| « Back to article | Print this article |

A $300 home for the poor? It might just be possible!

Vijay Govindarajan, one of the world's foremost management thinkers and an expert on strategy and innovation, plans to do with housing what Tata Group chairman Ratan Tata did with the automobile.

If anything, he plans to go a step further. He is confident that an affordable, environmentally friendly home can be built for just $300 (yes, $300 or about Rs 14,000!) creating a gargantuan $375-billion opportunity for corporations the world over.

Govindarajan, the Earl C Daum 1924 Professor of International Business at Dartmouth's Tuck School, has organised a global competition -- The $300 House Challenge -- calling for design ideas for such houses that would help better the quality of billions of poor people across the world, especially in developing countries.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

A $300 home for the poor? It might just be possible!

The competition that began in April will run till May end. The creators of the top three submissions will each receive $10,000, according to Govindarajan. Submissions can be sent here

Govindarajan first posed the question -- What if you could build a house for $300? -- on his blog on the Harvard Business Review web site in August 2010, along with co-author Christian Sarkar, challenging the corporate world to create a simple home that offers shelter, space, clean water, and solar power for only $300.

The $300 house, says the good professor, would be a clean, secure upgrade from the slums where a huge chunk of humanity currently resides. This will help communities and slum-dwellers lead a better, hygienic, disease-free and secure life. This 'informal settlement model' would be created by the active involvement of the dwellers themselves.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

A $300 home for the poor? It might just be possible!

The sum of $300 has been arrived at arbitrarily, but acts as a guiding light for those designing a house for that amount.

The house could be self-built as it would help lower the cost and keep the chances of 'corruption in grabbing donor aid' at bay.

These would be low-tech houses to keep the costs low, made from local -- but robust materials.

These houses would be better appointed, have sanitation and light and water and cleanliness, helping kids study and grow up in a good and healthy environment.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

A $300 home for the poor? It might just be possible!

Writing on his blog, Govindarajan and Sarkar say that they began discussing the issue 'through the lens of reverse innovation'. They soon crystallised their thoughts into the following five questions:

1. How can organic, self-built slums be turned into liveable housing?

2. What might a house-for-the-poor look like?

3. How can world-class engineering and design capabilities be utilised to solve the problem?

4. What reverse-innovation lessons might be learned by the participants in such a project?

5. How could the poor afford to buy this house?

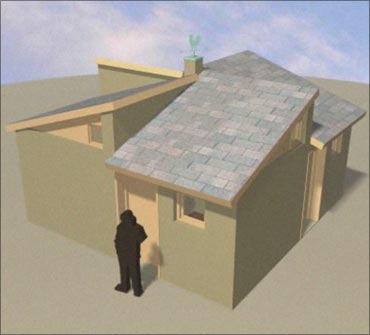

Image: Estonia, the designer, says that the material required to build this house will cost less than $300.

Photograph: Courtesy, Mashable.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

A $300 home for the poor? It might just be possible!

Govindarajan stated that their first thought was about liveable housing. They concluded that most self-built houses are normally made from easily available materials like tin sheets, cardboard, plastic, cloth, mud or clay, metal scraps, et cetera.

These homes do not have proper flooring as they are built on dirt floors. At the mercy of the elements, such huts/homes are flimsy and could collapse or catch fire.

Govindarajan and Sarkar say that the way to address this problem would be to replace these unsafe structures with a 'mass-produced, standard, affordable, and sustainable solution'.

Image: Decadomes are made from panels made of plywood, plastic, jute, rice husk, straw, and resin.

Photograph: Courtesy, Mashable.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

A $300 home for the poor? It might just be possible!

The second point was the 'look and feel' of the house. Govindarajan and Sarkar want the house to be 'an ecosystem of products and solutions designed around the real needs of the inhabitants' and made from sustainable, green materials that are robust enough to withstand heavy 'rains, earthquakes, and the stress of children playing'.

The duo said the house could be a one-room structure with 'drop-down partitions for privacy'. Minimal required furniture would be built in.

The roof of this $300 house would be an inexpensive solar panel and battery that helps provide electricity to home to light it up, charge a mobile phone, maybe power a television set.

They said that it would have a low-cost water filter, too. Govindarajan wrote that the structure is more-or-less a single-room 'shed designed around the family ecosystem, a Lego-like aggregation of useful products that bring good things to life for the poor'.

Image: Svpribyl's design uses soil and concrete.

Photograph: Courtesy, Mashable.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

A $300 home for the poor? It might just be possible!

The duo's third question focussed on world class design and, more importantly, who would do this.

They decided that this hurdle could best be crossed through a partnership between global design firms, engineering companies, and non-governmental organisations that have the requisite experience in solving problems of the poor.

Govindarajan and Sarkar also came up with names of some such organisations which could help play a major role in brining this dream to reality: The Tata Group, Siemens, Habitat-for-Humanity, Partners In Health, the Solar Electric Light Fund, the Clinton Global Initiative, the Gates Foundation, Grameen Bank, etc. They also wrote that governments 'may play an important part is setting the stage for such cross-country innovation projects'.

Image: This wigwam-like design from EarthArchitect advocates the use of bamboo sticks, and waterproof cloth.

Photograph: Courtesy, Mashable.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

A $300 home for the poor? It might just be possible!

Govindarajan and Sarkar then looked at the question of reverse innovation payoff. They concluded that corporates that involve themselves with this project would have dual benefits.

One, they would be able to reach out to a huge 2.5 billion people who make up 'the bottom of the pyramid' and serve then.

And, two, 'they create new competencies' that have the potential of transforming lives even in rich countries by applying the same yardstick and 'innovations to address issues like housing for natural calamity victims, refugees, and even the armed forces'.

Image: Pclind's idea proposes that shipping containers that are dumped could be used to provide housing to the poor.

Photograph: Courtesy, Mashable.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

A $300 home for the poor? It might just be possible!

Now came the most important question: how would the poorest of the poor be able to afford a house of their own. To become home owners and to be able to take care of these residences, Govindarajan and Sarkar drew from the social business and microfinance model pioneered by Nobel Laureate Muhammad Yunus.

They feel that 'microfinance would play a quintessential role in making the $300 house a viable and self-sustaining solution'.

Although, Govindarajan wrote, the idea of a $300 house is an 'experiment', it is an idea of major significance and something that begs to be explored.

Especially so, because, as he puts it, 'from the one-room shacks in Haiti's Central Plateau to the jhuggi clusters in and around Delhi, to the favelas in Sao Paulo, the problem of housing-for-the-poor is truly global'.

Image: This design of a shed-like home uses lightweight composite panel-building system.

Photograph: Courtesy, Mashable.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

A $300 home for the poor? It might just be possible!

A $300 house has the potential to drastically alter the lives of billions of poor people and transform slums into clean localities.

And although a $300 house might seem like a pipedream, it presents a major challenge to businesses, governments and social bodies. Not to mention an unprecedented business opportunity.

Innovations in design, mass production of materials, financing and involving the poor who are the most important stakeholders in this project could help convert this dream into reality and throw open a mega-opportunity that could spell billions of dollars in profits.

Image: This design uses adobe bricks made from dirt, water and manure and will keep the house cool in summer and warm during winter.

Photograph: Courtesy, Mashable.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

A $300 home for the poor? It might just be possible!

In an interview to Tuck Today, the official Tuck School of Business we site, Govindarajan said that the world has been divided into two by businesses. There are two billion people rich enough to buy products corporations make, and have access to education and healthcare. And then there is that world where there are 5 billion poor people who depend on charities for sustenance. And these are the people that need to be brought into the consumer base.

Doing a back-of-the-envelope calculations, Govindarajan said in the interview that for the 5 billion poor people, about 1.25 billion houses would be needed assuming that each household has a family of four. At $300 per house, that works out a massive $375 billion in potential revenue, he added.

Image: Moladi uses Lego-like plastic bricks as a foundation for affordable housing.

Photograph: Courtesy, Mashable.

Click NEXT to read on . . .

A $300 home for the poor? It might just be possible!

For the $300 house, financing too could be made easy. The total cost of the house could be paid over a period of, say, four years in equated monthly instalments. Care would be taken to see that the EMI does not exceed about 35 per cent of the household's monthly income.

Students at the Tuck School of Business are already exploring the possibility of creating a $300 home.

One group of students is looking at the feasibility of implementing this project in Haiti, while another is conducting similar research on building houses in India.

With the enormous potential that the idea has for more than half of mankind, governments, business houses and NGOs, it is only a matter of time before some breakthrough innovations do make this dream possible.

Tell us what you think of this idea and how it could change the lives of the poor.