Dining out with a chief minister is not to be taken lightly. It takes about three months to get matching dates, and on the appointed day there is a flurry of telephone calls to confirm the arrangements.

Dining out with a chief minister is not to be taken lightly. It takes about three months to get matching dates, and on the appointed day there is a flurry of telephone calls to confirm the arrangements.

When I reach the appointed hotel, there is already an advance guard of officials busy on their mobiles, tracking the arrival of the host (me) and the chief minister's movements.

Soon there is a buzz as half a dozen white Ambassadors and 'jeeps' turn into the driveway, with 'black cats' on running sideboards, and one car with the telltale poles that speak of an electronic jammer.

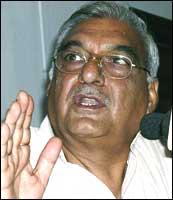

The cavalcade comes to a halt, the 'cats' rush up to a white Mercedes, rifles ready, and Bhupinder Singh Hooda steps out in his trade mark white. As everyone in the hotel porch gapes, I shake his hand and try to look inconspicuous.

After that statement of power and importance, the Haryana chief minister is refreshingly down to earth and unfussy. He poses for photographs without protest, the officials melt away, and my guest confesses that he would prefer to eat at home, is vegetarian, and the choice of restaurant is not very important to him.

I had offered a choice of three different cuisines, and his officials had got back with perhaps the inevitable choice: the Spice Route at the Imperial. I had asked for an inconspicuous table deep in the eatery's recesses, and since my guest settled very quickly for a fresh lime soda and the South East Asian equivalent of an Indian thali (something of everything), we were able to get down to talking without disturbance.

Hooda is not a household name outside his state. But he has a political legacy that almost matches the Gandhi clan's -- though on a more modest canvas. His grandfather fought an election on Moti Lal Nehru's Swaraj Party ticket back in the 1920s, lost and successfully filed an election petition to unseat his victorious opponent and take his place.

His grandfather was a close associate of Lala Lajpat Rai, and the family therefore belongs to the Arya Samaj tradition. Father Ranbir Singh has two unique distinctions: at 91, he is probably the only member of the Constituent Assembly who is still alive, having been elected to the constitution-making body when he was 33.

He went on to become a member of no fewer than seven different elected bodies, including the Constituent Assembly, the provisional Parliament, the first Lok Sabha, the Punjab Assembly, the Haryana Assembly and the Rajya Sabha, retiring from electoral politics in 1978.

Bhupinder himself is a four-term MP, and has been president of the Haryana PCC. And his son (27-year-old Deepinder), foreign educated and an ex-employee of Reliance, TCS and American Airlines, is now the new MP from Rohtak -- perhaps India's only fourth generation politician (not counting Sonia Gandhi!).

Most people don't realise how hard you have to work as a politician. It becomes obvious within minutes of our conversation that Hooda gets little time to sleep. His day starts between 6.30 a.m. and 7 a.m., and if he is lucky, ends the next day at 2 a.m., sometimes an hour later than that.

His immediate circle of officials doesn't have it much easier -- they have to keep him company after dinner as he settles down to clear files. The daylight hours, of course, are devoted to meeting constituency and state supporters at home, and then officials in the office, with further political meetings in the evening.

The other impressive thing about India's chief ministers is how capable most of them are, and how clearly they have thought through their priorities. Hooda has worked out that the world is coming to India; they have to come, therefore, to the capital city of Delhi; and if they come to Delhi they will come to Gurgaon.

But while the town has an international reputation, it has terrible infrastructure. Indeed, why think of just Gurgaon when 40 per cent of the National Capital Region falls within Haryana's boundary? The proximity to Delhi will therefore make Haryana's fortune -- if you can do the right things.

And so the chief minister has a five-pronged strategy:

- Develop infrastructure and most importantly power supply;

- Invest in road networks;

- Invest in education so that Haryanvis can man call centres (1.5 lakh people cross the Delhi border every day for work in the state, he says);

- Ensure law and order; and

- Provide one-stop clearance so that bureaucratic procedures do not impede investment.

And so there is mention of conversations with the Tatas for power, Mukesh Ambani for an SEZ package, NTPC for more power, and with various foreign universities for a 2,000-acre 'Rajiv Gandhi education city' north of Delhi which will (according to the chief minister) have some of the characteristics of Oxford.

Decrying the fact that many recent chief ministers of the state have not focussed on development, Hooda says he has already cleared a six-lane 135-km expressway linking the ring of Haryana towns that circle Delhi, so that none of them feels distant from the Gurgaon growth pole.

The numbers and programmes now roll out thick and fast:

- Rs 200,000 crore (Rs 2,000 billion) investment in seven years to create a million jobs,

- An innovative scheme to write off Rs 1,600 crore (Rs 16 billion) as old dues on power bills in phases if you pay future bills on time,

- Three or four specific incentives to prevent female foeticide in order to improve the abominable sex ratio in the state,

- A new industrial policy, and

- A programme for agricultural diversification and the building of cold chains so that agri-exports can be developed.

Where will all the money come from? That is not a problem, Hooda says. "Ask Montek Ahluwalia what he thinks of my action plan," he challenges. I check with someone else in the Planning Commission, and get a thumbs up.

We have reached the dessert, but Hooda is not very interested in the lichis with ice cream, and the tea that he asks for remains half-drunk. I decide lunch is over.

He walks out briskly, everyone jumps to attention, the convoy drives up, he is quickly into his Mercedes, and off to the noisy accompaniment of a police siren.

© 2025

© 2025