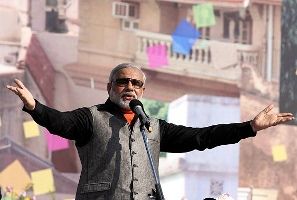

The NDA govt's economic policy differs from its predecessor's, says Abheek Barua.

A year after the heat and dust of an election has died down, the teething troubles of a new government (hopefully) abated and a slew of new policies announced, it is perhaps legitimate to ask two sets of questions of the elected incumbent.

A year after the heat and dust of an election has died down, the teething troubles of a new government (hopefully) abated and a slew of new policies announced, it is perhaps legitimate to ask two sets of questions of the elected incumbent.

First, what are its achievements on the ground? How many of the election promises have translated into concrete action?

One year of Modi sarkar: Complete coverage

The answer to this question has been debated by many analysts, including at least a couple of columnists in this paper.

The second set of questions that one might ask is whether the government has put its own stamp on public policy issues or simply mimicked its predecessor.

Let me begin with fiscal policy. After a period of an acute fiscal overrun between 2010 and 2013 that happened partly in a bid to fight the effects of a slowdown that followed the great financial crisis of 2008, the United Progressive Alliance (UPA)-II government made a desperate effort to rectify its image both with foreign investors and the international credit rating agencies.

Unfortunately, it indulged in what could be characterised as the most naïve caricature of fiscal fundamentalism - that of promising to produce a particular Budget deficit-to-national income ratio at any cost.

Little effort was made to raise issues of the state of the business cycle, its impact on tax collections and the myriad ramification of tightening expenditure too much in the middle of a major economic slowdown.

One year of Modi sarkar: Complete coverage

While the government's marksmanship in hitting the fiscal bullseye every year seemed perfect, the numerous fiddles that went into producing this number were all too clear.

Subsidy payments were delayed, critical capital spending was abandoned, tax refunds were pushed back, and so on and so forth.

Here's where Narendra Modi's government has made a clear departure from the earlier path.

The decision to target the fiscal deficit at 3.9 per cent of gross domestic product (GDP) instead of the 3.6 per cent (the milestone that the earlier government had set) seems part of a more mature dialogue with the community of investors and credit analysts that the government has chosen to initiate.

In a global macroeconomic situation where even the most doctrinaire of fiscal conservatives like the International Monetary Fund has emphasised the need for public investments, the need to create some fiscal space (without appearing to be reckless spendthrifts) was imperative.

Contrary to the apprehensions of many in the financial markets that this would irk the international rating agencies, their perception of India's fiscal situation seems to have improved.

This shift in our fiscal stand could buy more space, perhaps even a little more countercyclical fiscal action, if the economy fails to recover.

ADVERTISING

I would argue that the government's approach in trying to accelerate infrastructure projects also marks a deviation from the past. It is almost an axiom now that the government does not have the resources to fund India's humongous infra needs and private money has to come forth to fill the gap.

The question is: how should this private money be raised?

The much-touted private-public partnership model (that previous governments flogged) placed the onus of both building and financing a project on the private sector.

It has doddered along for years now without delivering much.

The new government's tack appears at least partly to take the execution risk on its books and bring more financial investors (rather than infrastructure builders) to the table.

This will take time - but, if implemented carefully, it could create a new and vibrant market for infrastructure project instruments that appeal to a different class of global financial investors (pension funds, multilateral agencies come to mind). I am, for instance, reasonably sanguine that there is considerable appetite for financial products that support railway projects.

The third departure from the past relates to the strategy for recapitalising public sector banks hobbled by non-performing loans and in desperate need for capital to meet their Basel-III needs.

Unlike the old approach, which was to resuscitate the weakest banks and let the more efficient ones fend for themselves, the tack going forward seems to be to bet on the more efficient ones and presumably allow for much-needed consolidation in the sector.

The very fact that state-owned banks are being pushed to the markets to meet their capital needs is a clear indication of this strategy - since, in the ruthless financial world, rewards are reserved for the efficient.

Besides, distressed banks can access the limited pot of money set aside in the Budget for recapitalisation only if they present a credible business plan.

In a political scenario in which - overwhelming election mandate or not - explicit privatisation remain politically sensitive, this might be the only way to rationalise the sector.

In its election rhetoric, the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) had made the sharp fall in the rupee's value a major issue.

One needs to commend the fact that its elected government appears to have climbed down from this stand and allowed the Reserve Bank of India and the markets to (at least partly) correct for inflation differentials.

For one thing, an overvalued rupee would have gone against the very idea of the "Make in India" campaign that seems at least in part to grow a global export hub in India.

The fact is that global demand is and will likely remain weak in the foreseeable future.

This is not to suggest that we do not need more clarity from the government on a number of issues.

My biggest concern is the rising share of bad loans in the banking system and the sooner we have a resolution mechanism where errant borrowers and lenders thrash out a deal, the better.

I am yet to see the nitty-gritty of either the "Make in India" campaign (in terms of ease of doing business) or the nuances of "cooperative federalism".

I find the term "big bang" abhorrent in the context of reforms - but could certainly do with more "aggressive incrementalism".

The writer is chief economist, HDFC Bank. These views are his own

© 2025

© 2025