'If you ask India's finest business leaders, they now tell you -- in whispers, of course -- that the mood has never been so glum after 1991,' says Shekhar Gupta.

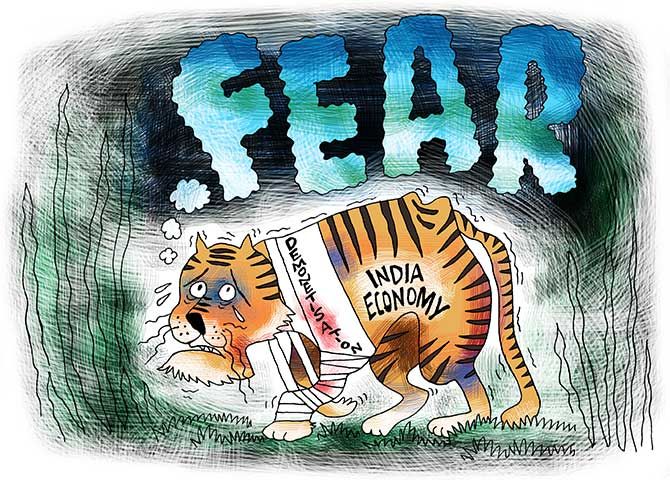

Illustration: Uttam Ghosh/Rediff.com

It isn't an expression our political class likes to use often, but there is talk every now and then to unleash the animal spirits of Indian entrepreneurship.

Manmohan Singh and later Jaswant Singh (as Atal Bihari Vajpayee's finance minister) are the only leaders we'd recall having appealed to these instincts from corporate India.

This Modi government too has tried lately to do so, in its own words.

In his Independence Day speech, Prime Minister Narendra Modi did some reaching out to India's 'wealth creators'. He said his government respected them and acknowledged that they also made an essential contribution to nation-building.

It was among the strongest endorsements of private enterprise by any Indian prime minister from the Red Fort. This has been followed by much other corrective action: Big corporate tax cuts, capital gains tax changes, and the reversal of that hare-brained idea to criminalise what some inspector might see as non-compliance by a company of its obligation to spend 2% of its profits 'correctly' on Corporate Social Responsibility.

Similarly, the egregious tax hit on capital gains of foreign portfolio investors was also withdrawn.

For a risk-loving government that never reversed a decision once taken, never blinked once it had decided to jump out of the back of the plane, without even bothering to check the parachute, these retreats were a new experience.

No one in the government would admit to it, but it has made to realise for the first time that there was something even the incredible personal popularity of the prime minister and the clout of his government riding its second majority cannot control: The markets.

The judiciary, media, Election Commission, even Pakistan can all be dealt with by a government of such power en passant. But the market isn't an animal political power can tame.

For the past many weeks now, Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman has been reaching out to the business community. She has unravelled some of the most problematic parts of her Budget on a press conference-by-press conference basis.

The finance secretary, who was probably key to the drafting of this 'bad news' Budget, was moved out and has since sought premature retirement.

Since the Budget, the RBI has carried out two quick rate cuts and generally spoken what the financial press describes as 'dovish' language.

Yet, there is little improvement in the mood, no uptick. No upbeat, smiling faces even at the World Economic Forum's India Economic Summit.

Animal spirits we are talking about? They are visible for sure. Just that the animal isn't what you wish it to be: A crouching tiger with its tail up. It is more like an abandoned puppy cowering with its tail between its legs.

If you don't like this metaphor, or abhor dogs, I can fall back on something more conventional, like a demoralised army. You can give one the best weapons, but if the generals are already defeated in their mind, they can't rally their troops into battle, forget winning a war.

This, the complete loss of morale -- even much self-esteem -- is the reason this flood of good news that the government has been unleashing, almost every Friday, is going down the drain.

The corporate tax break was a straight Rs 1.45 trillion impetus to Indian business. It led to a couple of days' rally on the markets. Since then, however, the larger reality has returned.

From the post-tax cut peak on September 24, companies just on the BSE's Sensex have lost a fresh Rs 2.53 trillion.

Other reversals and reforms, including interest rate cuts, have vanished in the same spate of pessimism.

The markets are not particularly in good odour globally in the post-Piketty world. But you have to acknowledge that however wayward, imperfect, or unequal they may be, they aren't afraid of speaking truth to power.

India's markets are fearlessly doing what many in the greater and more hallowed institutions like the media and even the judiciary are no longer willing to do: Give Modi government the bad news.

Last quarter's growth rate of 5% looked a shocker, but only to the innocent. Anybody keeping track of the economy would have expected this.

It is difficult to see it improving anytime soon unless something drastic is done.

What that can be, no one knows right now. Because if they did, at least among the circles where our fate is decided, the RBI would not have cut this year's growth forecast to 6.1% from 6.9%.

Entrepreneurship is driven not so much by profits or tax cuts today, but by optimism for tomorrow. That has been declining, especially since the first Modi government broke its own economic momentum with demonetisation.

Businesses are no different from ordinary people and families. When they see a bleak future, they fold all fresh incomes, savings, and bonanzas like the recent tax cuts into the family's savings for when times get worse.

It is only if they are upbeat that they invest in enterprise, and take risks.

Again, companies's capital expenditure data from CMIE will tell you the story. It was Rs 3.03 trillion in the quarter ended December 2018, came down to Rs 2.66 trillion by March this year, and then to a mere Rs 84,000 crore and Rs 99,000 crore in subsequent quarters.

Again, the CMIE data shows the latest quarter's sales growth for all companies has gone marginally in the negative to -1%.

The last time this happened was in the worst quarter of the Lehman crisis in 2008. This is not a slowdown. This is a rout.

You can cut and dice this data any which way, and the story is the same. All economic indicators, with no exception, are down and have been so for some time.

You can blame some of it on the global environment. But that is only a small part. The roots of the problem are here.

When almost all, including those like Mukesh Ambani, are sitting on cash, or de-leveraging and de-risking, repaying their loans and waiting, it is unfair to expect the rest to begin investing.

If you ask India's finest business leaders why, they now tell you -- in whispers, of course -- that the mood has never been so glum after 1991, and their self-esteem this low.

This comes not just with the weaponisation of tax authorities, with exaggerated and unfettered new powers of raids or arrest, but also the treatment of bad loans.

If everyone, from an ordinary individual borrower to a sincere entrepreneur genuinely struggling in a bad business cycle and a loan-thief are treated with equal suspicion and disdain, it leaves no incentive for entrepreneurs to borrow and for bankers to lend.

"All business involves risk," a prominent and respected corporate leader tells me, "but if I think even a 30-day delay in the repayment of my borrowing will have the bank publishing my name on the list of defaulters and referring me to the National Company Law Tribunal for bankruptcy, why would I risk it?"

"If a person falls sick, do you send him to the hospital or the shamshan ghat? This bankruptcy process under the latest RBI rules is the last rites of Indian entrepreneurship and a populist and revenge-seeking state has built us this shamshan ghat called NCLT."

The crisis in the economy is now beyond the pale of tax cuts, incentives, pep-talk, and promises. Some of these might work, but only fleetingly, like a shot of steroid or insulin.

India's economy now needs some genuine, brave reform. Maybe beginning with a big and genuine privatisation of PSUs.

If a Modi government won't do so even in its sixth year, it will only vindicate those who believe it has lost its reform mojo and is just an election-winning machine where growth is a desirable objective, but not essential.

By Special Arrangement with The Print.

© 2025

© 2025