Darjeeling is on the boil over the demand for a separate Gorkhaland state.

June and July are bad months to have a strike.

Tea picking during its most valuable season has been affected.

Those consequences will be felt all over the world and ultimately damage Darjeeling tea.

'If your girlfriend is away, you will still love her. But if you do not see her for long, your love may fade away over time. And you have to look elsewhere.'

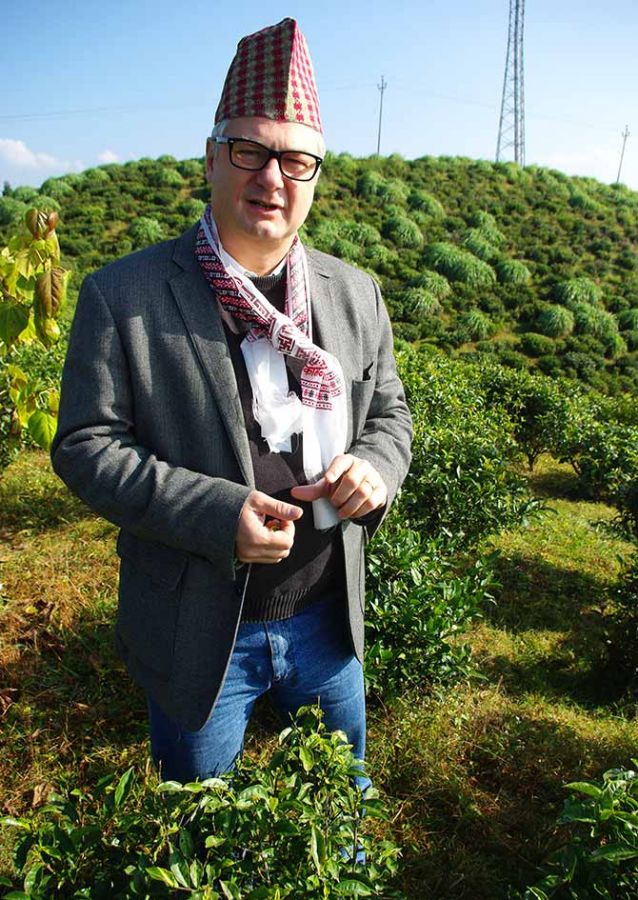

Marcus Wulf, a German tea importer and managing director of Hamburg Tea, recently made news, and received a flurry of interview requests, when he offered this succinct girlfriend statement to The Telegraph newspaper, on the potential outcome for Darjeeling tea if it absents itself from world markets for too long, because of the troubles its growing areas are facing.

This well-wisher of Darjeeling tea describes himself as a sort of tea scout.

Being both a tea broker and trader, he says he has to be the link between the green leaf of the tea industry and the final consumer's cup of tea.

Love of Darjeeling chai runs in Wulf's veins. His father was a successful post-World War II tea trader and an avid fan of Darjeeling tea. He had a key role in transforming first flush Darjeeling black teas, along with tea dealer Ranabir Sen, so that they had the 'more complex aromas and oolong-like subtleties' now associated with this classy tea.

Hence, Wulf's concern for the fate of Darjeeling tea is akin to anxiety for a family member and needs careful hearing.

The present unending strike in Darjeeling is happening smack in the middle of its tea's peak season and could be quite damaging for the income of the region, even if normalcy returns because this crucial season would have been missed out.

Wulf told The Telegraph: 'If the gardens do not survive, it would not help them in the long run even if they get their own state. Where will people go to work in the future? They must ask themselves if this is the right time to strike?'

Hamburg Tea is a major importer and broker of Darjeeling tea into Germany.

Darjeeling's exotic and highly-priced second flush tea (which is the result of picking between May and July) is popular in Germany.

Rediff.com's Vaihayasi Pande Daniel spoke to Marcus Wulf to understand his concerns for Darjeeling tea.

The strike has prevented the picking of second flush tea leaves.

Photograph: Ashok Bhaumik/PTI Photo

What are your main anxieties about the present unrest in Darjeeling?

That the people in Darjeeling and the tea producers might suffer (indirectly) because of the political turbulence in the long run.

With or without Gorkhaland, some revenue has to be achieved in the future. The situation looks anything but pretty for some years.

The question is: Can Darjeeling survive just on the booming tourism etc alone?

Also, what will happen to tourism if the tea industry is not flourishing?

I believe that many international tourists also come because Darjeeling is well-recognised as a high quality tea producing area.

Not only for the mountain views and trekking.

There are fears of an already declining supply because of issues relating to replantation. What is your take on that problem?

If there is limited second flush tea available, the final customer has to live with that.

There might be some stock position from the previous years with the traders/packers, but also last year was bad, quality wise.

I doubt that the consumers will stop drinking tea. But they will have to look left and right in the basket of great teas being produced worldwide.

Once they get acquainted with teas they have not tried before, they might stay with these.

When in fall 2018, the new second flush will be available, the risk could be that some consumers have shifted to other teas.

In addition, with the financial situation the Darjeeling producers are in now -- and have been already before the strike -- it will be truly challenging to make fabulous teas.

I am not talking about the weather patterns, which have been everything but favourable.

But the industry is not, year on year, investing enough in these leaves to maintain or improve quality.

The industry is not putting enough money down on its workers either.

Tea workers are seen here plucking tea leaves after offering prayers to the season's first crop in the Sukana tea garden estate on the outskirts of Siliguri a few years ago.

Photograph: Rupak De Chowdhuri/Reuters

In your experience, what is it about these issues that the tea workers do not understand?

I am pretty sure that the tea workers understand clearly what is happening.

Aggression may be caused by few on both sides.

Generally people in the hills have good common sense.

They have clear intentions of what they wish to achieve. Those are certainly -- which is what all of us wish for -- long-term stability, fair working conditions, treatment and income so that their living standards will gradually improve.

A system, of course, where their cultural background is appreciated and accepted.

In your view, what are the most important things the Government of India and the leaders of the tea industry must do to protect its famous brand?

I am in the tea trade, not a politician.

You get fame for something really great. You get good money for something outstanding, because the demand is there.

If the circumstances are not allowing the tea producers to make a fabulous product, because they are not able to invest more into the workers, gardens, factories and roads etc, as in the past, the fame will vanish day by day.

Along with this, there will be a decline of achievable prices and vice versa.

It is difficult to return now. But the answer cannot be a mass product, sold in large blends, at a mediocre price, for teas produced in the peak seasons (like) first or second flush, whose qualities neither represent nor are according to the quality a final consumer should expect and wants.

If the blend business is more important than the 'true' quality business, which in general should achieve higher prices then blends, it can be done.

But if too much prime quality leaf is wasted in middle-class blends, it will not help the purpose, which is to achieve the best possible revenue for Darjeeling teas.

If you look at other quality producers -- for example, China -- they make quality teas which partly reach 10 times the price of a good Darjeeling.

They only produce tea for a limited period (reduced supply), all is handmade and they have a clear perspective on the costs, as they only need to employ workers/pluckers for a certain period -- who are, in fact, paid much higher than in India.

If tea is not profitable, (China) could grow another commodity in their fields.

This, of course, is a system that has a much less of a social net, but it is highly profitable. I am not saying it is better.

If you look into Darjeeling (tea gardens) the producer can only produce tea -- with few exceptions like tourism -- and has to carry the burden for all costs 365 days in a year independent of the revenue, weather, quality and market price etc.

The worker needs to get paid better year by year which is necessary too (inflation, improvement of living standard etc).

Sometimes I think the situation is a tight corset and I can see what it does to the industry.

'It tends to exaggerate and likes to compare apples and pears -- a basic worker in India versus a basic worker in England or Germany.'

Photograph: Rupak De Chowdhuri/Reuters

From the business point of view, what is your interest in Darjeeling's tea industry?

My core interest lies in the tea industry being a profitable industry, with fair prices for the producers, fair treatment and payment of the workers engaged so that it becomes more sustainable.

The international press likes to focus on tea and how bad everything is. I don't know why.

It tends to exaggerate and likes to compare apples and pears -- a basic worker in India versus a basic worker in England or Germany.

One thing is clear: We all like to be in this good business.

The tea industry, and the tea workers should enjoy a comparatively good living and working conditions. We need to improve on this.

We should focus on getting more money for the product.

International and Indian national tea buyers must pay higher prices for tea in general (not only for Darjeeling), to make the whole industry sustainable again.

(I am involved with) quality assurance, tasting, advising, blending, seeing production, learning and helping how to improve -- all in the interest of making good tea, at fair prices, for all, and selling good teas on the shelves for the final consumer.

(I am interested in) fighting against mass products and comparatively cheap blends and the downtrend in quality.

Having said all that, I need to point out that naturally my companies are focussing on making money every year.

There is no doubt about it. We are not a social institution. Nor should a producer should be happy to produce losses etc -- to a big degree, having enough profit at the end of the year in your individual enterprise is a part of true sustainability.

How did you get into this profession? And why did it interest you?

My father was a tea trader already, who started his career in 1952 as an apprentice in a large tea company in Hamburg. He worked in the trade till 1996.

After school and two years of service in the German army, I did a two-year bank apprenticeship, followed by two years as a junior account manager in Hamburg, at a Dutch merchant bank.

In 1991 I started working in tea in full time.

In your words, what is unique about a cup of Darjeeling tea?

Tea-tasting is a wide field.

My father taught me to only buy teas that make you smile.

This refers to first flush, second flush, autumnal and to the rain teas.

Of course, they are all different in seasonal character, estate, every section, every day, leaf grade and every single leaf itself.

I like this huge variety.

How can the quality of Darjeeling tea actually improve?

Invest in the fields, the workers, finer hand-plucking, better field control, the know-how and skills.

A lot of manual work is needed and a lot of knowledge.

Will it be paid by the market nowadays is the question.

Doing all this brings up the costs enormously.

Not doing anything will further push the downtrend of quality and price and ultimately more and more blend business will be the result.

The teas from the rain period, the brokens, fannings and dusts are the most crucial problems which cannot be avoided.

Making teas in the rains is a financial challenge for many Darjeeling estates, as mostly not profitable.

How popular is Darjeeling tea in the places you bring it to Germany, Japan and which teas are overtaking its popularity?

Darjeeling is still very popular in Germany.

Plus, many trading companies here purchase for the worldwide trade too, for smaller units, just in time blends, quality control, seasonal buying etc, which is not possible for everybody in the worldwide industry.

Workers at the Dhagapur tea garden estate, on the outskirts of Siliguri.

Photograph: Rupak De Chowdhuri/Reuters

You mentioned that the international press likes to focus on how bad everything is for Darjeeling tea producers and their world?

In your estimation, why do you think that exaggeration happens and how much worse, would you know, are their conditions from say the tea worker in China or Kenya?

From my point of view, the working conditions in the Darjeeling tea industry are not great, but truly not disastrous.

They should be gradually improved.

But if you look at India I do not think that they are worse than many other industries. Rather better.

There is certainly a problem in remote areas. They need to live with sometimes poor infrastructure – the workers and their families.

I strongly believe that the tea industry doesn't (do badly) if you do a direct comparison to (workers of) certain other industries/farming area etc.

As we all know, besides the wages, there are all kind of incentives on top, which many other industries do not provide.

Also, here one has to look at it economically, I think.

If our industry does not provide proper jobs, with fair pay, to make the life of the worker families worthwhile, we will lose them and they will escape looking for other, better jobs.

If there are no workers, there is no question of hand-plucking.

Machine plucking will bring down the quality exorbitantly (and the prices for sure).

It should be the job of the tea industry to get good prices for their product, so they are then able to provide well-paid jobs to the tea worker.

If the industry can not afford it, they will lose their workers anyhow.

Good revenue and interesting, fairly-paid jobs and working conditions are completely connected.

To make it all sustainable, we need higher tea prices in India (being the highest consumer of Indian tea) and, for sure. worldwide.

I understand your family has an old connection with Darjeeling and your dad's ashes came to be scattered in Mirik (about 60 km from Darjeeling). How did this relationship come about?

My father, Bernd Wulf, born 1930, was a true tea aficionado.

He loved Darjeeling very much and, in fact, changed part of the production style together with Ranabir Sen (J Thomas) in the 1960s and 1970s, I believe.

When my mother passed away in 1998 he told me that he wanted his ashes to be scattered over Dareeling.

He passed away 10 weeks after my mother in 1998.

I then selected the Darjeeling estate Okayti, run by the family Kumbhat, who are our friends for two generations now.

Workers are seen here returning to their homes after the day's work at the Gulma tea garden estate, near Siliguri.

Photograph: Rupak De Chowdhuri/Reuters

What is special about Darjeeling for you?

In 1982 I stayed for three months in India with the Kumar family, some other close friends of ours for even longer, in Kolkata.

My first trip to a tea estate ever was to the Namring tea estate of the Poddar family (an hour from Darjeeling at an altitude of 1,700 m).

I stayed there for a week or so. It changed my life and I fell in love with tea right away and still I am.

Waking up with the siren of the factory, (the fragrance of) freshly withered leaf, having a cup of tea and looking at the Kanchenjunga... Can there be anything better?

© 2025

© 2025