Photographs: Uttam Ghosh/Rediff.com Ajit Balakrishnan

As Indian democracy deepens, power shifts will continue to happen and the middle class needs to accept that all such power shifts may not be in their favour, says Ajit Balakrishnan.

Nowadays, I find my mind turning to memories of a granduncle. He was over six feet tall, had a booming voice and, by the time I was ten, was already in his 70s and retired from the British Raj government as a head constable of police.

He went for his evening walk carrying a lathi-like stick and had an imposing presence; I could imagine him quelling prospective independence 'agitators' with just a look in their direction.

Of an evening he would turn into our gate, seat himself on our verandah, take a sip of tea, lean back on his chair and declare, "This country is so corrupt! It is going to the dogs!"

This was usually followed by a passionate recounting of the latest misdemeanour in the municipal corporation of Cannanore, that little town in Kerala where I grew up. My mother, who no doubt had heard this diatribe before, would continue knitting scarcely offering a comment.

You can see why my mind, nowadays, wanders to thoughts of my early childhood and of my retired granduncle. Judges, ministers, Members of Parliament, civil servants, businessmen, NGOs, investigative agencies, sports bodies, media personalities, all hurl accusations of corruption at each other.

Everyone seems to be saying what my granduncle used to tell us fifty years ago: "This country is so corrupt; it is going to the dogs!"

Maybe it is time we turn to Mark Granovetter, the Stanford University sociologist, who in his book, The Social Construction of Corruption, points out that cries of corruption often hide power struggles and that groups with conflicting interests will present standards that label their own behaviour as appropriate and label behaviour that benefits competing groups as illegitimate or 'corrupt'.

. . .

Decoding India's corruption wars

Photographs: Uttam Ghosh/Rediff.com

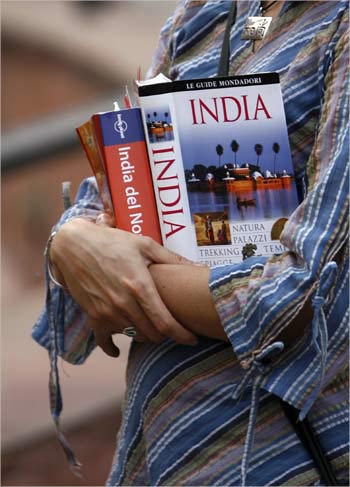

One such social group, that is in the thick of today's corruption wars and labelling exercises, is one that Leela Fernandez of the University of Minnesota calls the New Middle Class.

This group, she says, in her book, India's New Middle Class, Democratic Politics in an Era of Economic Reform is not merely defined by income or occupation or even caste. It descends from the groups in India that embraced English-language education and found employment in the colonial state in the modern professions such as medicine, law, the military and the civil service and has dominated Indian public life because of the cultural capital it possesses.

This cultural capital is then maintained by their privileged access to the few good quality English medium schools that exist in India today and as a consequence to those few high quality higher education institutions that act as gatekeepers to jobs in the higher civil service, in public and private sector management, and professional jobs in the media, financial services, law, medicine and teaching.

This cosy arrangement is being threatened, starting from the mid-1960s, as democracy in India deepens.

The Congress party, from its founding in 1885 till well into the Independence era, maintained its power by enlisting a combination of the English-educated middle class and well-to-do landowners.

The English-educated middle class through their cultural capital maintained a monopoly of the civic discourse and controlled the definition of the public interest and the land-owners brought with them the control of the patron networks they commanded in rural India as described by Lloyd and Suzanne Rudolph in their 1967 book, The Modernity of Tradition.

The first blow was struck when social reform movements in the South in the 1920s dismantled the vertical structure the landowners controlled.

. . .

Decoding India's corruption wars

Photographs: Reuters

The rise of the Dravida Munnetra Kazhagam in Tamil Nadu and the Communist Party of India in Kerala was early example where small peasant and artisan groups adopted English education and learnt how to compete for political office.

The next blow was struck when land reforms in the 1960s broke up large estates all over India. Small peasants and artisans, who were the beneficiaries of this land reform, quickly acquired the economic capital first and then learnt to use their numbers in the electoral lists to convert this to political capital.

Marguerite Robinson's Local Politics, the Law of the Fishes describes this for Andhra Pradesh; Oliver Mendelsohn's The Transformation of Authority in Rural India describes this for Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Rajasthan; and Jan Bremen's Footloose Labour, for Gujarat.

Lucia Michelutti of the London School of Economics sees this as a deepening of Indian democracy. 'New idioms about respectability and authority are developing on the ground,' she says in her 2008 book, The Vernacularisation of Indian Democracy.

In her interviews in Mathura, UP, many respondents expressed admiration for leaders with a 'goonda look': a strong muscular physique, a leather jacket even in 45 degree Celsius heat, sunglasses, a powerful motorbike, all used to convey a cool, successful image and says that such 'goonda qualities and skills are considered attractive characteristics and almost a necessity for a leader who operates in contemporary urban North India'.

She describes how poverty, illiteracy, a disregard for law and order, and political violence co-exist with a commitment to the idea of democracy among the poor in North India. Democracy has been vernacularised!

The New Middle Class has retaliated by waging a subtle war to label elected representatives and politicians as corrupt. The battleground for this war is the English-language print and TV media which reach a miniscule 25 million people in India, while the vast Indian language print media with 170 million readers and the Indian language television with 300 million viewers remain largely unconcerned.

. . .

Decoding India's corruption wars

Photographs: Reuters

However, this tiny English-language media audience supports, nearly Rs 10,000 crore (Rs 100 billion), or 50 per cent of all advertising revenue. Winning the hearts and minds of this audience is crucial for media owners.

NGOs, the praetorian guard of the New Middle Class, are at the forefront of such labelling exercises.

The current NGO demand for a Lok Pal, uses the corruption platform, but its real goal is to give the New Middle Class leverage over elected representatives of the people.

In an earlier move, NGOs pressurised the Election Commission to require candidates for electoral office to file affidavits listing 'criminal charges' against them. Most 'charges' are for things like 'unlawful assembly' but this move has not only created an incentive in the rough and tumble Indian electoral scene for political rivals to trump up 'charges' against each other but also label politicians as criminal and corrupt.

This is unfair because a person is innocent unless proven guilty. Affidavits ought to be necessary only if charges against a candidate have been proven in court.

Much of the discourse about corruption in modern India is framed by the work of the Santhanam Commission of the early 1960s and two key institutions that we have today for preventing and investigating corruption -- the Central Vigilance Commission, and the Central Bureau of Investigation -- were created based on this Commission's recommendation.

'Corruption can exist only if there is someone willing to corrupt and capable of corrupting,' said Santhanam. 'We regret to say that both this willingness and capacity to corrupt is found in a large measure in the industrial and commercial classes.'

. . .

Decoding India's corruption wars

Photographs: Uttam Ghosh/Rediff.com

For Santhanam, the villains were the 'industrial and commercial classes' from who the newly created public enterprises had to be protected.

This is the reason why it proposed a Central Vigilance Commission supervising an army of vigilance officers posted in all public and quasi-public undertakings.

It also proposed a Central Bureau of Investigation to look into such cases. All of the prejudices and hopes of 1960s India are embedded in these words of the Santhanam Commission demonising 'the industrial and commercial classes' and in the architecture of the recommendations.

It is no surprise then that the Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry -- FICCI -- refused to provide testimony before the Santhanam Commission.

FICCI represented, after all, the very 'industrial and commercial classes' that the Commission inveighed against.

The Santhanam Commission constructed corruption as essentially arising from the depredations of the 'industrial and commercial classes'. The modus operandi of these classes, it felt, was one of subverting the working of the newly created State enterprises.

Viewing the same issues in today's light we are more likely to attribute this form of corruption as arising from the License Raj and excessive domination of the economy by the State. We may merely propose that the License Raj be abolished.

. . .

Decoding India's corruption wars

The Committee added two more elements to its construction of corruption that haunt us to this day.

The first element was how the term 'public servant' was defined. The Indian definition is very different from the definition in advanced industrial economies. In those economies, 'public servants' are only those civil servants who are directly employed by the State.

In India, it was defined very widely and includes 'any person required to perform a public duty' and 'public duty' is defined equally broadly: essentially any duty that 'the public at large has an interest in'.

This includes obvious government functionaries like ministers of the central and state governments and bureaucrats and sarpanches in villages.

It also includes judges in courts, employees of nationalised banks and insurance companies, officers of railways and state transport corporations, teachers in schools and colleges that accept any modicum of government financial support.

This wide definition today includes possibly 25 million people, making the task of vigilance and anti-corruption immense.

The second element was that it has constructed corruption as a criminal offence instead of a combination of criminal and civil offences.

. . .

Decoding India's corruption wars

Photographs: Reuters

Criminal offences are much more difficult to prove in court because the standards of proof for them are much higher. For example, to secure a criminal conviction for corruption, investigators have to actually trap public servants in the act of receiving money.

On top of this, Indian courts, consistent with our view of a democratic polity, have prescribed elaborate safeguards for 'trapping' public servants in the act of receiving bribes. The end result, because of these and related reasons, is that corruption charges take years, if ever, to be proven.

And even if criminal charges are proven, there is no easy way to make a corrupt public servant give up the fruits of his ill-gotten gains because the current Indian law makes it difficult to attach property that is bought with proceeds of a corrupt act and held in the names of close relatives, (so-called 'benami' transactions).

One of the foremost 'labellers' of corruption in our time is Transparency International. This Berlin-based non-governmental organisation publishes a widely followed annual ranking of countries that it calls The Corruption Perception Index.

The 2010 edition puts Denmark at the top, i.e., the least corrupt country in the world and puts Somalia at the bottom of the 178 countries ranked, as the most corrupt country in the world.

India is at 87, roughly in the middle, behind our sibling rival, China, at 78. Mexico is at 98, behind us and so is Argentina at 105.

The higher echelons of the list are usually occupied by small European countries like Denmark, Finland, Sweden and the Netherlands, and by small island nations like Hong Kong and Singapore.

. . .

Decoding India's corruption wars

Germany, at 15, leads the larger nations ahead of the United Kingdom at 20 and the United States at 22.

Egypt, where the ruling Mubarak clan has been recently driven out of office amidst allegations of massive corruption, is at about the same level as India.

Switzerland, a country that is usually implicated in most corruption scandals is at a lofty 8th rank, raising the first eyebrow about what exactly is being measured by this index.

Transparency International's index, is in essence, an opinion poll of mostly Western businessmen though, in recent years, respondents in target countries have also been included.

Respondents are asked questions, such as 'Do you trust the government?' and 'Is corruption a big problem in your country?' -- questions which sound perfectly fine, until we realise that the word 'corruption' packs into itself a wide range of meanings and feelings of dissatisfaction which may have little to do with financial wrongdoing per se.

The origin of Transparency International and much of the international brouhaha about corruption harks back to the Watergate scandals of the mid-1970s in the United States.

Congressional investigators, tracing the flow of illegal campaign contributions, stumbled on the fact that as many as 400 American companies had resorted to a range of questionable payments, including bribery of high foreign officials, making 'facilitating payments' to them and even payments to get favourable tax treatment.

. . .

Decoding India's corruption wars

Photographs: Reuters

In the climate of moral outrage of that time, the US Congress enacted, in 1977, the Foreign Corrupt Practices Act prescribing strict criminal and financial penalties for such actions by US companies.

This remained the only law trying to deal with transnational corruption till US companies began protesting that this law put US companies at a competitive disadvantage against their European competitors who were not only free to pay bribes to foreign officials but could also claim income tax deductions for such payments!

Intense pressure from US exporters led the OECD, a group of advanced economic countries, to adopt similar legislation criminalising the bribery of foreign officials and removing tax deductions of these bribes.

Transparency International was born out of these events. US AID was a generous early financier for the organisation and during the period of intense lobbying by US firms to get OECD to adopt and ratify the anti-corruption convention, contributed a fourth of TI's budget.

According to Julie Bajollee of the French Corruption Research Network, Shell, the giant British oil company was another early financier and supported both the TI's international secretariat in Berlin as well as its chapters in Bangladesh and Columbia and so have KPMG and PriceWaterhouse, the big international accounting firms financed many country chapters.

The CBI is frequently drawn into these battles but, as we have pointed out, imperfections in Indian anti-corruption laws make it difficult for the CBI to convict even 10 per cent of the people they bring charges against.

The CBI tries to compensate for this by staging photo-ops that show them escorting away prominent personalities misleading the public and labelling the people being led away as already guilty of corruption, whereas what the CBI is doing is only seeking information about a possible crime.

. . .

Decoding India's corruption wars

Photographs: Uttam Ghosh/Rediff.com

The CBI and the media must be mandated to refer to all such people not as 'accused' but merely as 'persons of interest', as they increasingly do in the United States.

The judiciary is invoked from time to time by all combatants to referee their disputes but as Madhav Godbole, a former home secretary, points out in his recent book, The Judiciary and Governance in India, there are 16 million criminal cases pending in court and proposals for speeding things up such as increasing the number of working days in high courts from the present 210 per year to 260 are opposed by Bar Associations.

As democracy deepens, dramatic power shifts will continue to happen in the Indian society and the Middle Class needs to accept that all such power shifts may not be in their favour.

The Indian Middle Class sowed the wind of democracy and is now reaping its whirlwind.

On a recent visit to Cannanore, that little town in Kerala where I was born, I strolled down one morning to the stretch of sand by the sea where tombstones of the town's grandees stand cheek by jowl.

I stood for a moment before my granduncle's, and wondered how he would have responded if I had told him that his distress at corruption nearly fifty years ago was merely the sense of loss of a British Raj police head-constable regretting the passing of an era.

To read the detailed version, please CLICK here!

Please send your comments to ajitb@rediffmail.com

article