Close to a million small shareholders have stake in nine NCLT-bound companies

Illustration: Uttam Ghosh/Rediff.com

The Securities and Exchange Board of India (Sebi) has extended a helping hand to the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) in the war on stressed assets by relaxing a couple of regulations to enable a turnaround of distressed companies.

After representations that the pricing and open offer obligations might put off potential investors in these companies, Sebi in its board meet recently decided to provide these exemptions.

Official statements said the exemption from open offer under the takeover regulations would be applicable for resolution plans approved by the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT) under the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016.

In addition, investors buying shares in these companies from banks that had converted their debt as part of strategic restructuring would be exempt from open offer obligations.

The pricing regulations under the Issue of Capital and Disclosure Requirements (ICDRs), which would be applicable in case the new investor opts to infuse capital directly into the distressed company, have been done away with.

While the move has been hailed as a much-needed relief by the banking community and analysts, minority shareholders stuck in such companies might not see this as a pure blessing.

A glimpse of the minority shareholder population and profile in the first set of 12 companies that are bound to the NCLT underlines the extent of the impact of the rule.

Close to a million small shareholders hold shares in nine of these, which are listed.

Top institutional investors such as Life Insurance Corporation of India, Blackstone, Religare, HDFC Mutual Fund, and UTI Mutual fund have a significant exposure to these companies.

While not much noise has been made by these shareholders yet, minority shareholders have become more assertive even in private companies.

By waiving the open offer requirement, the banks effectively get an opportunity to offload their shares at higher prices, which are not available to other shareholders.

Is the minority getting a raw deal?

Shriram Subramanian, managing director, Ingovern Research Services, says these relaxations might not help the troubled companies or the investors in a big way.

“It is like saying: You want to go to moon, let me open this gate for you,” he says, suggesting the resolution of the problems in these companies would take substantially more pain and effort.

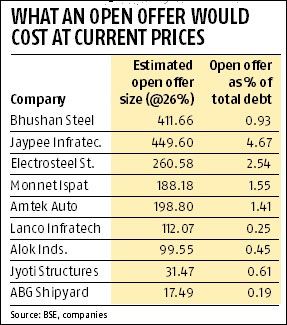

While the debt of the big 12 companies earmarked by the RBI for insolvency is more than Rs 2.5 lakh crore, the cumulative cost for 26 per cent open offers for all the nine actively traded listed companies among these would have been less than Rs 1,800 crore, despite the recent run-up in prices in some companies.

While the debt of the big 12 companies earmarked by the RBI for insolvency is more than Rs 2.5 lakh crore, the cumulative cost for 26 per cent open offers for all the nine actively traded listed companies among these would have been less than Rs 1,800 crore, despite the recent run-up in prices in some companies.

In five of these companies, the open offer would be less than 1 per cent of debt outstanding (see table).

Analysts who have welcomed the move say that if minority shareholders don’t sacrifice, they would be worse off because these companies will run aground, whereas if a new investor comes in, there is a chance of a turnaround.

Harish HV, partner, India leadership team, Grant Thornton India, says an open offer is not the only form of exit for a minority shareholder in a listed company and the relaxations could benefit the investors.

“It gives them an opportunity to participate at the price which an acquirer is paying but only for a portion of the shares. Given that stressed companies are in trouble and headed for liquidation, the shareholders will end up getting nothing.”

But, this has been heard before. For many of these investors, this is the second time they are being denied an exit.

In 2015, when strategic debt restructuring (SDR) came into effect, Sebi had exempted banks from making an open offer.

At that time, there was a lock-in of one year for banks on condition that if banks transferred shares, the lock-in would also move to the transferee.

However, despite the relaxation, not much happened in these two years, making the government and RBI come up with a fresh plan.

When asked after the board meet whether there were enough safeguards for the minority shareholders, Sebi Chairman Ajay Tyagi said the new investors, who have a three-year lock-in, would have to be approved by the shareholders by way of a special resolution.

The notice to shareholders will have to include details like identity of buyers, their business model, and credentials.

“This will hopefully take care of the minority shareholders' interest in these companies,” he added.

While the longer lock-in period comes as an additional cushion, there are voices that these could be a hindrance to resolution. Further, these cushions would not be available when the company goes to the NCLT under Insolvency law.

The insolvency law does not provide for any representation by the equity shareholders as lenders would call the shots here.

On the special resolution, which might come into play when banks transfer their shares, it is not yet clear if they would be able to vote. According to related party rules of Sebi, a person interested in a particular resolution is supposed to abstain.

“If the banks are allowed to vote, there is no meaning in saying that the special resolution is a safeguard. Then, every resolution will pass,” says JN Gupta, founder, Stakeholders Empowerment Services.

The jury is still out on the fate of minority shareholders in the stressed asset resolution process.