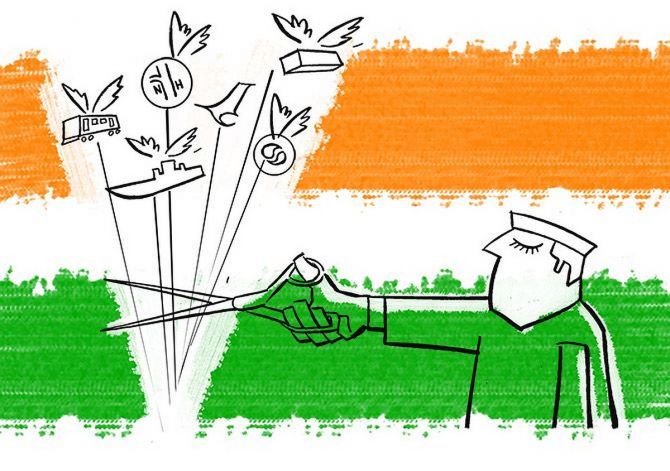

State-owned companies have been set stiff targets to increase accountability as they get ready for divestment.

Nikunj Ohri explains why meeting them will be challenging.

In trying to meet its ambitious divestment target of Rs 2.1 trillion for the current financial year, the government plans to push ahead with stake sales of public sector units in the market.

Raising income from divestment has become even more critical this year as the government seeks to finance infrastructure and other spending to revive the pandemic-hit economy.

But in doing so, it is facing a troubling issue.

Public sector enterprises have seen their market capitalisation drop 16.6 per cent since the beginning of calendar 2020, against an 18 per cent rise in m-cap of all listed companies during the same period and this is true for peer-to-peer comparisons as well.

For example, State Bank of India, the country largest bank, has a market cap that is a third of its private sector peer HDFC Bank.

This is the case with many public sector companies, where valuations is a concern and the government faces difficulty in realising returns for its equity.

Overall, central PSUs’ share in total market capitalisation has more than halved from 15.9 per cent in March 2014 to 6.1 per cent in December 2020.

The number of PSUs increased from 39 to 54 in the same period.

As a result, the job of Department of Investment and Public Asset Management (DIPAM) has become even more challenging.

To deal with these anomalies, the government has mandated that PSUs outline a plan to monetise non-core assets and pay the government an assured sum as dividend.

These have been made a part of the memorandums of understanding PSUs sign with the government.

But can PSUs, by themselves, do much?

D K Srivastava, chief policy adviser at EY India, said PSUs can work on increasing their market cap only to a limited extent.

“Even if operational efficiency is high and financials are robust, movement of markets and market cap depends on the global economic situation,” he said.

But the bigger problem is that PSU stocks are a victim of subdued investor sentiment owing to the perception that government directives or policy tweaks may not be in the interest of non-government shareholders.

“There is a need for PSUs to compete in the market and need for accountability of the company’s board,” said N R Bhanumurthy, vice chancellor at Bengaluru’s B R Ambedkar School of Economics (BASE) University.

Not just the companies, but the government should also bring market-friendly reforms for sectors in which these PSUs are involved, he added.

The demand for higher dividend pay-outs will also constrain PSUs’ capacity to improve their performance.

Earlier, PSUs were required to pay a minimum annual dividend of 5 per cent of their net worth or 30 per cent of profit after tax, whichever was higher.

Now they will have targets set for dividends they should pay the government every year.

Recently, DIPAM has also asked companies to transfer interim dividend to the government quarterly and half yearly from an annual payment arrangement at present.

This raises concerns that high dividend payout may impact PSUs’ capex cycles.

In FY20, about 55 PSUs paid a total equity dividend of around Rs 47,000 crore against their net profit of Rs 82,750 crore, translating to a pay-out ratio of 57 per cent.

In the past five years, these 55 listed PSUs cumulatively paid equity dividend worth Rs 2.75 trillion, against their cumulative net profit of Rs 3.85 trillion, which translates to a record pay-out of 71.5 per cent, Business Standard had earlier reported.

“The government has been invested in these PSUs over a long period of time and these investments have yielded minimal return due to operational inefficiencies.

"So, the government is justified in seeking a steady dividend, but it should not resort to high one-time dividends that can impact a company’s expansion plans,” Srivastava said.

But as Bhanumurthy pointed out, the finance ministry keeps writing to PSUs year after year to shell out more dividend, but companies keep ignoring the request stating they have planned expansion which have not been fully implemented.

In the current financial year, PSUs have the capital expenditure target of around Rs 6.7 trillion against Rs 7.1 trillion in the last financial year (which includes expenditure by Food Corporation of India).

Finally, PSUs have to outline a roadmap for asset monetisation and the efforts taken to realise value from idle non-core assets such as land and property.

But legal hurdles have stalled the plan for years.

To kick off sales of such assets, DIPAM had earlier classified PSU non-core assets as those that don’t have any pending disputes or those that can be quickly resolved.

It’s also soon going to announce an online bidding platform to sell PSU assets that are litigation-free.

State-owned firms have also been asked to settle long-pending disputes so that such land holdings can also be hived off.

The problem here is that land title changes and settling litigation would require close cooperation with state governments.

For instance, Scooters India, which will soon be shut, has land disputes with the Uttar Pradesh government for two land holdings which cannot be sold unless the dispute is settled.

“There’s nothing much the companies can do,” said Bhanumurthy.

These are issues for which solutions have been attempted by various governments in the past, but with limited success.

However, such an attempt would lead to less damage to public sector assets in future, he added.

EY’s Srivastava said there should be an active and aggressive plan to sell such assets that are under litigation and the central and state governments should form specialised teams to oversee this exercise.

Once assets are monetised, the PSUs can use the proceeds for their own expansion and to pay the government higher dividends.

© 2025

© 2025