| « Back to article | Print this article |

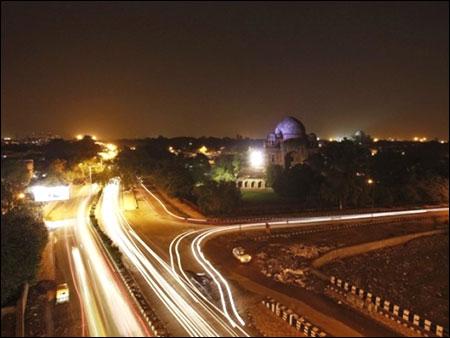

India is a real market for power

Open access for consumers of electricity and a more effective market exchange for power are necessary.

In the wake of the July 31 blackout, much has been said and written about the policy failures in the power sector. The litany of woes is a long one - inefficient state electricity boards (SEBs), their huge accumulated losses, power thefts, problems with coal linkages, uneconomic consumer tariffs, capacity kept idle despite shortages, and so on.

Let me give a broader structural explanation: we have failed because we relied on private investments without creating an effective market-based system for power trading.

Historically, the power system in India, as in other countries, has evolved on the basis of vertically integrated utilities that function as monopoly producers and retailers of electricity in specific geographies within the country.

This has changed radically in recent years in many countries, where the vertically integrated utilities have been dismantled, entry into power generation opened up, distribution made competitive not just for markets - by a bidding process for licences, as in India - but within markets, by allowing consumers to choose the retailer from whom they can buy power.

Click on NEXT for more...

India is a real market for power

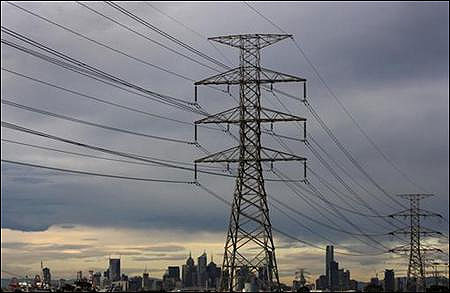

There are, however, two features of the market for power that need to be recognised. First, the power system requires an instantaneous balancing of supply and demand since, for all practical purposes, "inventories" of power cannot be held to meet temporary shortages or surpluses.

Second, the power system is interconnected in a manner that imposes some technical requirements for system stability that cannot be left to the free interplay of bilateral trading deals. That is why even a market-based system needs a system co-ordinator independent of the generating companies (gencoms) and distribution companies (discoms).

A key issue is the relationship between the system co-ordinator and the entity that runs the market exchange. The latter operates in a manner very similar to other market exchanges. The day ahead market operates with gencoms and discoms indicating their offers and bids for specified quantities of power for a defined time intervals, typically 15-minute intervals spread through the day.

The market exchange works out the market-clearing price, and that is the rate at which payment is made by a discom buyer to the gencom seller. Similar arrangements hold for longer-term trades up to a year in advance.

Click on NEXT for more...

India is a real market for power

The link with the system co-ordinator is necessary because only it can establish that the delivery of the contracted amount of power by gencom A at point X in the grid and the withdrawal of the contracted amount (minus any provision for transmission loss) by discom B at point Y in the grid is consistent with system stability, given all the other bilateral transactions that have to be accommodated.

Therefore, it makes sense to keep the transmission system independent of the gencoms and discoms and make the same entity the system co-ordinator and the manager of the market exchange.

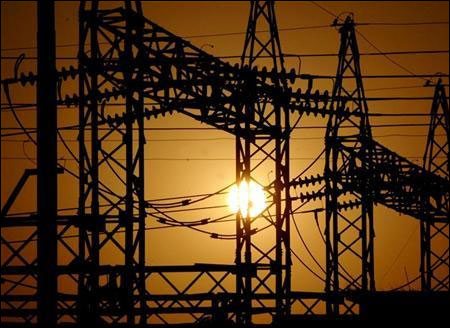

How far are we on this road in India? We have certainly opened up the generation and distribution sector to private players. In 2003, a new Electricity Act was enacted that held out the promise of a market-based power system with a clear separation between generating companies, distribution companies and the transmission system.

A system of competitive bidding was established to replace the old discredited memorandum of understanding (MOU) system for new gencoms.

A separate power exchange for trading was set up. An effort was also made to clean the books by funding the accumulated losses of the SEBs, and fairly large sums were poured into schemes to modernise the system. But actual performance falls well short of promise.

Click on NEXT for more...

India is a real market for power

As far as the separation is concerned, the Shunglu panel on SEB losses observed that "the unbundling of SEBs ... is more in form and not sufficiently in substance". One measure of this is the fact that "short-term trades" (defined as trades that are less than one year forward) amount to just about 11 per cent of generation.

We have privatised ownership, but in every other respect the power system is not very different from the old vertically integrated monopoly and the new private gencoms are hostage to the SEBs.

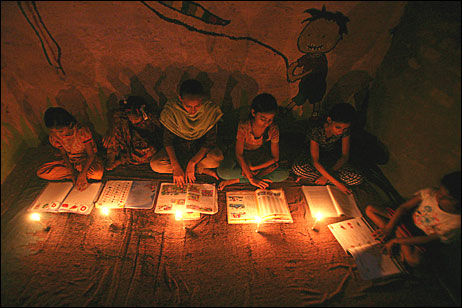

The effort to clean up the books of the SEBs came to nought as tariff adjustments were avoided on political grounds and the real price of electricity has fallen by 25 per cent relative to the all commodities index since 2004-05.

Margins came under pressure since, by 2011-12, electricity prices were 15 per cent higher than in 2004-05; while the price of the dominant primary energy source, non-coking coal, went up by 80 per cent. It is hardly surprising that the accumulated losses of the SEBs have now reached a level close to three per cent of GDP.

Click on NEXT for more...

India is a real market for power

The Electricity Act includes a provision for open access. The power ministry has recently confirmed the right of any consumer with a load above 1 Mw to access power from any source without the regulatory authority exercising any jurisdiction over price.

But in practice the transmission system is not truly independent of the SEBs that ensure open access is in effect denied to private suppliers and buyers.

The reform of the power sector must begin by correcting this, so that a competitive power market emerges. Entry into generation should be eased particularly for small players, which would help greatly in promoting wind and solar power.

Direct links between gencoms and big customers should be permitted. Privately owned local grids should be encouraged, particularly in remote and rural areas. Discoms should be encouraged to go for smart grids and time-of-day charges. System co-ordination and the management of the market exchange must be integrated.

Click on NEXT for more...

India is a real market for power

It could be argued that discoms with a local monopoly may need to be regulated to protect consumer interests.

But if the distribution system is also unbundled with the wires being run by an independent or co-operative entity, then it is possible to give even small consumers a choice of suppliers and rely on competition rather than regulation to protect consumers. In rural areas, the answer may lie in electricity co-operatives.

The biggest barrier to this change is the culture of the institutions that run the power system. Engineers will have to be convinced that matters like system stability and reliability will not be compromised by market forces.

Free-market fundamentalists will have to accept the need for some central co-ordination of trades. But without this deregulation of pricing and structural redesign, the power system will continue to be a drag on development.