Probably in August. We can argue whether RBI is dovishly neutral or neutrally dovish but the telltale signs of at least one more rate cut are strewn all over the policy statement, points out Tamal Bandyopadhyay.

Barring unforeseen developments (read: inflation overshooting the central bank's estimate or sudden growth impulse in the Indian economy), another round of rate cut is in the offing for sure.

The question is when.

Can it happen in June, at the Reserve Bank of India's rate-setting body's next meet? Or, in August?

My bet is on a August rate cut after the Union Budget (in July) is presented by a new government.

By that time, the monsoon will also be halfway through and the impact of El Nino on the Indian monsoon as well as on food prices will be known.

Why am I talking about yet another rate cut?

Hasn't the Indian central bank cut its policy rate in quick succession bringing it down from 6.5 per cent to 6 per cent between February and now?

Well, central bank watchers may quibble on the stance of the policy -- whether it's dovishly neutral or neutrally dovish -- the telltale signs of at least one more rate cut are strewn all over the Thursday statement of the RBI's monetary policy committee (MPC).

What are they?

-

The estimate of retail inflation is revised downwards to 2.4 per cent in the last quarter of fiscal year 2019; 2.9-3.0 per cent in the first quarter of 2020 and 3.5-3.8 per cent in the second quarter.

While the MPC doesn't see any "upside risks" to this estimate, and says the risks are "broadly balanced", most analysts feel the RBI is over-conservative in its estimate, the estimate could actually undershoot.

In February, the inflation target for the last quarter of 2019 was pegged at 2.8 per cent; 3.2-3.4 per cent for the first half of 2020 and 3.9 per cent for the third quarter.

-

Similarly, the GDP growth projection for 2020 has also been revised downwards -- 7.2 per cent (in the range of 6.8-7.1 per cent in the first half and 7.3-7.4 per cent in the second half).

Here too, the risks are "evenly balanced".

In February, the RBI had projected GDP growth for 2019-20 at 7.4 per cent (7.2-7.4 per cent in the first half and 7.5 per cent in the second half).

Since then, there are signs of domestic investment activity weakening; besides, the slowdown in the global economy will also impact India's exports.

-

Finally, the MPC observes that the output gap remains negative and the domestic economy is facing headwinds.

It also emphasises that "the need is to strengthen domestic growth impulses by spurring private investment which has remained sluggish".

Don't all these keep the door ajar for yet another rate cut? If indeed the retail inflation is contained at below 4 per cent, the real rate will high side if the policy rate is kept at 6 per cent.

The market, however, does not seem happy.

Bond yields rose (and prices dropped), local currency lost its value against dollar and most bank stocks as well as Bank Nifty, the representative index of the banking sector on the National Stock Exchange, fell.

The traders are upset because there has been no change in the stance of the policy; it remains "neutral".

Many were expecting it to be changed to "accommodative" and the greedy ones were even rooting for half a percentage point rate cut.

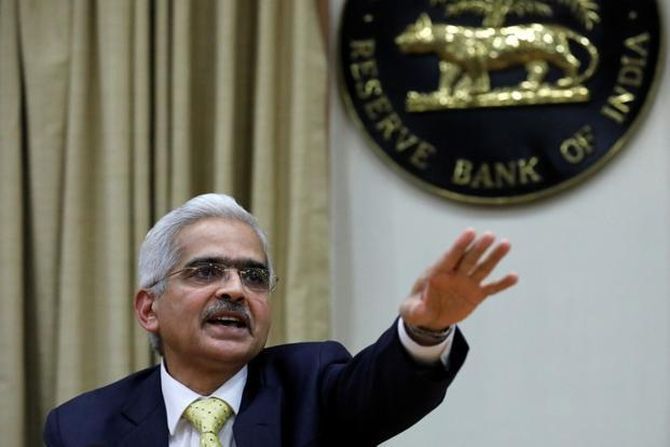

As was his wont, governor Shaktikanta Das had listened to all constituents of the market in the run-up to his second policy but he is not necessarily willing to say yes to all the suggestions.

The latest policy statement clearly shows he is maturing as India's chief money man.

For instance, the statement says, "the fiscal situation at the general government level requires careful monitoring".

There was no reference to India's fiscal situation in the February policy.

Also, at this MPC meeting there seems to be some concerns about the so-called core inflation or non-food, non-oil inflation, which was missing earlier (the focus was solely on headline inflation).

Theoretically, by keeping the stance unchanged at "neutral", the MPC has sent a message that its future course of action will be data-dependent and not made any commitment but the underlying bias cannot be missed.

The classic challenge before the RBI at this point is: It can lead a horse to water but can it make it drink? Even after another round of rate cut, as and when that happens, will the banks cut their lending rates?

Traditionally, Indian banks are miserly when it comes to passing on the benefit of low policy rate to the lenders and, of course, there are structural reasons behind this phenomenon.

Will Das, known for his consultative approach, be able to address this?

Finally, no prizes for guessing who voted for what at the MPC meeting.

It is becoming increasingly predictable.

Pami Dua, Ravindra Dholakia, Michael Patra and Das voted in favour of the decision to cut the policy repo rate by 25 basis points.

Chetan Ghate and Viral Acharya wanted the rate to be unchanged.

And, barring the eternal dove Dholakia, all others were in favour of maintaining the "neutral" stance of monetary policy.

Dholakia's choice was changing it to "accommodative".

Once-upon-a-time a hardcore inflation fighter Patra seems to be convinced that the inflation genie is bottled but, unlike Dholakia, he is not willing to let his guard down.

Tamal Bandyopadhyay, a consulting editor with Business Standard, is an author and senior adviser to Jana Small Finance Bank Ltd.

© 2025

© 2025