The goods and services tax will level the playing field for different sectors of industry, including domestic manufacturing, says V S Krishnan.

Photograph: Rajesh Karkera/Rediff.com

If there is any measure that will strengthen the Make in India effort, especially in goods, it is the goods and services tax (GST).

There are a number of reasons why this is so: First, it is expected that the total incidence of duty on manufacturing (goods) will come down from the present level of 26.5 per cent (Centre: 14 per cent, state value-added tax: 12.5 per cent).

This will happen mainly through a more balanced sharing of the tax burden between the goods and the services sector.

Second, it will create a level playing field between imports and domestic manufacturing.

Today, the effective central excise duty rate on non-oil domestic manufacturing is nine per cent but the countervailing duty (CVD) neutralisation on the import side is only six per cent, creating a negative protection against domestic industry.

This will go away with the introduction of the GST with the phasing out of all exemptions, including CVD exemptions, and the same GST rate will apply to both imports and domestic manufacturing.

Third, today the general perception is that it is more profitable to trade than to manufacture.

An important reason for this is that the tax burden on trading is much less than on manufacturing, which is compounded by tax leakages in the trading segment of the value chain.

Concurrent taxation by the Centre and the states of the same taxable base from raw material to retail will facilitate better compliance verification.

This will create a level playing field between domestic manufacturing and trading.

Fourth, lower threshold limits for manufacturing under GST will prevent fragmentation of units.

Today, a number of medium and large units are masquerading as small units to avail of exemption benefits, because "small" is defined on the basis of turnover rather than ownership.

The GST will encourage small units to grow and reap the benefits of scale. Compliant units will benefit from a level playing field.

While the benefits outlined will help organised industry in India, the advantages of a larger common market would fortify these advantages.

The slogan of Make in India by "Making One India" coined in the chief economic advisor's GST report is apt.

The making of "One India" is the making of one common market by eliminating inter-state taxes.

These include the central sales tax, entry tax not in lieu of octroi and entry tax in lieu of octroi. The benefits will lower logistics costs.

For example, one study shows that trucks in India in one day drive just one third of the distance of trucks in the US (280 km vs 800 km).

Eliminating checkpoints and other entry barriers would facilitate faster movement of goods as roads are still the preferred mode of transportation in India. Industry can therefore keep inventory costs low by keeping inventory levels down.

The other less discussed advantage is the expansion of the market itself because of the lowering of inter-state barriers.

This has happened on the taxation front where procedural simplification like e-registration and e-payment of duty has improved tax collections at the lower end of the taxpayer segment. A historical parallel was the passing of the Interstate Commerce Act of 1887 in the United States. Under this, the federal government appointed a regulator to control the tariffs fixed by railway companies.

These companies had used their monopoly position to fix high rail tariffs that adversely affected small traders and small manufacturers, constricting the size of the market.

By lowering rail tariffs, this Act helped expand the size of the US market and to a large extent fuelled the economic boom in the last decade of the 19th century (1890-1900).

The same will happen in India where a market expansion will take place by lowering of inter-state entry barriers.

The GST will also help industry by easing the cost of doing business.

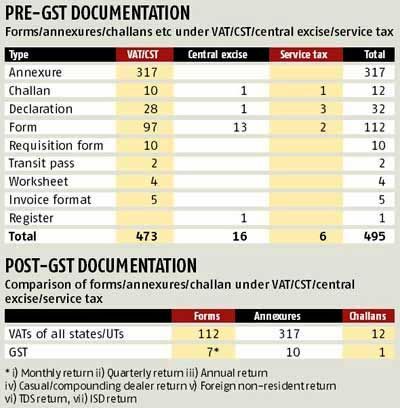

The information burden cast on industry today through multiple documentation and complexities is enormous.

The business process re-engineering done in the GST will obviate the need for paper documentation by completely relying on online information furnished in the registration and returns module by the taxpayer.

This procedural transformation is captured in the tables given alongside.

The greatest advantage of GST for the manufacturer is harmonisation of the best business practices not only between the Centre and the states but among the states too.

The GST will not only promote Make in India by "Making One India" but in the process also forge the bonds of fiscal federalism.

This will add one more dimension to the vision of cooperative federalism enshrined in our Constitution.

The author is retired member, Central Board of Excise and Customs.

© 2025

© 2025