| « Back to article | Print this article |

Is the Modi miracle overrated?

On an important governance measure, there is a Nitish Kumar effect, a Naveen Patnaik effect, but no Modi effect, says Arvind Subramanian.

Robert Solow, the Nobel Prize-winning economist, once quipped that one could see the computer age everywhere "except in the productivity statistics".

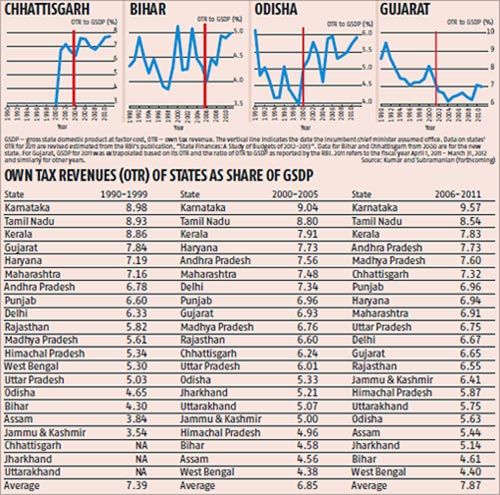

Narendra Modi's much-touted Gujarat governance miracle (2002 apart, of course) raises a similar puzzle, which can be posed as follows: in the tax collection data, why can one see a Raman Singh effect, a Nitish Kumar effect, a Naveen Patnaik effect, but not a Narendra Modi effect?

In ongoing research with Utsav Kumar of the Asian Development Bank, we look at one dimension of governance, namely the ability to raise taxes. Historically, institutional development has been associated with effective taxation.

Taxation is the glue that binds the rulers and the ruled: the fact that they are taxed gives citizens an incentive to hold rulers accountable, and this in turn helps to ensure that the latter deliver value for money by way of efficient services to citizens.

Click NEXT to read more...

Is the Modi miracle overrated?

"No representation without taxation" is, thus, one of the key insights of political and economic development. A corollary is that reasonable (but not onerous) taxation ensures that good governance will be durable, outlasting individual leaders.

How do the different states fare on this measure, which we compute as the revenues generated by each state (own tax revenues, OTR for short) as a share of its gross domestic product? Before examining the puzzle, this measure needs to pass a smell test.

We know, for example, that Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and Andhra Pradesh are the relatively better performing and governed states in India.

The table provides corroboration. These states have high and stable, or high and rising, ratios of OTR to GDP. In the last five years, for example, these states have on average raised the maximum amount of revenue (eight to 10 per cent of GDP) and this ratio has risen over time, by about one percentage point relative to the 1990s.

Click NEXT to read more...

Is the Modi miracle overrated?

A different smell test relates to the laggards. Here again, we find, unsurprisingly, that West Bengal brings up the pack. It has one of the lowest levels of OTR to GDP in recent years (4.4 per cent) and this ratio has declined consistently since the early 1990s.

As Devesh Kapur argued recently ("The Tea Party state", January 14, ) the Marxist state that believes in the power of government to affect lives has been shambolically ineffective in acquiring the resources to do its job.

Next, Charts 1-3 plot the OTR-to-GDP ratio for those states whose chief ministers – listed above – have in recent years acquired a reputation for effective governance (the vertical line indicates the date they came into power).

Again, it is striking that for all these cases – Chhattisgarh, Bihar and Odisha – tax collection improves after they assume office and by an amount that is roughly equal to that posted by the traditionally well-governed states (tax collections have also improved under Shivraj Singh Chauhan in Madhya Pradesh).

Click NEXT to read more...

Is the Modi miracle overrated?

What about Gujarat? The table illustrates that during the Modi era, Gujarat ranked among the poor performers in the level of tax collection (rank of 12 among the 21 large states covered by our analysis; see table).

More striking is the fact that this collection effort has declined since the 1990s, by about 1.2 percentage points (chart 4). This decline is actually dramatic - because this was a period during which Gujarat grew very rapidly, which should have elevated its tax collections.

On this important measure of governance, Mr Modi stands indicted as a mediocre performer and one whose performance has not improved over time.

Moreover, it could be argued that low tax collections do not just augur badly for Gujarat's future institutional development, they might also be partly responsible for Gujarat's less-than-stellar performance on social outcomes (as Bibek Debroy and Mihir Sharma have argued).

Click NEXT to read more...

Is the Modi miracle overrated?

Recall that Gujarat for its level of per capita GDP had low life expectancy and high child malnutrition, which I wrote about earlier (Business Standard, July 25, 2012). Gujarat's expenditure as a share of its GDP is the third lowest amongst the 21 large states.

But this might be a very misleading, even unfair, assessment. A number of counter-arguments could fully or partially restore Mr Modi's reputation for good governance.

First, Mr Modi could argue – consistent with his right-of-centre ideology – that far from being condemned, he should be celebrated for delivering dream outcomes. He reduced the size of government and did so by delivering faster growth and better services than anywhere else in the country.

And all this while relying very little on transfers from the Centre and maintaining low deficits (Gujarat, however, is a median, not stellar, performer on this measure). In essence, this would amount to dismissing the metric of performance that is used here.

Click NEXT to read more...

Is the Modi miracle overrated?

A second defence is related to the above, but is subtly different. Mr Modi could concede that declining tax collection is a source of worry, especially for Gujarat's ability to sustain good service delivery in the future.

But he could insist that lowering taxes and granting incentives were the price he had to pay for luring private investors and facilitating faster growth.

Moreover, in India, where the competition-between-states dynamic has been unleashed, such a strategy is unavoidable. I have just been better at this game than anyone else, he could legitimately claim.

Click NEXT to read more...

Is the Modi miracle overrated?

In terms of economic governance, is Mr Modi Gujarat's greatest gift after Mahatma Gandhi and Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, as Anil Ambani recently gushed?

Is he merely a good but not Great Leader? Or, is there an underside to Mr Modi's Gujarat governance miracle that might only become evident in the future as the tax metric discussed here suggests?

Even if time will tell, it is unlikely to tell in time for voters to make informed choices - choices that will determine whether Mr Modi will be allowed to do for India tomorrow what he has done (or not done) for Gujarat this last decade. <hr>

The writer is Senior Fellow, Peterson Institute for International Economics and Centre for Global Development.