| « Back to article | Print this article |

How property tax can solve India's infrastructure woes

If trained staff is employed, this revenue stream can be a big source of income for municipalities.

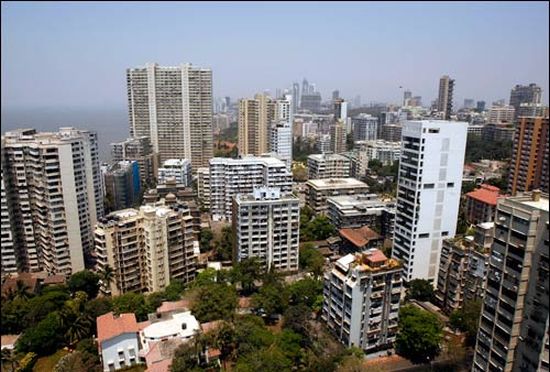

Lifting the lid on the GDP growth rate will take strenuous effort on a number of fronts, but a very key component has to be urban infrastructure.

Easier movement of people and goods within cities, functioning sanitation and sewage systems, storm water drainage - all these are essential for the economic machine to function. The problem lies with the financing of it.

Public-private partnerships are seen as the solution to the funding of urban infrastructure. It is thought that knocking the heads of municipal leaders and financial honchos together can bring about the right financial products to kick-start the process.

The problem lies much deeper, and can only be set right by getting property taxes to work. And for that, state governments have to partner the process.

Without base support from property taxes there can quite simply be no progress on urban infrastructure, except of the Mumbai sea link or Delhi metro variety catering to identifiable usage, and therefore amenable to user fees.

Click NEXT to read more…

How property tax can solve India's infrastructure woes

Private capital to fund general-purpose urban infrastructure will only be forthcoming on a time-stream of guaranteed payback unrelated to usage. Property taxes are especially suited for this because they do not carry downside risk.

The value of housing and land does not typically decline in nominal value except in extreme situations (such as the 2008 mortgage crisis in the United States), and property value is marked to market sufficiently infrequently to ride over temporary downside blips.

This makes property taxes acceptable worldwide as a reliable basis for calculating the payback time-stream for urban infrastructure funded with private participation.

Property tax revenues can only improve when the taxation structure is designed by trained professionals. Ideally, a permanent core of personnel in a state-level property tax board could provide expertise to all municipalities in the state, big and small.

The 13th Finance Commission made a first and much-needed step in this direction by requiring the setting up of state-level property tax boards as a conditionality for a performance grant to urban local bodies, over and above an unconditional basic grant.

Click NEXT to read more…

How property tax can solve India's infrastructure woes

Progress on this and other conditionalities is not yet displayed on any public website. Information accessed from the National Institute of Urban Affairs shows that as of March 31, 2012, the latest available, 18 states had set up state-level property tax boards.

But in many of these, the board is a mere shell, not functional in any sense because there is no budgetary provision for technical personnel.

The 13th Finance Commission performance grant flowed directly to urban local bodies, with no part going to state governments to fund the property tax board.

The intent (not explicitly stated in the report) was to have these bodies function on a commission basis, getting a small part of the increment in property taxes as a result of their services, but clearly an initial budget line is needed for hiring qualified technical personnel in the first place, with a training provision if necessary.

The incentive to states, of having additional grants flow to municipalities from the Centre, should have sufficed just by itself.

Click NEXT to read more…

How property tax can solve India's infrastructure woes

But apparently, states see the property tax board as an unfunded mandate, instead of as an opportunity to free municipal governments from continued financial dependence on state governments.

Property taxes are not popular. There have been state elections in which parties rode to power on a manifesto that included the promise to repeal property taxes.

People see the income tax or sales tax as justifiable, but to be taxed for just living in a house strikes them as monstrous.

For this reason, it is especially important that property taxation should be fair, and seen to be fair.

Over time worldwide, property taxation practice has moved away from intrusive checking for internal opulence (marble floors, gold faucets), to more macro assessments of the taxable base, by differentiating between cities, and between zones within cities, by market value.

Click NEXT to read more…

How property tax can solve India's infrastructure woes

But even such a seemingly simple exercise calls for assigning a rateable value per unit floor area based on location. Smaller municipalities have no way of getting such technical expertise by themselves.

The year 2010-11 was a gap year given to states to get their act together on the qualifying conditionalities for the urban performance grant.

If they came up against a budget constraint for a new line-item for the property tax board, this was an issue they could have brought to the nodal ministry. The amounts are so small that a solution could easily have been worked out.

Revenues currently collected through property taxation in the country are not known with any certainty. There is no annual issue of audited finance accounts for local bodies in aggregate, of the kind available for state governments.

Data supplied by states to Finance Commissions are the only source of information on own revenue collected by municipalities, but these display such inconsistencies across Commissions as to be not plausible.

The 11th and 12th Finance Commissions incentivised own-revenue collection by local government, but those very incentives introduced an upward reporting bias in later years.

Click NEXT to read more…

How property tax can solve India's infrastructure woes

If the figures are taken just as they stand, own revenue of municipalities stood at at 0.47 per cent of GDP in 1990-91 (the first year of the series collected by the 11th Commission), and remained at 0.47 per cent in 2007-08 (the last year of the series collected by the 13th Commission).

The true figure for 2007-08 is likely to have been much lower.

These are for total own revenue, and cover cities located in states like Mumbai, but exclude Delhi and other Union Territory cities (for which audited figures are indeed separately available).

They include revenue in earlier years from octroi, a levy on goods at the urban entry point. Octroi has since been dropped, so property tax collections do seem to have risen to some degree to cover the revenue loss from octroi.

There is room for a further huge leap in property tax collections with better coverage of the taxable base, given the increase in the housing stock over the last two decades.

Once the funding for staffing and training of property tax boards is addressed, that potential can be realised, and provide the revenue base for private funding of general-purpose infrastructure across urban India.

The writer is a retired professor of economics