The Modi government will have to move fast, and carry the state governments along, before the window for radical reform closes, says Vijay Joshi.

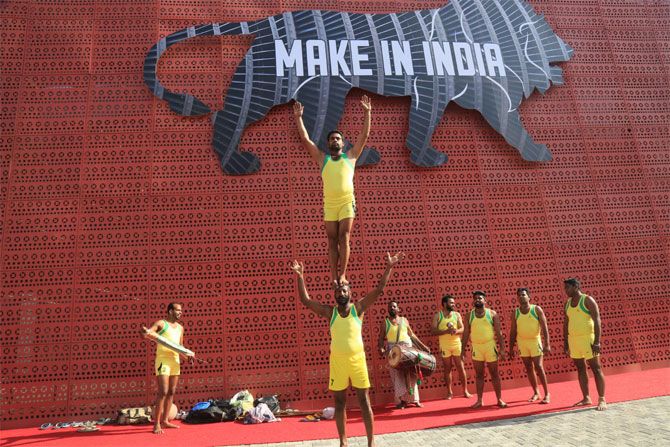

Photograph: Reuters

The Narendra Modi government has been in office for more than two years, and the monsoon session of Parliament is about to begin.

I assess the government’s economic performance thus far in seven critical areas.

In the last three of these, my discussion is very brief because there has not been much policy movement to assess.

The relevant arguments are fully spelled out in my new book (see below).

Macroeconomic stability: On this count, the government’s performance has been creditable though a lot of credit also goes to good luck: the crash in oil prices in 2014 had a large direct and favourable impact on inflation, the current account deficit and the fiscal deficit.

That said, many of the technocratic decisions were also sound. On monetary policy, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) held its nerve despite loud calls for lowering interest rates prematurely.

Inflation is now less than six per cent a year despite two indifferent harvests. The government has adopted “inflation targeting”, a sensible decision for the long term.

On micro-fiscal policy, it wisely used the oil-price fall to reduce fuel subsidies.

On macro-fiscal policy, it made a small and justified one-year deviation from the roadmap for fiscal consolidation (in order to boost public investment) but prudently chose not to deviate for a second year.

The fly in the ointment is exchange rate policy. Exports have collapsed. The world economic slowdown has not helped but neither has the RBI’s exchange rate management.

The real exchange rate was allowed to appreciate by around 10 per cent over two years, a questionable policy choice.

A competitive exchange rate is necessary (though not sufficient) for vigorous export growth.

Investment climate: How much has changed on the ground as regards “ease of doing business” is not clear but movement is certainly pointed in the right direction.

The immediate problem is that the combination of a debt overhang in the corporate sector and impaired balance sheets in the banking sector is holding up a revival of private investment.

The RBI has quite rightly been pushing to make public sector banks (PSBs) “recognise” bad assets. But bolder policies may be needed for cleaning up the balance sheets of PSBs, accompanied by recapitalisation.

If the government is lucky, a strong upswing will come spontaneously and the situation will ease.

If it is unlucky, the problems will continue to fester. Right now, the recovery looks weak (except in the national accounts statistics!) Moreover, any recovery so far has been consumption-based, not investment-based.

Pattern of taxation and government expenditure: The GST is still bogged down in Parliament.

The enormous burden of explicit and hidden subsidies (for food, fertilisers, various fuel products, electricity, water, rail services etc.) continues unabated, despite full recognition of the problem in the government’s Economic Surveys.

These subsidies are inefficient, regressive and wasteful.

By retaining them, the country is foregoing a huge potential fiscal gain that could be used to increase public investment in physical and social infrastructure, and to eliminate poverty by making cash transfers.

The government has put energy into extending the coverage of bank accounts and Aadhaar. But it has not taken the major steps needed to use these platforms for overhauling the subsidy regime.

Markets, ownership and regulation: There are a few pieces of good news.

A bankruptcy law has been passed though the accompanying institutional infrastructure will take time to develop.

The RBI has allowed and encouraged the entry of new banks designed to widen financial access.

The government has decided to introduce a crop insurance scheme and has strongly encouraged the development of solar energy.

On the negative side of the ledger, reform of land and labour markets has gone approximately nowhere.

On privatisation, the government (unlike the BJP government of 1999-2004) appears to be stuck with the fetish of 51 per cent ownership. The moves to improve governance in public sector banks have been extraordinarily timid.

There has been a strong push on some aspects of infrastructure investment but the modalities of managing public-private partnerships remain unsatisfactory and unreformed.

There has been another bail-out of state electricity boards but no comprehensive programme for sectoral reforms in pricing, ownership, competition and regulation.

Without these, the bail-out amounts to kicking the can down the road. In agriculture, there has been no meaningful policy change to improve the supply chain from farm to consumer or to overturn the perverse mix of high subsidies and low public investment. There is near-stasis on environmental policy.

External economic engagement: A major plus point is that direct foreign investment has been substantially liberalised and is being courted energetically.

But trade liberalisation is at a standstill. The tendency to want something for nothing in trade talks is still in evidence.

There is no coherent policy towards mega-regional agreements, which are increasingly a force to be reckoned with in world trade.

The welcome recent changes in textile policy, especially the duty drawbacks and the wage subsidy for additional employment, could assist an export drive.

However, Indian exports, including textile exports, will continue to face higher tariffs (relative to those faced by competitors), in the absence of progress on trade agreements.

Social protection and enablement: The government has wisely decided to continue the rural employment guarantee scheme for the time being.

But price subsidies remain the main (and broken) model for redistributive income transfers.

In education and healthcare, there is no indication that the government is facing up to the profound incentive and accountability problems involved in service delivery by the state, and the challenge of harnessing and regulating private-sector supply.

Reform of the state: Nothing has been done to repair the large deficits in administrative, police, and judicial capacity, or to attack the mainsprings of corruption and crony capitalism by cleaning up election funding and the finances of political parties.

On balance, the economic record of the government has been decent but underwhelming.

Democratic governments usually have a short electoral window for decisive action.

The Modi government will have to move fast, and carry the state governments along, before the window for radical reform closes.

Success will require political skill, not just economic expertise.

The writer is an emeritus fellow of Merton College, Oxford. His new book, India’s Long Road: The Search for Prosperity has just been published by Penguin.

© 2025

© 2025