'...Unless we muck up our policies.'

'We have to become a modernised economy.'

'Our institutions should be stronger. And that is most important.'

'The rule of law should prevail and contracts should be enforced.'

'Above all, we have to recognise the importance of globalisation.'

'It is in our favour at this stage. We should grow and become globally competitive.'

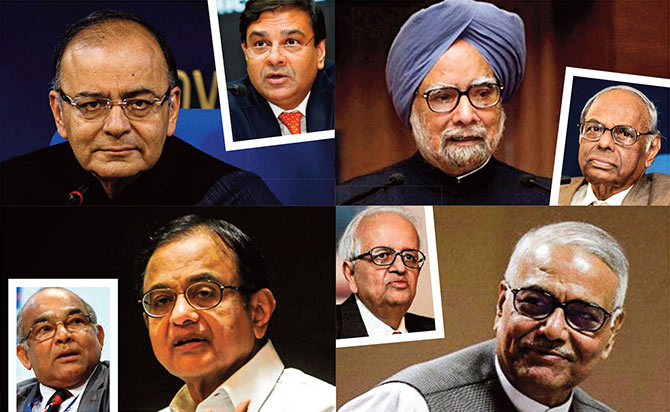

Clockwise from above left: former RBI governor Y V Reddy; Finance Minister Arun Jaitley; RBI Governor Dr Urjit Patel; former prime minister/former finance minister/former RBI governor Dr Manmohan Singh; former RBI governor Dr C Rangarajan; former finance minister Yashwant Sinha; former RBI governor Bimal Jalan; former finance minister P Chidambaram.

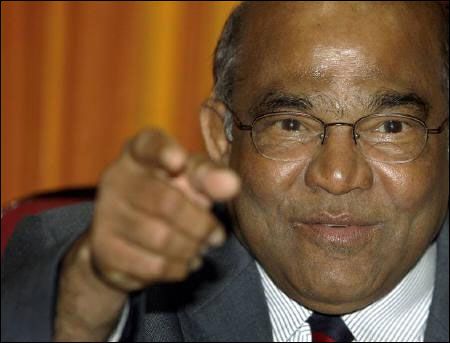

Former Reserve Bank of India governor Y V Reddy's memoirs, written in his mother tongue Telugu, provide insights into the dynamic relations between the finance ministry, for which he had worked earlier, when he was in the Indian Administrative Service, and the central bank.

In an interview to B Dasarath Reddy, he speaks of his insights into the workings of the financial system, as well as his experience of crisis situations, domestic and global.

After reading your memoirs, one is curious to know how different and how difficult three situations were: The balance of payment crisis in 1991, the 1997 Asian financial crisis and the global financial crisis that erupted in 2007.

The crisis of 1991 happened when the Indian economy was vulnerable to crisis.

The crisis was essentially a result of our own weaknesses, but was triggered by a global event, the Gulf crisis (the first Gulf war).

My role was at a middle level. For three years, from 1990 to 1993, there were three prime ministers, three finance ministers, three RBI governors and three finance secretaries.

I was handling BoPs. That was the best training ground for me. It taught me why the crisis had happened, how bad the situation can be if you take risks, and how policies can be reformed.

When the East Asian contagion happened during 1996-1997, India was fairly strong. We did not have to do much except taking action in advance to avert the contagion.

That was what we did in the famous Goa speech (delivered by Y V Reddy as deputy RBI governor) on exchange rates. Some impact was unavoidable.

There, too, I was the continuing factor between the beginning and the end of the crisis.

Rangarajan (then RBI governor Dr C Rangarajan) was in the initial phase of the crisis and then came Jalan (Bimal Jalan).

That gave me opportunities to learn about handling a crisis, reducing the impact of the crisis, which showed up in the foreign exchange markets, and studying the styles of the two governors.

With this education, I went to the IMF (International Monetary Fund) in 2002 for about a year.

As I was on the board of the IMF, I had seen countries like Turkey, Brazil and Argentina and learned of what happens if you have vulnerabilities.

So by the time I became RBI governor I was able to understand how domestic weaknesses and contagion can contribute to a crisis, and how the IMF can be helpful or not helpful, and to what extent.

All this made me understand the global developments and the domestic vulnerabilities.

So all I did as governor was to make sure that we don't take excessive risks.

No two sets of crises are exactly similar.

The banking and financial sectors were protected at the time of the global financial crisis as we took all the precautions.

But we had to have some problems since a bit of contagion is inevitable as we had opened up the economy.

In your memoirs, you are critical about the way economic growth was pursued in the run-up to the balance of payments crisis in 1991.

I was not exactly critical. The fact was that we were living, before the crisis, on borrowed time and borrowed money.

This is recorded in the volume on RBI history.

Manmohan Singh, in the 1991 Budget speech, records this in a sophisticated manner.

How different was the situation in the run-up to the global financial crisis?

In the first crisis, in 1991, there was a political leadership problem, and scarcity of forex.

The challenge from the Asian crisis was not that much.

In the run-up to the global crisis, the situation was very different and we were having too much forex.

We were having a problem opposite to the one in 1991.

The global ideology was emphasising financial deregulation. But we were trying to resist the excesses.

You were secretary, banking (in the finance ministry), and RBI governor, and have observed the relations between finance ministers and governors for many years.

Your insights would be of interest now since there is a debate going on over the question of these relations.

You are right. In some ways, I had the advantage of dealing with RBI officials when I was in the finance ministry as joint secretary and secretary, banking.

I had dealt with the ministry of finance when I was on the other side. That was at the official level.

But more important is that I was able to observe the relations between the finance minister and the governor.

When I was joint secretary, first it was Malhotra (the then RBI governor R N Malhotra), then came Venkitaramanan (then RBI governor S Venkitaramanan, who was finance secretary earlier), with whom I worked closely and was able to see how he interacted with then prime minister Chandrasekhar's government, then finance minister Yashwant Sinha and, later, then finance minister Manmohan Singh.

Later I observed how Rangarajan interacted with Singh as well as P Chidambaram, who was finance minister in 1996 to 1998.

As deputy governor I was able to observe how the governor interacts with the minister.

For instance, take Manmohan Singh. He was secretary in the ministry of finance and an RBI governor.

He knew the problems and therefore, the equation with Rangarajan was based on a very good understanding between the two.

And both are eminent economists.

Then we had Chidambaram, who was commerce minister before but had less exposure than Singh. But both Rangarajan and Chidambaram had certain professional elements.

In 1997, Jalan became governor. He was secretary, banking, and finance secretary too. Before that, he was chief economic advisor in the finance ministry.

Therefore, all the players had a long experience, they knew one another personally and they had worked with one another before.

I observed they had differences, but also trust in each other.

There were no ego problems. And the personalities were very different.

Singh talks very little. He is soft-spoken and knows so much.

His knowledge and pick-up are fantastic.

He is very calm and simple, and affectionate.

Singh makes everybody feel comfortable.

Rangarajan is totally a technocrat with a theoretical understanding and a vision.

He has all the qualities of a guru. Both of them cooperated with each other.

Even when there were differences, they fought them out. There was no bitterness.

Chidambaram is very sharp. And he reacts quickly. He understands quickly.

With Chidambaram, people are a little afraid because he is a little impatient and very quick.

But both of them (Dr Singh and Chidambaram) will dispose of files in no time. Nothing will be pending.

Sinha is solid because he was a bureaucrat before and has a political background.

He had worked in India and abroad and has tremendous common sense. He conducts himself with dignity.

He is not as quiet as Singh and not as active as Chidambaram.

Jalan and Sinha brought about more reforms as a team.

That is the best team we have had.

How do you view the recent controversy? Is it a matter of relations between the finance minister and the RBI governor?

I have no personal knowledge about it.

I know Finance Minister Arun Jaitley as a seasoned politician.

I know Governor Urjit Patel as an economist.

They have huge expertise and experience.

Therefore, I presume that there is no issue on the question of relations.

And every time, and on every issue, you cannot bring up the matter of independence because the RBI is a full-service central bank.

Now the RBI performs the functions of a debt manager.

If you are a debt manager to the Government of India, can you be independent of the Government of India?

You are an agent.

If you are handling monetary policy, then maybe the government should not be involved too much.

Recently you said that as an institution the identity of the RBI took a beating.

I am not heavily focused on any particular extraordinary event that is taking place, like demonetisation.

On the contrary, I am saying that when I look back on recent years, some element of undermining the identity of what the RBI should be doing should become a matter of concern.

It has been under threat in terms of what it has been before during my time.

That's why I wanted a national debate because the central bank is very important for the national financial security of the country.

When you became joint secretary, you were offered two options: To work in the BoPs (Balance of Payments) or in the banking division. You had chosen BoP.

In your memoirs you have said the decision was a turning point in your life and career.

Why did you decide to join BoP?

In 1987 and 1988 for two years I was on study leave.

I felt that our management of the economy and our understanding of planning, the State and the markets were inadequate.

So, in a way, I had this urge to understand the fundamental changes in economic policy.

That scope is less in handling IDBI or the banking department. There is more scope for macro policy in the BoP.

Therefore, I felt that there was an opportunity for me to use the understanding I had developed in those two years of leave.

Often I don't choose. It is destiny.

But destiny gave me a position.

Once I am in that position, I performed my dharma.

So destiny determines the boundaries and the framework in which I have to operate.

Every experience for me was learning.

One way or the other you had been associated with policy making continuously for 26 years.

In the next 10 to 15 years what kind of reforms and priorities would you like the government or the RBI to pursue to take India to the next level?

Compared to the past 20 years, the next 10 to 20 would put us in a different world.

Twenty years ago, we were struggling to get on to the world stage.

Today, India is firmly there. So, you can move with confidence.

Next, it is easy to come up to this level.

From this level to the next level of growth is very complex.

The institutions that we have developed -- the legal systems and parliamentary functioning -- have to be transformed now.

We have to become a modernised economy. It is not just information technology or only technology.

Our institutions should be stronger. And that is most important.

The rule of law should prevail and contracts should be enforced.

I believe that one of the things we neglected is public goods.

Public goods are those that cannot be provided by the private sector -- for instance, environment protection, public health, security, and law and order.

You have to give maximum emphasis.

But above all, now we have to recognise the importance of globalisation.

It is in our favour at this stage. We should grow and become globally competitive.

We have a greater stake in the global economy.

But we should not surrender the space needed to conduct our policies.

I would call the next 15 to 20 years India's decades unless we muck up our policies.

What kind of lessons can we draw from the demonetisation?

I am talking purely on an impressionistic basis. I think there has been a lot of pain for many people.

But also interesting is that people are willing to put up with the pain.

They did not complain as I expected.

What does it mean?

People feel that to get rid of black money and corruption they are prepared to go through the pain.

I think one result of this exercise is the demonstration of the intensity of dislike of black money and corruption by Indian society and the Indian people.

I am sure the politicians and political leadership have now understood that people are disgusted with corruption and black money.

They are prepared to put up with anything to get rid of it.

I think that's the psychological message.

You published your memoirs in Telugu first though you have the global audience.

How about potential readers of other regional languages?

I wrote my autobiography in Telugu because it is my mother tongue and I have my own sentiments for doing so.

It is a series of incidents and events that can be connected. And therefore, my feeling is that readers in other regional languages would be interested in its translation.

In India, we have got two types of markets for books. English is all over the country, but concentrated in three to four per cent of the people in Madras, Kolkata, Bombay and Delhi.

Regional languages are different. Their approach to issues is different.

If you (release) a book in English, it is usually read by one or two people.

If (you release it in) Telugu, it will be read by at least half a dozen people.

Very clearly I would like my Telugu autobiography to be translated into regional languages.

The English memoirs, which are technical and policy oriented, are meant for the global and English-reading audience.

c

© 2025

© 2025