As a government-owned behemoth, Life Insurance Corporation managed to stay ahead of the competition when the sector was thrown open - but only with some painful changes.

Recently, S K Roy, chairman and managing director (CMD) of Life Insurance Corporation (LIC), said the public sector insurance company would launch a new unit-linked insurance plan (Ulip) by March 2015.

According to experts, the lack of Ulips in its portfolio was one reason for the fall in LIC's new business premium collection in the first half of 2014-15.

LIC's market share in first-year premiums fell from 75.3 per cent in 2013-14 to 72.8 per cent in the first half of 2014-15.

There's a certain irony in this, as LIC was the first insurance company to launch a Ulip, way back in the early 2000s.

"LIC brought out the first Ulip, Bima Plus, in the newly opened insurance market in 2000-01," said Thomas Mathew T, former CMD of LIC.

This launch was not without its internal issues for a conservative organisation. As another former chairman, S B Mathur, recalls, when the insurance sector was opened, LIC was criticised for not offering Ulips with their potential for offering higher returns.

"Our agents did not want to sell Ulips as these were risky products. Then, I suggested agents sell Ulips to those who could understand it. And, made it mandatory for agents to sell at least two Ulips," Mathur said.

In 2002-03, LIC sold 300-400 million Ulips, against three-four billion sold by the private sector. By 2004-05 (when Mathur retired), LIC sold the highest number of Ulips in the industry.

LIC continues to be a conservative organisation. Apart from staying away from Ulips in the current market, it stayed away from joining the bandwagon of online term plans for a very long time.

It launched its first online term product earlier this year.

Much of this tardy reaction to competition is the result of LIC's legacy.

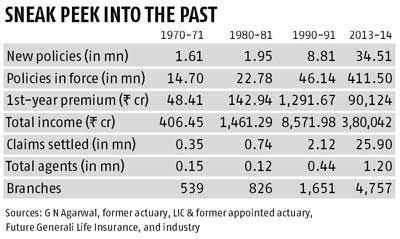

The 1970s, recalls former actuary G N Agarwal, was a difficult period for LIC due to slow business growth, high expenses, centralised services and absence of technology. Several efforts to change were made.

"T A Pai, then chairman, made a lot of changes. The government appointed many committees - the Morarka Committee in 1972; Era Sezhiyan Committee and Jagannathan Committee in 1978-80 - to look into LIC's working and suggest changes," Agarwal recalls.

Computerisation, too, progressed at snail's pace. Mathur recalls LIC took its first step in the 1960s.

"There was just one computer in the Mumbai office, a Classic IBM 1040. Another computer was sent to our second biggest office in Calcutta. However, the CPM government did not let us use it," he says.

It was only in the 1980s that computerisation gathered momentum (today, LIC functions with 2,048 fully computerised branch offices).

Mathew says this was the biggest cultural change LIC saw before the sector opened up. LIC and the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) were the first two public sector institutions to adopt computers.

The process took a long time to complete as it involved the back-end, front-end, local area network, wide area network, software network and so on.

This was long before the internet. Then, there was computer and software evolution to deal with. Mathew recalls when one of LIC's rural branches was getting computerised, nearby villagers had come to see what a computer looked like.

"At that time, I was heading the Gwalior branch," recalls Mathur.

"If a computer developed some problem, we had to call engineers from Delhi."

They would take the Shatabdi Express the next morning and were most likely to dismiss the glitch as a software problem.

Then we had to call for a software engineer, who was equally less likely to accept it as a software issue.

Then we would request both engineers to work together and solve the problem. Thus, it would take three to four days to solve one computer problem, he said.

Decentralising all its functions was another big change for LIC. Services like policy processing, change of address, nomination, loan settlement, underwriting and especially claim settlement had to be taken to zonal and branch offices, against only the divisional offices.

Claim settlement and paper processing could take as long as 60-90 days.

Mathur recalls how it took one year for his family to get the claim money after his father's death, due to some issue with nomination.

Today, the regulator gives insurers only 30 days to settle claims.

The employees' union had also opposed computerisation, says. Roy. "They thought computerisation would mean job loss. But, given we were decentralising our functions, we needed to add employees."

Claim settlement was made the focus in the 1980s and it helped improved LIC's image widely, said Agarwal.

LIC also launched many new products in this period and increased the bonus for with-profit policyholders (those who owned participating policies would get a share of profit as bonus).

Despite its conservative nature, LIC always charged a higher premium for its policies.

Most private players' term plans of Rs 50,00,000 for 20 years cost Rs 3,500 to Rs 5,500 annually. LIC's Amulya Jeevan II costs Rs 9,200.

The time the sector opened was also when the Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority (Irda) was set up.

The change in the sector did not have a huge impact on LIC, say its former executives.

That was because LIC had to play big brother to both the competition and Irda, mainly because it had all the data (especially mortality data) required to set industry standard.

This apart, LIC provided staff support to Irda and also helped it with a place to set up its office.

At that time, Mathur was at the helm. He recalls taking some tough decisions.

He discontinued policies like Jeevan Akshay and Jeevan Dhara, which paid almost one per cent a month.

Comparatively, the yield on a 10-year government security stood at 5-5.5 per cent. There were questions raised about this in Parliament and it was said LIC was ceding market share to private players.

As a result, first- and second-year new business premium collection declined. But the renewal premium growth was healthy, recalls Mathur.

Second, LIC had capital of only Rs 5 crore or Rs 50 million when the minimum capital requirement for life insurance companies was Rs 100 crore or Rs 1 billion.

Mathur said the government required to pump in capital. Instead, the regulator questioned LIC's solvency and asked it to raise its solvency margin to one per cent.

Today, insurers are supposed to maintain a solvency margin of 1.50 per cent.

When competition increased, Agarwal adds, one more big change that LIC adopted was to increase its distribution channel from only agents to bancassurance, corporate agency, micro insurance and so on.

This also helped the firm maintain its market share.

But one thing that did not change at LIC in so many years was the mandate given to the agents - suggesting investment plans for every possible lifecycle need, under the guise of advice. Agents' motivation: Huge commissions.

In its early days, LIC enjoyed the best of talent available in the market as there weren't many job options. Mathew fondly says he started his career at LIC and went on till retirement.

The sentiments are echoed by Roy. However, he says LIC should increase its pace of change as regulations are changing fast.

And, large organisations have to adjust more. "Also, resources and technology should be used efficiently to increase productivity," he adds. He says LIC's biggest strengths are its strong brand and after-sale service.

Mathew says the image of LIC agents in society also needs a makeover. While LIC still depends heavily on its agents, socially earning from an agency is still not looked at as a sophisticated career option.

© 2025

© 2025