Choice of jurisdiction is important as that decides which country's law would apply in settlement of the dispute, says Sudipto Dey.

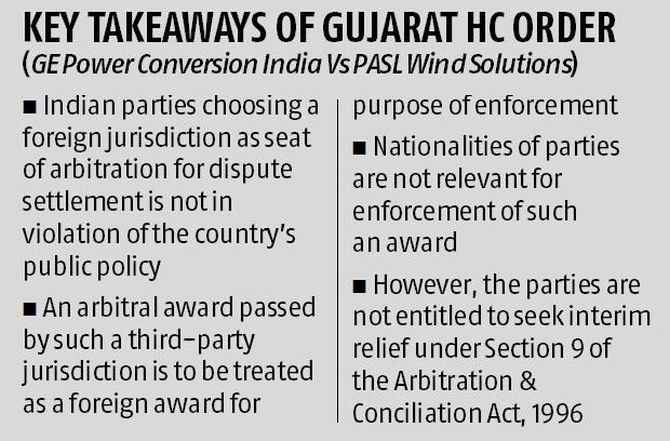

The Gujarat high court order that allows Indian companies to choose foreign jurisdiction for settlement of domestic dispute through arbitration proceedings has been hailed in legal circles as a landmark ruling.

Experts explain how it will influence India's alternative dispute landscape.

Why is the Gujarat high court order being considered a landmark ruling?

This opens the door for Indian companies to seat their arbitration outside India.

Legal experts point out that there have been several conflicting judgments of various courts on the issue of whether two Indian parties can choose a foreign seat for dispute settlement.

The Gujarat high court ruling says that there is no embargo on Indian parties choosing a foreign seat.

Choice of jurisdiction is important as that decides which country's law would apply in settlement of the dispute.

However, the Gujarat HC rules that any arbitral award emanating from such a proceeding would be treated as foreign award.

But this also comes with a caveat. Interim relief would not be available in India to such an award.

“This is in line with previous decisions of other high courts and the Supreme Court, but is a landmark as it give clarity on this issue,” says Tejas Karia, partner & head, arbitration, Shardul Amarchand Mangaldas & Co.

Experts say this ruling could influence Indian-owned companies and Indian subsidiaries of MNCs to choose third-party jurisdictions for dispute settlement.

According to Vyapak Desai, partner at law firm Nishith Desai Associates, this ruling may take certain kind of disputes outside India, and would further make foreign seats more attractive.

Most experts feel that the case is likely to go up to the Supreme Court for a final view on the matter.

How will this order play out if one of the parties is non-Indian, or if both the parties are Indian?

Experts point out that if one of the parties to the dispute is non-Indian, they are permitted to choose a foreign seat for arbitration, and treated according to the regulations for international commercial arbitration.

“Insofar as two Indian parties to what would otherwise be a purely domestic arbitration is concerned, the ruling recognises that even in such cases parties are entitled to choose a foreign seat, thus respecting and upholding party autonomy,” says Shaneen Parikh, partner at Cyril Amarchand Mangaldas.

To what extent would absence of interim relief to parties influence their decision to choose a third-party jurisdiction?

Legal experts see this caveat as a dampener in an otherwise progressive ruling.

The court rules that to be treated as an “international commercial arbitration”, at least one of the parties involved has to be foreign.

Two Indian parties choosing a foreign jurisdiction for arbitration does not fulfil that criteria.

“Because of this aspect of the decision, parties may be hesitant to choose a foreign seat. However, the case has at least clarified that in principle there is nothing wrong with a foreign seat,” says Parikh.

Karia points out that the parties' choice of a foreign seat will now be based on an analysis of whether they prefer a foreign court's supervisory jurisdiction over the arbitration, combined with a lack of interim measures from Indian courts, or whether it is more beneficial for them to have Indian courts' supervisory jurisdiction, as also the ability to seek interim measures before Indian courts.

Does the ruling have an adverse impact on India's aspiration to an international arbitration centre?

Most experts feel that this ruling, and the recent Ordinance to amend the arbitration Act, would strengthen India's image of having a pro-enforcement approach to arbitration.

Desai, however, is not in favour of enacting laws through Ordinance, and without any public debates. “The need of the hour is to take stakeholders' comments before passing of laws,” he adds.

© 2025

© 2025