| « Back to article | Print this article |

Marwaris feel the heat of Mamata's hostility

The Marwari community has chosen to portray Mamata Banerjee's patent bias against it after the AMRI Hospital fire as unfair persecution.

That is correct, inasmuch as only the Marwari directors of the hospital were arrested and the Bengali ones allowed to remain at large.

But though the crudely selective manner of the AMRI-related arrests is certainly reprehensible, it is also interesting in what it says about the changing nature of links between business and politics in Bengal.

One of the abiding ironies of three decades of Left rule in Bengal is that it provided the platform for an unabashedly capitalist community like the Marwaris to flourish.

Click NEXT to read more...

Marwaris feel the heat of Mamata's hostility

This affinity seems to have covered the entire Left spectrum. Recall, for instance, that no Marwari businessman suffered an attack during the extreme anti-capitalism of the Naxalites in Calcutta (as it was then called) in the sixties.

In contrast, Ulfa and Bodo terrorists made no such distinctions in their extortionary demands in Assam, where the community also has a substantial presence.

Thus, as conglomerates like ITC, Bata, Philips and Lipton and Brooke Bond (before they were subsumed into Lever) started moving their headquarters out of the state as a result of union-instigated labour troubles, Marwari businesses seemed to flourish.

Click NEXT to read more...

Marwaris feel the heat of Mamata's hostility

By the eighties, names like those of the Khaitans, Goenkas, Khemkas, Chitlangias, Kanorias and Kotharis, Lodhas, Ruias and Todis swiftly started building empires.

Much of this occurred on the back of acquisitions of British companies, whose promoters departed India once the Foreign Exchange Regulation Act came into effect, requiring foreign companies to reduce their stakes in Indian subsidiaries.

Familiar corporate names around the central business district - the Magor tea empire, Dunlop, CESC, MacKinnon Mackenzie, Duncans, India Foils, Warren - acquired ownership with roots closer to a north Calcutta locality than the distant shores of London, Manchester or, say, Dundee.

Click NEXT to read more...

Marwaris feel the heat of Mamata's hostility

The remarkable point about this local empire-building was that West Bengal faced a growing number of man-days lost owing to strikes and lockouts, but this community did not appear to suffer a diminution of earning capacity in the same period.

The jute industry, for instance, had become overwhelmingly Marwari-owned by the late seventies.

Mill workers frequently struck work over wages, mill owners declared lockouts just as often and jute farmers suffered terrible deprivations as a result.

This decades-old state of affairs should have attracted the attentions of a party ideologically inclined towards the proletariat, but it never seems to have concerned its representatives in a major way (it is striking that, well into the 21st century, Banerjee is fighting not to have the age-old jute control order diluted to allow industry to use plastic packaging).

Click NEXT to read more...

Marwaris feel the heat of Mamata's hostility

It was not as though the Left Front embraced Marwari capitalism wholeheartedly, but it certainly established a realistic equation with the community.

These links were exemplified by not just a prominent corporate activity but also stronger cultural presence in a city that had rapidly lost its cosmopolitanism as a result of Indira Gandhi's licence raj and the political climate the Left created.

Though many Left stalwarts chose to play down such associations, then chief minister Jyoti Basu, who built his political career on trade unionism, suffered no such qualms.

He openly socialised with them and, in some cases, intervened when labour disputes threatened their businesses.

Click NEXT to read more...

Marwaris feel the heat of Mamata's hostility

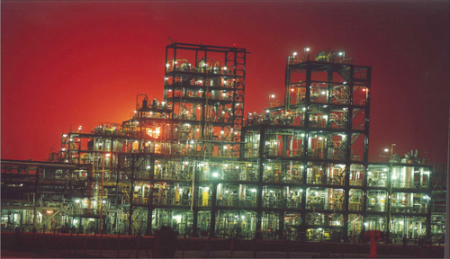

When Basu's showcase project Haldia Petrochemicals was in trouble in the late eighties, it was to the Grey Eminence of the community, Rama Prasad Goenka, to whom he turned (though Goenka, too, eventually exited a project that has suffered an eternal saga of controversy).

By the early nineties, when the Left painfully concluded that foreign and private investment could stoke growth, the in-joke was that the M in CPI (M) stood for Marwari.

This was slightly unfair since the Left Front's wilfully destructive policies through the eighties prompted younger generations of Marwaris to exit the state as well.

Click NEXT to read more...

Marwaris feel the heat of Mamata's hostility

The Mittals of Ispat and Kanorias of Kanoria Chemicals and gen-next of the Birla clan all literally took their business elsewhere, even as Buddhadeb Bhattacharya's attempts to fill the gap with foreign investors proved a signal failure.

Banerjee's entry on the political scene has destabilised the old equations - not least because she won on a staunchly anti-capitalist platform.

With Tata's Nano project relocated to Gujarat, the Nandigram chemical complex a non-starter owing to her strongly organised opposition, several businessmen who had put their faith in the reforming Left - Videocon, JSW among them - are prudently retreating now.

Banerjee's Manichaean brand of politics means that she remains implacably hostile to the Left, so the Marwari community is likely to suffer by association.

That's the essential message from the AMRI tragedy now - and it is worth watching which side draws what lessons from it.