It has been an eventful fortnight for global economies and markets, given the developments in Ukraine and Russia. India is going through a general election to elect a new government.

It has been an eventful fortnight for global economies and markets, given the developments in Ukraine and Russia. India is going through a general election to elect a new government.

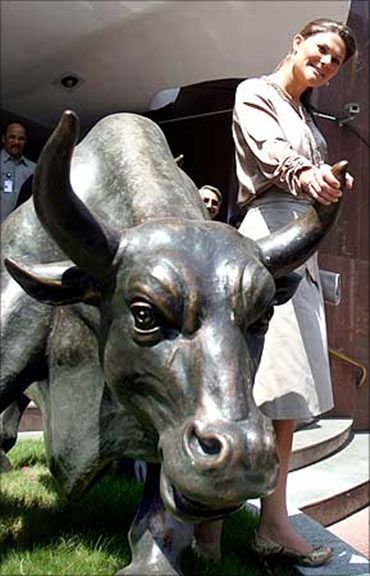

In this backdrop, Mark McFarland (Below left), global chief economist at Coutts, one of the world’s oldest banks, now wholly-owned by the Royal Bank of Scotland Group, talks to Puneet Wadhwa on these developments and why they remain overweight on India. Excerpts:

How do you see the key global economies shaping in the backdrop of geopolitical developments? Is there a cause for concern?

It is a cause for concern if one looks at Russia. The developments (there) have the potential to disrupt the flow of capital from the developed world to emerging markets (EMs).

A recent report from the International Monetary Fund suggests the Russian economy is in recession. What are the implications for the rest of the world?

Yes, the recession is already there. This will be a problem if Europeans are no longer able to access Russian gas. It will have implications for industrial growth in the second half of calendar year 2014 (CY14).

How do you see the European economy doing, especially Ukraine?

Provided everyone backs off, the European economy is recovering reasonably well. This implies as much to Eastern Europe as to Western Europe.

Between Russia, the United States and the European Union, if Russia is antagonised enough to cut supplies to Germany, this will have a material impact on Europe. Nearly half the gas in Europe is supplied by Russia.

What does it mean for oil and gas prices in the short to medium term?

We attach a 55 per cent probability that things will improve with Ukraine.

There is a 35 per cent chance of internal conflict in Ukraine and a 10 per cent chance of military intervention by Russia into Ukraine, that has the potential to become a military standoff between NATO and Russia.

In that case, oil and gas prices will rise significantly from current levels.

What are your readings for India within the EM, BRIC pack?

Among BRIC (Brazil, Russia, India and China) countries, China is slowing.

We see growth in China in the range of 6.75–7.25 per cent. Brazil is likely to experience slow growth of one to two per cent, despite investment in infrastructure ahead of the World Cup and the Olympics.

Their export sector will find it difficult to pick up momentum if there is a slowdown in China. Russia is now in a recession.

Given this backdrop, in India, even if one does not get the Narendra Modi-led National Democratic Alliance in power, there is enough evidence that the Indian economy is bottoming out and we are getting closer to the point where growth will start to accelerate and be around 5-5.5 per cent in 2015–16.

Our pecking order based on pure economic growth projections would be China, India, Brazil and Russia. However, based on pure preference, it would be India, China, Brazil and Russia.

As regards India, all hopes are high on a pro-reform, pro-business party coming into power post May 16. How are you approaching India now as an investment destination?

As regards India, all hopes are high on a pro-reform, pro-business party coming into power post May 16. How are you approaching India now as an investment destination?

We remain overweight on India. We think the banking sector is strong enough to withstand shocks. The industrial sector should pick up, given the global growth, especially cyclicals. This is a good reason to be optimistic about the equity market.

What is the broad view of foreign investors when they look at India now?

Non-resident Indians (NRIs) are very positive about India. NRI businessmen in Asia would like to put more money into India, if there is a strong and a stable government at the Centre led by Narendra Modi.

So, what is the incremental flow that could come in if Modi wins and is able to form a stable government?

It is difficult to put a number to it. However, the overall mood is positive and there is willingness to put in more money into India if that happens.

What if it is a fractured mandate? Would it change your investment strategy significantly, in the light of how economic and business policies play out?

Yes, it could change our strategy significantly. Indian markets are expensive. Investment in India has been very poor. The banks still have reasonably high non-performing assets (NPAs). So, there are some concerns.

© 2025

© 2025