| « Back to article | Print this article |

Can there be a democratic polity without a culture of democratic behaviour? This may seem like a hackneyed question. But it has, once again, been brought into sharp focus in two very different contexts.

Can there be a democratic polity without a culture of democratic behaviour? This may seem like a hackneyed question. But it has, once again, been brought into sharp focus in two very different contexts.

One is the increasingly bitter dispute over the framing of a Lokpal Bill and the other is a film, Aarakshan.

Let us start with the film. When I went to see the film on Friday morning there were policemen posted outside the multiplex, in its lobby and inside the hall where the film was being screened.

The officer in charge indicated that similar security arrangements had been made across Mumbai. This is a preventive measure to deal with the threat of violent protests both by those who are pro-reservation and those who are anti-reservation.

The makers of the film have had to move the Supreme Court to ask for lifting a ban on the film imposed by the governments of Uttar Pradesh, Andhra Pradesh and Punjab.

This is after the director, Prakash Jha, reportedly agreed to make cuts to satisfy political leaders in Maharashtra.

This is the seventh film in the recent past that has failed to reach audiences in some parts of India because of protest about its content. Among the more famous of these cases are Jodha Akbar, which could not be screened in Rajasthan, and Fanaa, which could not be screened in Gujarat. My Name in Khan was not banned but it could only be screened after the central government ordered heavy police protection for cinemas in some cities.

In all these cases a film was opposed because it allegedly hurt the sentiments of some segment of society. Jodha Akbar was said to hurt Rajput sentiments. Fanaa was said to hurt Gujarati sentiments because the film's hero had supported the Narmada Bachao Andolan. Aaja Nachle was banned in Uttar Pradesh because one of its songs allegedly hurt Dalit sentiments.

The freedom to voice protest, when your feelings are hurt, is clearly an essential part of democratic culture. But when that protest takes the form of curbing other people's access to information, views, literature or cinema it undermines democratic culture.

Underlying such intolerance is a framing of issues in black and white terms. This is then accompanied by an unwillingness, or inability, to consider the grey areas in-between -- where most of real life actually takes shape.

Perhaps no other issue manifests this syndrome as sharply as the dispute over caste based reservations.

It is acutely ironic that the film Aarakshan has evoked such opposition from both sides of the dispute.

It is, above all, a moving account of people struggling to live their lives in the grey zone between the polar opposites of a pro or anti position on reservations.

The film's central characters are all pushed against the wall and forced to locate themselves in a black and white framing of the dispute.

Having suffered the loss of friendship and trust the characters struggle to find their way back into the grey zone -- where they find common cause in a fight for justice.

Those who are inclined to dismiss this as the idealistic license of fiction should reconsider that view. Yes, there are some situations in which we get locked into polarized positions.

But in many of the same situations a concerted effort to broaden the frame, venturing into the grey areas, can foster understanding where there was only anger and resentment.

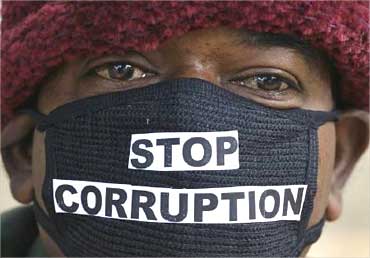

One such effort relates to the framing of the anti-corruption Lokpal Bill.

Aruna Roy, a leader of the National Campaign for People's Right to Information, has recently appealed for a de-polarization of the discourse around the Lokpal bill. In a widely circulated letter Roy laments that the intentions of those who critique the Lokpal Bill, drafted by the civil society team led by Anna Hazare, have been questioned.

"Critique of the Bill has evoked sharp reactions, and statements have been made that no amendments or change to the principles or the framework is possible, and that disagreement with the draft was tantamount to promoting corruption" writes Roy, who is also a member of the National Advisory Council.

Corruption itself is a black and white issue. It is wrong and ways have to be found to curb it. It is even understandable that those who are on the Joint Committee to draft a Lokpal Bill will feel that their version of the solution is the most workable.

But if they suggest that others who challenge their draft are 'soft' on corruption they might be over-simplifying the issue -- painting it in black and white terms. The details of the critique being offered by the National Campaign for People's Right to Information are not pertinent here.

This issue is referred to here because Roy is making a vital point when she says that the role of dissent must be placed squarely in the fulcrum of the debate: "The discussions after all, flow from the acceptance that a strong Lokpal Bill is needed. Also that the earlier and even the current government draft is faulty, even on principles."

Similarly, it is possible to be firmly committed to social justice, be supportive of measures like reservations to rectify historical disadvantages, and yet also have a incisive critique of existing reservation policies or how justice can be more effectively realised.

Demanding that we all fit into a black and white framing of any dispute undermines democratic culture.

Preventing others from seeing a film or reading a book -- because it depicts the grey realities of life -- is just one of various ways in which this is done.