| « Back to article | Print this article |

If Indian companies don't spend on R&D, they will die

At present, India spends 0.9 per cent of its GDP on research and development (R&D), which is well below what developed countries, says Nitin Desai.

Sustaining high growth will require three things: continued outward orientation so that we do not slip into stagnation behind protective walls; promoting a competitive environment locally so that successful companies outpace laggards; and technological dynamism.

The technology factor is perhaps the most important, since it underlies the other two. Maintaining outward orientation requires both productivity improvements and innovation, which is directly connected to technological capacity.

Also, technology matters for maintaining a competitive environment. Firms must move from competing for regulatory leverage (which is still the case, despite liberalisation) to competing for markets and capital market presence - and that depends on a firm’s perceived technological capacity.

Click NEXT to read more...

If Indian companies don't spend on R&D, they will die

Indian industry has done well in terms of reverse engineering, cost-cutting and efficient project implementation.

But as we look to 2050, this will not be enough. An industrial sector that is 20 to 30 times larger than the one at present will be one of the biggest in the world, and it cannot count on easy access to foreign technology.

More than that, its presence in global markets will require innovation that goes beyond cost-cutting, as it progresses to middle-income status and beyond.

One must also recognise that a growing Indian market will require locally relevant products, processes and business models.

Innovation gives firms a first-mover advantage that can create new markets at home and abroad.

Click NEXT to read more...

If Indian companies don't spend on R&D, they will die

One saw this in the role that innovation in consumer electronics and fuel-efficient cars played in Japan's high-growth phase. The spin-off effects of major innovations on the wider economy can run deep.

A classic example is the role of internet innovations in creating hundreds of thousands of new jobs - initially in the United States, and later the world over. A more diffuse impact can come from the boost to overall growth because of faster productivity gains.

The big question is how this transition from imitation-driven industrialisation to innovation-based industrialisation can be fostered.

At present, India spends 0.9 per cent of its GDP on research and development (R&D), which is well below what developed countries – even China – spend.

In absolute terms, our expenditure on R&D is about a fourth of what China spends.

Click NEXT to read more...

If Indian companies don't spend on R&D, they will die

The government accounts for about two-thirds of this expenditure, while the private sector spends the rest.

If one looks at the list of the 1,500 corporations that account for some 90 per cent of global R &D expenditure, only 15 Indian companies figure in the list — the highest-ranking one, Infosys, is placed at 330.

About half of those 15 companies are pharmaceutical firms and only two are from the public sector.

This has to change. With the sort of commitment that the government is now showing, the challenge is not funds for publicly financed R&D; it is to broaden and widen the private sector commitment, forge closer links between science and technology policy and industrial policy, and address human resource needs.

Many foreign companies have set up R&D facilities here partly because of the generous incentives and partly because of the lower cost of personnel.

Click NEXT to read more...

If Indian companies don't spend on R&D, they will die

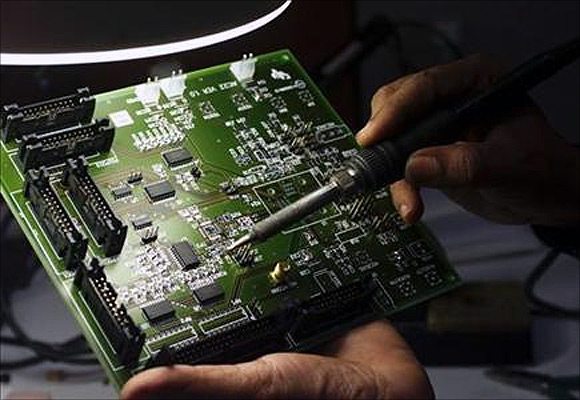

Indian companies have shown some interest in expanding their R&D presence lately - this can be seen in the acquisition of foreign companies that provide access to R&D.

For instance, the acquisition of Corus gave the Tatas the rights to 80 patents and about 1,000 researchers. But inorganic growth is not enough; organic growth in corporate R&D is necessary.

Competitive pressures will increase the pressure to invest in R&D. But something more than relying on the natural evolution from imitation to innovation will be required.

The main instrument we use at present for stimulating R&D in the private sector is the tax incentive.

The economic case for this is that study after study has shown that the social returns to R&D, mainly on account of the spillover effects, are much larger than the private returns - and a tax subsidy helps close the gap.

Click NEXT to read more...

If Indian companies don't spend on R&D, they will die

The present incentive is the most generous in the world, allowing a 200 per cent write-off of current expenses and equipment costs from the year’s profits.

There is no case for increasing this. However, some tweaking to make it more directed may be useful - for instance, linking the incentive not just to the level but also to the growth in R&D spending.

One instrument that can be used is the public procurement programme, defence purchases in particular.

Click NEXT to read more...

If Indian companies don't spend on R&D, they will die

For this the defence services will have to recognise that sometimes the “immediate threat” argument for imports must give way to the need to build an indigenous defence industry.

No country has become a great power on the strength of imported arms. The move towards developing an indigenous defence industry in the public and private sectors has started; but much more needs to be done to push it further.

The government spends a fortune supporting publicly funded R&D in Council for Scientific and Industrial Research institutes, science and technology institutes and elsewhere.

Click NEXT to read more...

If Indian companies don't spend on R&D, they will die

We must connect these research institutions with industrial research by setting up a commercial arm in each one to mobilise industrial support for institutional R&D; packaging consultancy services of research staff to provide services to industry; incubating start-ups by research staff; and commercialising in-house technology developments.

Innovation is as likely to come from small start-ups as from large corporations.

We need an ecosystem for venture capital to bring together technologists, entrepreneurs and early-stage investors in order to provide a funding window for start-ups that experiment with new products, processes and business models.

A deeper capital market with private equity players and low-cost listing for small companies will help.

Click NEXT to read more...

If Indian companies don't spend on R&D, they will die

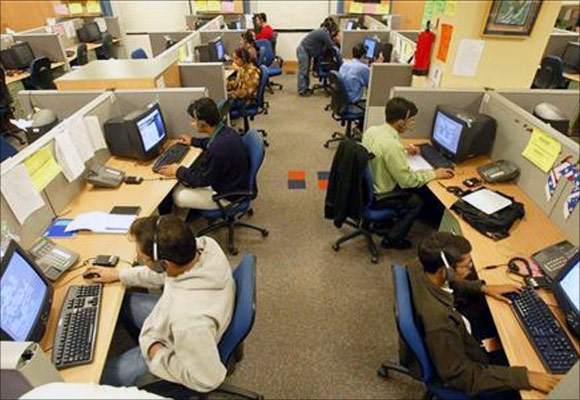

Finally, we need to make research jobs more attractive to postgraduate students. Today, some 75 per cent of engineering graduates end up doing low-skilled work in the information technology sector.

An expansion in corporate interest in R&D investment will help correct this to some extent.

But the government also needs to do much more to improve the quality of science and technology education.

Our corporations must recognise that they have, at best, a decade before their access to foreign technology on the cheap dries up. If they have not established their own R&D capacities at home, they will perish.