than what it was for the US in 1880, while its budgetary revenues are only seven times larger.

The implications of this fundamental feature of our political economy are profound. It means that enforcing fiscal discipline in our country is going to remain a chronic challenge.

Any government in this country will struggle to create fiscal space for investment spending. Indeed, government investment spending as a share of GDP has seen a secular decline over the past two decades, irrespective of which party has been in power.

It is no coincidence that the food security Bill got bi-partisan support in Parliament. And no matter who wins the election it is unlikely that the next government will unwind national schemes such as Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act, health insurance for the poor, or mid-day meals very easily.

Rising expenditure on account of schemes to protect minimum consumption levels for the poor today is making it harder for governments to invest even in education and health care, let alone in infrastructure and urban development. But consumption spending by itself cannot drive growth on a sustainable basis.

If a growing share of the government's revenue is, for compelling political reasons, going to have to be allocated towards supporting consumption, the government cannot expect to be an effective driver of economic growth. It follows that India must rely heavily on private investment spending in order to maintain robust economic growth rates.

The scale of the challenge we face is daunting. The government must on the one hand find a way to deliver inclusion and social protection on a much larger scale than has been done anywhere else in the world.

And, given our limited resources, it must do so much more frugally and with much less waste than it has achieved so far. On the other hand, the government must also learn to become an effective champion of private investment activity.

It must enable the private sector, not compete or collude with it. It must build trust, not undermine it, for private investment is the engine that will drive economic growth.

This will take enormous sophistication, skill and discipline on the part not only of our political leadership, but also of our bureaucracy and judiciary. Does the Indian state have the capacity to deliver? Over the next several fortnights I will explore various facets of this challenge.

The author is executive chairman, IDFC.

(This article is based on research that was first presented at a conference in Mumbai in July 2013 in the form of a presentation titled "Democracy, Inclusion and Fiscal discipline.")