| « Back to article | Print this article |

Inflation targeting: What are banks, market fretting about?

Whether inflation targeting makes sense if core consumer price inflation doesn’t respond to the interest rate, wonders Abheek Barua.

Since the April monetary policy is drawing near, I thought I would add my two bits to the debate on inflation targeting that the money markets and banks are fretting about so much.

Like the cliched “motherhood and apple pie”, targeting inflation has to be fundamentally a good thing. All arguments against the new inflation targeting regime that the Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI’s) expert committee has proposed could end there. But that’s not quite the point.

An assessment will have to focus on the potential costs of the approach and its likely efficacy in bringing inflation (consumer price inflation under the new regime) down.

The extreme argument is that it does damn all to bring down inflation — but imposes crippling costs on the economy in the form of, say, slower growth and high loan delinquency. Where does one stand on this?

My problem with the inflation targeting model that the RBI is likely to follow is that, despite RBI Governor Raghuram Rajan’s best efforts, there are lingering misconceptions about how it works.

Some sections of the financial markets seem to go by what could best be described as a caricature of inflation targeting and are drawing some extreme conclusions.

Perhaps they haven’t read Dr Rajan’s speeches carefully enough! I come across a number of market-wallahs who believe that inflation targeting is some sort of binding rule that forces the RBI to hike rates as long as the consumer price index (CPI) remains above the target level.

Given the somewhat recalcitrant CPI rate, that would imply a series of quick rate hikes going forward.

Click NEXT to read more...

Inflation targeting: What are banks, market fretting about?

A few things need to be emphasised here. First, the RBI describes its approach as flexible inflation targeting and that itself suggests a degree of discretion.

Second, if one wants to be pedantic about these things, inflation targeting in general is far from being a “rule” in the theoretical sense. It actually allows considerable flexibility to a central bank to use a variety of instruments – exchange rates, money supply, short-term liquidity – in bringing inflation down to the target level.

Of course, all this would impinge on interest rates; but it’s far from being the mechanical mapping from inflation prints to policy rates that some people make it out to be.

Ben Bernanke quite aptly described it as “constrained discretion”. A monetary rule, on the other hand, would say: set a fixed rate of growth of money supply and stick to it come what may.

Also, while the data on inflation do influence rate decisions under inflation targeting, it is really the RBI’s forecast of the evolving path of inflation that guides policy decisions.

Thus, despite a relatively high current inflation or a spike in the rate, the RBI might refrain from touching rates if it believes that the rate is headed down. (I would, however, rule out a cut in interest rates at this stage, despite the softening CPI numbers and persistently dismal industrial growth prints.)

One implication of this flexibility is that inflation targeting is not de facto a kind of shock therapy that the RBI wants to administer.

Despite the frenzied clamour from some of our home-grown hawks that the RBI “do a Volcker” and try to bring down inflation quickly, Dr Rajan has rejected the idea of going in for a series of quick interest rate hikes.

In his defence, he has cited the recession that Paul Volcker’s therapy set off and the period of financial instability that built up to the infamous savings and loan crisis.

Mr Volcker’s cheerleaders in India should also try to understand the context in which Mr Volcker used therapy — especially the prolonged monetary profligacy that was associated with his predecessor Arthur Burns.

Click NEXT to read more....

Inflation targeting: What are banks, market fretting about?

I don’t think anyone at the RBI or on the expert committee seriously believes that food prices can be tamed through purely monetary instruments.

However, a simple plot of food prices, rural wages and urban wages suggests a nexus between them. I use the word nexus consciously because the graphs do not suggest a uniform direction of causality.

However, the fact that the rise in food prices does seem to be associated with higher rural and urban wages means that it could ultimately manifest in more generalised inflation.

Monetary policy certainly has a role in preventing this, and an interest rate response to a sustained increase in food prices need not seem that irrational after all when viewed from this perspective.

So far, so good. However, I have a few questions about flexible inflation targeting, or inflation targeting in general, that need to be answered before giving it an enthusiastic thumbs up.

To start with, I have some sympathy for the argument that the degree of household exposure to the financial system or simply their leverage is critical to the success of this model.

Click NEXT to read more...

Inflation targeting: What are banks, market fretting about?

After all, if inflation targeting were to use interest rates or monetary policy to check inflationary expectations, households need to be exposed to the interest cycle to begin with.

The low level of household leverage in India, as well as the steady level of inflation expectations over the last couple of years, seems to suggest that interest rates are somewhat ineffective in influencing inflation expectations.

The counter to this is the apparent success of inflation targeting in economies like Brazil where household borrowing levels relative to gross domestic product were just a tad higher than those in India.

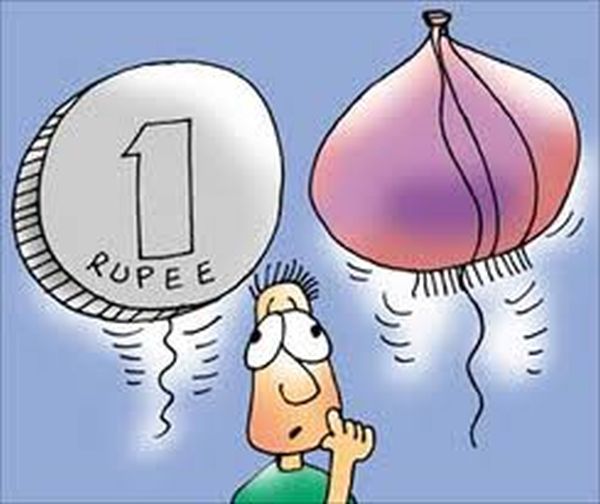

The biggest fear about both the choice of the CPI as the target and flexible inflation targeting is the visible lack of sensitivity of a number of components of the core CPI (stripped of food and fuel) to changes in the interest rate. This is particularly true of services like housing, as well as health care, transportation and so on, which constitute the “miscellaneous” category of the CPI basket.

The insensitivity of the “core CPI” to interest rate increases stands in stark contrast to the core wholesale price index (WPI) inflation that has dropped sharply at least partly in response to rising interest rates.

Click NEXT to read more

Inflation targeting: What are banks, market fretting about?

I would argue that the sources of the stickiness in some of the key components of core CPI need to be investigated and understood before attempting to broadside headline CPI with the flexible inflation- targeting strategy.

While the target of eight per cent for CPI inflation by the end of 2015 might seem within reach, the journey from eight to six per cent (the target for end-2016) seems somewhat difficult.

Thus, there is a risk that the central bank will either miss the target altogether or lose credibility.

The second, and equally disruptive, option is that in a desperate bid to willy-nilly bring inflation down, it might ultimately resort to doing a Volcker. Setting specific targets unfortunately comes with the unavoidable risk of missing them.

Inflation targeting: What are banks, market fretting about?

pp