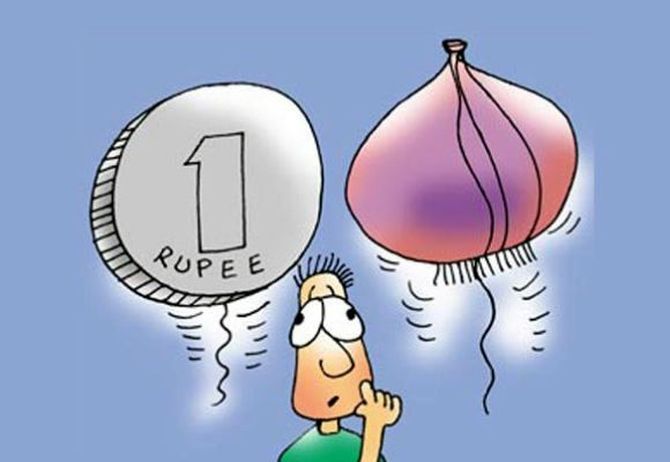

'Electronic media splash sensational headlines of the bulb prices about to cross the three-figure mark and focus on customers looking longingly at baskets full of onions, bemoaning their misery without this essential staple of their diet,' notes Shreekant Sambrani.

Illustration: Uttam Ghosh/Rediff.com

As surely as September follows August every year, onion prices shoot up come September.

Just as surely, the central government, regardless of its party affiliation or ideological leaning, takes a series of steps in quick succession: Raising minimum export prices, imposing stock limits on traders, banning exports altogether and announcing imports and their distribution at lower prices through public agencies.

Electronic media splash sensational headlines of the bulb prices about to cross the three-figure mark and focus on customers looking longingly at baskets full of onions, bemoaning their misery without this essential staple of their diet.

Those Delphic oracles, editorialists and sundry pundits, sombrely lambast the government's knee-jerk reactions and express grave concern for the lot of poor onion growers.

They assert that the only way out comprises a completely free trade, control of intermediaries (oblivious of the inherent contradiction between the two) and cold storage and processing, respectively to extend shelf-life and even out seasonal price fluctuations.

In November, shining new red onions reach markets by the truck-loads, prices decline and all is well again.

Until next September, that is.

Let us call this suite of rhapsodic movements 'The (Onion) Rite of Fall' (pun intended).

The chief reason for this cycle is seasonality of onion production.

September is towards the fag end of the stored crop reaching the market, and November is the beginning of the arrival of the new crop.

That understandable phenomenon has long been in evidence.

It is now compounded by weather-related occurrences, especially in the last decade, such as delayed sowing due to inadequate precipitation (the case last year) or loss of early planting due to floods, as has happened this year.

It has taken its toll politically.

Sushma Swaraj's tenure as Delhi chief minister in 1998 was chopped due to the price of the pesky bulb reaching the then unheard-of level of Rs 60/kg.

Her successor Sheila Dikshit very nearly suffered the same fate 15 years later.

This makes rising onion prices politically an extremely sensitive issue.

Unfortunately, both the perception and prescriptions offered are shrouded in myths, which need to be deconstructed to know one's onions.

First, the cost of production. Farmers claim that when the wholesale price in the main market, Lasalgaon in Nashik district, falls to Rs 10/kg, even their costs are not met.

Ashok Gulati and Harsh Wardhan cite a cost of Rs 9 to 10 per kg in Maharashtra as estimated by the National Horticulture Research and Development Foundation (The Indian Express, September 30, 2019).

The average price in Lasalgaon from January 2016 to May 2019 was Rs 9.92/kg, according to Harish Damodaran, who added that it just barely covered the cost of production of Rs 8 or so (The Indian Express, September, 30, 2019).

Does this mean that the otherwise very active and vocal onion farmers continued to grow and sell larger crops at barely cash break-even prices for three long years?

Very unlikely. A close friend, an educated and enlightened onion farmer in Satara for over 50 years, has immaculate records.

He estimated his total paid out costs to be Rs 85,000 per hectare last year.

He uses hired labour for all his operations, so this is the A2+FL cost as defined by the Swaminathan Commission.

Add to it the imputed fixed cost (depreciation, land rent and interest) of about Rs 12,000 to arrive at the full C2 cost of Rs 97,000.

This matches well (after adjustment for inflation) the full cost of Rs 67,000 per hectare in 2011 deduced from a survey of growers in the same district, as published in The International Journal of Agriculture Science (external link).

My friend's yield is 30 tonnes/hectare, so the cost of production is Rs 3.20/kg.

Even if the average productivity is lower, say about 20 tonnes/hectare, the cost would be Rs 4.80/kg.

At Rs 9.92/kg, farmers got more than twice the full cost of production, yielding a very attractive net profit of over Rs 1 lakh/hectare for a three-month crop.

Onion prices shoot up because of high storage losses.

The Indian Council of Agriculture Research estimates these to be between 40% and 50% when stored in ventilated, ambient conditions.

That cost is to the traders's account and gets added to the margin, which appears large and against the farmer.

But if we look at the farm and retail prices at any given time (not averaged over a year) the spread is reasonable, between 20% and 30%.

That covers transport and mandi taxes as well.

Modern retailing has, in fact, a larger spread than traditional markets for most vegetables including onions and I have come to the conclusion that a breakdown of competitive markets is the root cause of vegflation. That is the reality.

Dehydration and cold storage are non-starters.

India demands fresh vegetables, not processed stuff.

Conventional cold storage at 0°C leaves onions sprouting and covered in black mould.

Not much is yet known about ICAR's new cold storage technique.

So where does that leave us, after we peel all these layers of the onion enigma?

Exactly where we started, no wiser, and also unable to grin and bear it, because onions cause tears, literally!

Shreekant Sambrani is an economist.

© 2025

© 2025