'Here was a man (Rao) with no charisma. His party hated him. He ran a minority government in Parliament. For a man like that, to bring about the kind of transformation he did, there is no parallel in world history. There is no other reformer in the world who has achieved this much with so little.'

'Rao was capable of changing his mind very quickly.'

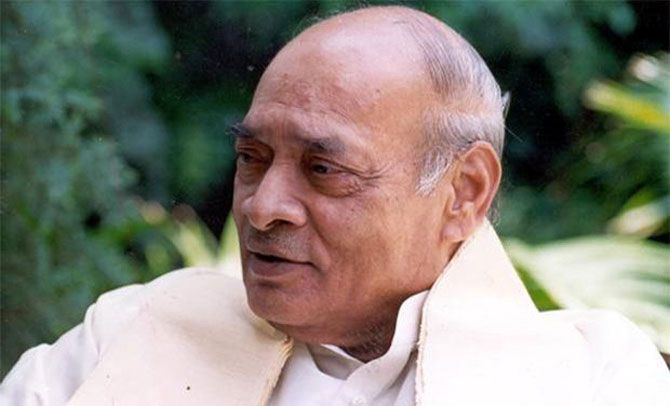

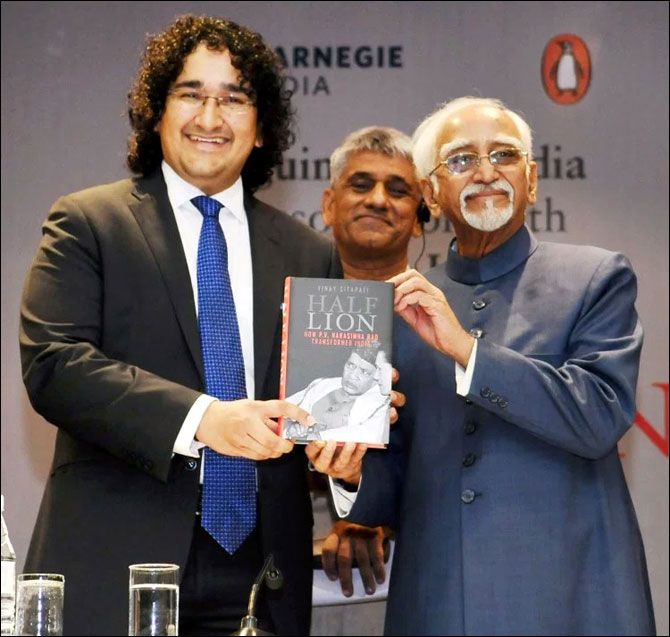

As India approaches the 25th anniversary of the reforms initiated by the Congress government in 1991, political scientist Vinay Sitapati, bottom, left, explores the role played by the then Prime Minister P V Narasimha Rao in steering the reforms through in his new book Half Lion. In an interview to Ishan Bakshi, Sitapati, who has access to Rao’s private notes, talks about the transformation of Rao from a protectionist to a believer as well as the opposition he faced in trying to get the reforms through. Excerpts:

Your book suggests Narasimha Rao was a protectionist to begin with. What brought about his transformation to a reformer?

In many areas such as foreign policy, welfare schemes and internal security, Rao changed from a socialist to a pragmatist.

But when it came to the economy, Rao surprised me. For instance, in the 1990 when he was in the Opposition, he wrote seeking protectionist measures to the then Commerce Minister Subramaninan Swamy.

But two days before he became the prime minister, he was handed a document by Naresh Chandra. That document was prepared by the line secretaries in the previous government. It highlighted exactly what reforms were needed.

His actions the day after showed he had changed his mind. And, it was manifested not just in the appointment of Manmohan Singh. Rao also wanted a principal secretary who was pro-market. He also promoted free marketers.

Rao was capable of changing his mind very quickly. There are examples in his life where he had this sense of the arc of history. When the time for change came, he could change very fast.

Did this pragmatic streak survive? You seem to suggest that he turned his back on reforms before the elections of 1996...

One must remember that by February 1992, the crisis was over. So, why continue with the reforms? That’s not pragmatism. All the big reforms we talk about in terms of implementation - opening up of consumer goods, FIIs (foreign institutional investors) entering the market, opening up of airlines, telecom, infrastructure - happened after 1992.

I think he became a believer. There is no other explanation.

But, I also think Rao realised early on that while liberalisation was important, it did not have a political constituency. It had a lot of political opponents.

In my judgment, Rao did not sell reforms. In the 1996 elections, he campaigned on the plank of welfare schemes because the beneficiaries of liberalisation only come in later. They did not exist then. Also, remember that Rao had a weak mandate. He could not take on that risk.

That is the central puzzle of this book.

Here was a man with no charisma. His party hated him. He ran a minority government in Parliament. For a man like that, to bring about the kind of transformation he did, there is no parallel in world history. There is no other reformer in the world who has achieved this much with so little.

The puzzle is why have subsequent reformers followed this step. In that sense, Narendra Modi is the first PM to have made a departure from the path of reform by stealth.

There are those who think that Manmohan Singh deserves more credit for the reforms and that Rao isn't the father of reforms...

The problem that Rao faced was that each of these changes was politically unpopular. They were unpopular with his party, big business, left intellectuals and trade unions. So, Rao tried his best to erase his fingerprints.

One of the reasons why many people say it’s not Rao who is the father of liberalisation is Rao himself. He realised because reforms were unpopular, the only way you can do it is by stealth.

I went through the records of numerous CWC (Congress Working Committee) meeting where Congressmen were shouting that liberalisation was anti-Nehru, anti-socialism etc. But, Rao simply said: ‘Why are you shouting at me? Doctor saab is sitting over there. He is the one who is giving me the medicine.’

What about opposition from within the Congress party and industrialists?

The Congress party was the biggest opponent to reform. Of course, there were reformers like Manmohan Singh and P Chidambaram. But, they were a minority. The Congress was terrified that it was going against socialism. That it was going against Nehru and Indira Gandhi.

On industrialists, the evidence is clear that Rao was engaging with them. He had sent Amaranth Varma and PVRK Prasad to reassure industrialists. But, he did not accept their requests. The evidence is also clear that he understood the difference between the industry bodies. He made a conscious decision to give CII (Confederation of Indian Industry) a prominent display in Davos. This is the classic Rao. Talk to them, assure them but don’t let them stymie the process.

Photograph: PTI

© 2025

© 2025