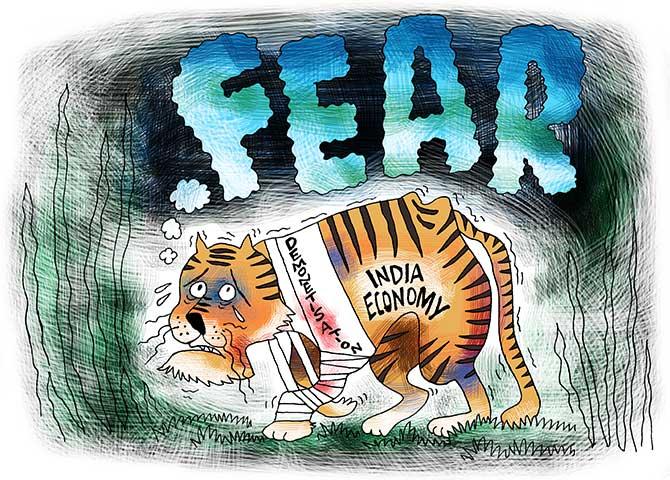

'India Inc has been afraid to criticise the government of the day for many years now, and it is perhaps unfair to blame the current one alone,' says Shyamal Majumdar.

Rahul Bajaj's comments recently that India Inc is afraid to criticise the government has kicked up a storm.

The most meaningless reactions have come from the government itself, with several senior ministers accusing Mr Bajaj of weaving 'fake narratives' and hurling 'invectives' at the Modi government.

While one said statements like this hurt national interest, a senior Bharatiya Janata Party member advised the industrialist to 'wear your political affiliation on your sleeve and don't hide behind inanities like there is atmosphere of fear and all that.'

The ostensible reason for such outbursts was that Mr Bajaj said what he did to someone no less than Amit Anilchandra Shah.

To his credit, the latter was quite restrained in his response.

Loyalty is a good virtue, but does one have to wear it on his/her sleeve all the time?

Had they exercised a little bit of judgement, it would have been clear to the ministers and the party office-bearers that every government in India has -- rightly or wrongly -- faced such accusations.

So instead of reacting so viciously, they could have debated internally how the trust factor could be improved with industry and bureaucrats.

After all, the current regime was supposed to be a 'government with a difference'.

On his part, if Mr Bajaj jogs his memory a bit, he will realise that the 'fear factor' or the trust deficit is nothing new.

India Inc has been afraid to criticise the government of the day for many years now, and it is perhaps unfair to blame the current one alone.

He would perhaps also remember what the late V P Singh did as finance minister in the Rajiv Gandhi government.

On a mission to unearth black money, Singh had launched a series of probes and raids against some of the most respected corporate groups.

Investigative agencies even raided the home of a respected industrialist like S L Kirloskar at midnight and detained him as if he were some petty criminal.

But there was hardly any braveheart in India Inc who spoke out against the witch-hunt at that time.

Former prime minister Manmohan Singh said the other day that economic development has stalled because of the 'profound fear and distrust among our various economic participants'.

This may well be true, but the fact is that the same thing can be said about the environment during the closing years of the United Progressive Alliance regime.

Mr Bajaj might have raised his voice a couple of times at that time too, but most others in his fraternity spoke only in hushed tones away from the cameras.

Investigative agencies, such as the Central Bureau of Investigation, have repeatedly come under the scrutiny of the highest court in the past for either being in league with the powers that be or not discharging their functions as required of them under the law.

Successive governments were also alleged to be quite active in browbeating their political opponents; in some cases, their allies; and select bureaucrats and industrialists.

As leader of the Opposition in the Rajya Sabha, the late Arun Jaitley had said with some justification that the comforting relationship between the political executive, CBI and the law officers had resulted in a travesty of justice during the UPA regime.

When Y S R Reddy was a tall Congress leader, the CBI looked the other way despite the enormity of his corruption.

When Y S Jagan Mohan Reddy parted company with the Congress, the CBI was let loose on him.

The following incident, of course, takes the cake.

As part of an investigation into illegal imports of foreign cars, the CBI raided the home of M K Stalin, the late M Karunanidhi's son.

The raid took place soon after the DMK pulled out of the UPA government.

Tellingly, the 'caged parrot' epithet was earned by the CBI during UPA rule.

In 2013, Justice B M Lodha also pulled up the then law minister for interfering with the agency in the coal block allocation case, and observed that the 'heart of the report' had been 'changed', ostensibly to favour the government.

The minister resigned following the expose.

Under the previous regime which now seeks to occupy a high moral ground, the CBI had booked industrialist Kumar Mangalam Birla and at least two former coal secretaries in the coal block allotment probe.

Former Securities and Exchange Board of India chief C B Bhave also went through turbulent weather after the CBI said it was looking into his conduct in clearing the application of MCX to set up a stock exchange.

The CBI had also moved against H C Gupta, who was the coal secretary between 2006 and 2009, and became a member of the Competition Commission of India after his retirement.

Because of the CCI post, the CBI had to seek permission from the ministry of corporate affairs to investigate Gupta.

After initially denying permission, the ministry gave its nod. Gupta had to resign from his CCI post.

The tradition continues even today.

But no purpose would be served by abusing those who speak out.

Going off the beaten track might be a better route to good governance.

Shyamal Mazumdar is a Business Standard columnist.

© 2025

© 2025