'If you see the composition of items which are causing this spike in prices, most of them have little to do with the kharif harvest, except for pulses and vegetables to some extent.'

'I don't know on what basis the government is claiming that food prices will moderate in the weeks to come.'

Sanjeeb Mukherjee reports.

The sharp rise in food prices, seen in the last few months, may have disturbed household budgets to a large extent, but both the Centre and the Reserve Bank of India feel that things will improve as kharif harvest starts flowing in full steam.

However, experts and academicians feel otherwise as the spike in food inflation is being fueled by commodities which do not entirely rely on a good harvest.

Secondly, the harvest of several kharif crops may be more than last year.

However, unless they make their way into the market, things won't improve in a big way.

Some experts blame this on the newly passed agriculture Acts.

Their argument is that after the farm Acts, there could be a situation where large quantities of food items are being bought and sold outside the mandis of which no track is being kept, but there are several critics of this theory.

The extended monsoon has also contributed to this price spike.

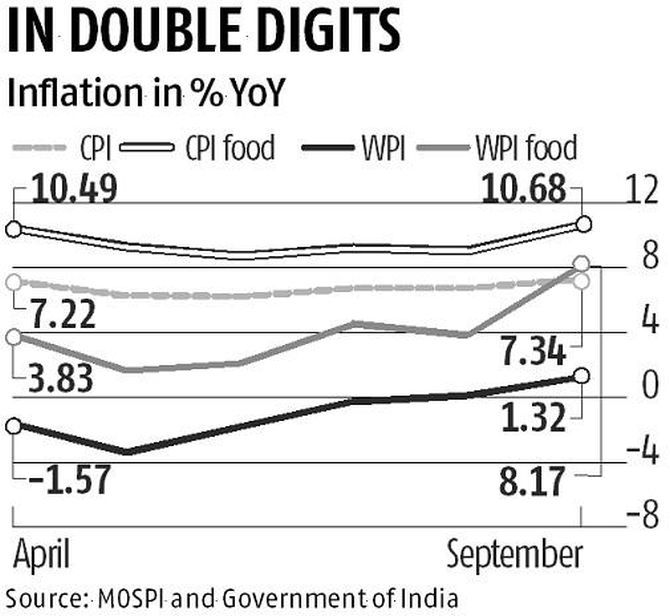

Pushed by rising prices of essential kitchen items, retail inflation rose to an eight-month high of 7.34 per cent in September 2020.

The consumer price index (CPI)-based inflation was 6.76 per cent in August and 3.99 per cent in September 2019.

Retail food inflation, in September 2020, touched a double digit of 10.68 per cent, up from 9.05 per cent in August.

The spike was largely driven by inflation in items such as meat and fish at 18 per cent, eggs at 15 per cent, oils and fats at 13 per cent, vegetables at 21 per cent and pulses at 15 per cent.

Among food items, only fruits and cereals showed less inflation at three and five per cent, respectively, in the month.

The overall retail inflation has been hovering over 4 per cent since October 2019.

The previous high in the CPI was witnessed at 7.59 per cent in January 2020.

The wholesale price index (WPI)-based inflation rose to 1.32 per cent in September 2020 from 0.16 per cent in the previous month and deflation in the previous four months, mainly on the back of costlier food articles.

"If you see the composition of items which are causing this spike in prices, most of them have little to do with the kharif harvest, except for pulses and vegetables to some extent. Hence, I don't know on what basis the government is claiming that food prices will moderate in the weeks to come," says Mahendra Dev, director of the Mumbai-based Indira Gandhi Institute of Developmental Research.

"To me, inflation will continue as it is mainly driven by eggs, meat and fish which aren't dependent on good or bad kharif harvest," Dev adds.

He expects retail food inflation to be above 8 per cent till March. This will also keep the overall inflation high.

"I think the RBI is also being slightly over-optimistic," Dev says.

Even in case of vegetables (largely onions and potatoes) and pulses, experts feel that moderation in prices will happen.

However, there may not be a big crash till the time the next big harvest comes into the market.

The Centre, meanwhile, has announced a series of steps in the last few weeks to shore up supplies of key essential commodities.

Some of these have already started showing results.

It has started the procedure to import around 25,000 tonnes of onions, 30,000 tonnes of potatoes and has relaxed norms for import of pulses to tide over the price increase.

In case of potatoes, there are plans to import nearly 1 million tonnes in the next few weeks over and above the already ordered ones at a concessional duty.

"In case of food inflation, it may remain high for a few months as the rise is more in retail markets than wholesale. This also means that traders are adding their margins which won't go away unless there is a deluge in supplies," says Madan Sabnavis, chief economist CARE Ratings.

Pronab Sen, programme director of International Growth Centre (IGC)-India, said the food inflation could be driven by demand from semi-urban and rural areas which have got some benefit from farm incomes.

"If rural demand has gone up due to good agriculture production, it could be pushing up prices, which mandis aren't capturing as much of the sales happen outside the big markets," says Sen.

"But I feel that prices will moderate once full impact of the harvest starts coming in, except in animal husbandry products."

Feature Presentation: Aslam Hunani/Rediff.com

© 2025

© 2025