| « Back to article | Print this article |

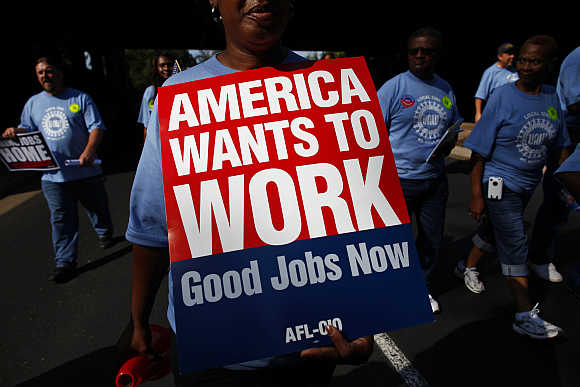

Plight of the unemployed around the world

One of the most urgent questions in economics today is the connection between inequality and growth. That is because one of the big economic facts of our time is the surge in income disparity, particularly between those at the very top and everyone else.

Click NEXT to read more...

Plight of the unemployed around the world

The other big fact is the recession set off by the financial crisis and the consequent imperative to jump-start economic growth. Figuring out the relationship between these two tent-pole issues is therefore a good way for economists to spend their time.

Click NEXT to read more...

Plight of the unemployed around the world

There are two main and contradictory ideas about how that relationship might work. One is that inequality is the price of robust economic growth. If the private sector is thriving, the most successful capitalists will be getting very rich.

Click NEXT to read more...

Plight of the unemployed around the world

Creating a system that allows - indeed, encourages - the best and the brightest to pull away from everyone else is how you shift your economy into its highest gear.

Click NEXT to read more...

Plight of the unemployed around the world

There is, however, another theory, and it has been winning adherents in the aftermath of the financial crisis. In this view, rising inequality is not a symptom of a fast-growing economy or an incentive that will help create one.

Click NEXT to read more...

Plight of the unemployed around the world

Instead, too much income inequality crushes economic growth. There are different arguments for why that might happen. One is that high income inequality creates an unstable system that is vulnerable to costly booms and busts.

Click NEXT to read more...

Plight of the unemployed around the world

Another is that when too much of the income goes to the very top and not enough goes to the middle, spending slumps - how many yachts does a plutocrat need? - putting a brake on growth.

Click NEXT to read more...

Plight of the unemployed around the world

David Howell, a professor of economics at The New School in New York, has written a draft paper for the Center for American Progress, a progressive research group, that investigates the first argument.

Howell argues that the United States and Britain have acted over the past three decades on what he calls the laissez-faire theory, that the equation of rising inequality and increasing gross domestic product is correct.

Click NEXT to read more...

Plight of the unemployed around the world

As Howell puts it, "the laissez-faire case for high inequality is grounded in the belief that growth in output and employment depends mainly on strong incentives to work and invest."

Click NEXT to read more...

Plight of the unemployed around the world

Howell tested that view by comparing the United States and Britain to their peers. He asked whether "compared to other rich countries, US income inequality has paid off in relatively high growth."

His answer: not particularly. He finds that "there is no simple correlation between our measures of growth and income inequality."

Click NEXT to read more...

Plight of the unemployed around the world

That may come as a surprise to many Americans, who are accustomed to hearing, as Howell explained, "that the US middle class is doing relatively well, at least compared to Europe, because of productivity growth and because we allow higher inequality."

Click NEXT to read more...

Plight of the unemployed around the world

But the reality is that at least some of those allegedly sclerotic European economies, dragged down by their highly redistributive welfare states, have outperformed the United States.

Click NEXT to read more...

Plight of the unemployed around the world

"What we see is Sweden having really good productivity growth by all measures, despite much more modest increases in inequality and starting at a much lower level," he said.

Click NEXT to read more...

Plight of the unemployed around the world

"The US is anywhere from an OK to middling performer in the Age of Inequality," Howell said, using his term for our era. But while his work suggests inequality is not needed to get growth, he does not show that inequality actually hurts growth either: "I don't show a strong measurable inverse effect."

Click NEXT to read more...

Plight of the unemployed around the world

Lars Osberg, an economist at Dalhousie University in Nova Scotia, takes on this second argument the case that inequality, at least beyond a certain point, can stifle growth.

Click NEXT to read more...

Plight of the unemployed around the world

He, too, adopts a comparative lens, looking at Canada, the United States and Mexico. Osberg argues that a growing chasm between those at the very top and everyone else imperils the overall economy.

Click NEXT to read more...

Plight of the unemployed around the world

His worry is financial instability. "The added savings of the increasingly affluent must be loaned to balance total current expenditure," he writes, "but increasing indebtedness implies financial fragility, periodic financial crises, greater volatility of aggregate income and, as governments respond to mass unemployment with countercyclical fiscal policies, a compounding instability of public finances."

Click NEXT to read more...

Plight of the unemployed around the world

This is a variation of an argument by Raghuram Rajan, a politically center-right professor at the University of Chicago, who has suggested that rising income inequality was one of the drivers of the financial crisis.

Click NEXT to read more...

Plight of the unemployed around the world

As income inequality increased, and the incomes of the middle class stagnated, the US government responded by increasing the consumer credit available to the middle class.

Click NEXT to read more...

Plight of the unemployed around the world

In the short term, that was a win-win solution: consumption, and therefore the economy, grew, and the middle class was quiescent because stagnating incomes were masked by increasing consumer debt.

Click NEXT to read more...

Plight of the unemployed around the world

But in the medium term that Goldilocks scenario broke down - the middle class consumption bubble, and the Wall Street bubble it helped finance, popped with devastating consequences.

Click NEXT to read more...

Plight of the unemployed around the world

Both Howell and Osberg are skeptical, at best, of the value of rising income inequality as a driver of economic growth. When you put that conclusion together with the arithmetic of democracy - rising income inequality means a majority of voters are on the losing end of the deal - a political backlash seems inevitable.

Click NEXT to read more...

Plight of the unemployed around the world

"Go back to the 1920s or the 1870s and economists were worried about the stability of the capitalist system," Osberg said.

"One of the things the 1930s experience teaches us is there are some catastrophic outcomes which can happen."

Click NEXT to read more...

Plight of the unemployed around the world

The investing class and the academic world are focused on those dangers. "Can capitalism survive?" is one of the trendiest conference topics among red-blooded capitalists and left-leaning professors alike.

Click NEXT to read more...

Plight of the unemployed around the world

So far, at the ballot box and on the street, this question has not been as salient. That does not mean it will not be in the future - and in ways we cannot predict.

© Copyright 2025 Reuters Limited. All rights reserved. Republication or redistribution of Reuters content, including by framing or similar means, is expressly prohibited without the prior written consent of Reuters. Reuters shall not be liable for any errors or delays in the content, or for any actions taken in reliance thereon.