'A rag-tag coalition is more insecure and hence, more inclined to reform,' argues Devangshu Datta.

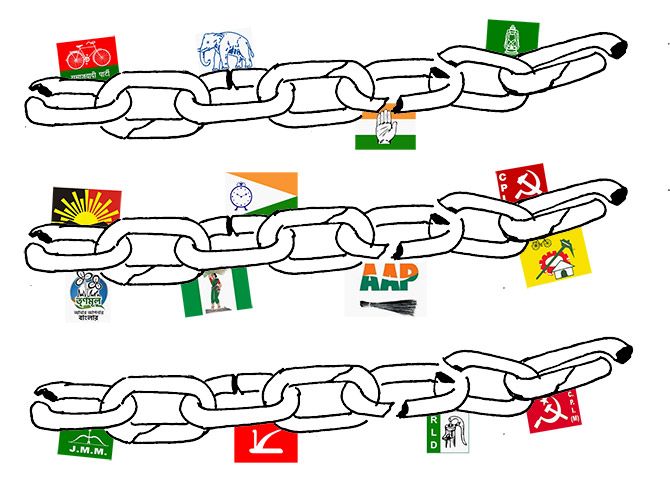

Illustration: Dominic Xavier/Rediff.com

If we examine economic policy down the years, the first great burst of reform and liberalisation came between 1991 and 1994.

The second phase came in 1999.

The third was between 2002 and 2005.

The first was driven by necessity with India's Balance of Payments perilously close to default, and economic growth down to near-zero.

It was carried through by a minority government at the mercy of strange bedfellows like the Left Front and the Jharkhand Mukti Morcha. That government was led by one of India's least charismatic politicians, P V Narasimha Rao.

Policy was re-conceptualised in its detail by a career bureaucrat turned finance minister, who later became another uncharismatic prime minister.

The second phase of reform in 1999 was carried through by a lame-duck government, which had actually lost a Vote of Confidence and started serving out its six-month tenure before it got started on reform.

That government was also under economic pressure because it had carried out nuclear tests and been hit by sanctions that severely affected trade. It was admittedly led by a man with some claims to charisma -- Atal Behari Vajpayee. But he consciously took a back seat as PM and let his friends, allies and party apparatchiks get on with policy-making and management.

Vajpayee's government also led the third burst of reforms in 2002-2005. In that stint, his government was supported by a bunch of regional allies, with their own pushes and pulls. The NDA included George Fernandes of the Samata Party, the Trinamool Congress, the AIADMK, the BSP, the TDP, the BJD, and sundry other examples of alphabet soup.

Each of these three phases of reforms proved to be sustainable. India turned a corner in the early 1990s. Nobody has yet tried to reverse the broad thrust of the reforms that started with the Rao government and continued through the Vajpayee years.

The longest, most sustained phase of growth came during the UPA years (2004 to 2013) when an uncharismatic PM led a coalition that was, to put it mildly, rainbow. In retrospect, Manmohan Singh did a fair job of guiding the economy through a global economic crisis of monstrous dimensions and tackling insanely high energy prices into the bargain.

Growth never faltered through that period while many other economies were derailed, first by the subprime affair and then by the Greek crisis that turned into the pan-European mess.

At first glance, it may seem paradoxical that tottering rag-tag coalitions led by uncharismatic individuals contributed so much. However, this is a feature, rather than a bug. Weak coalitions led by uncharismatic people are the ideal form of government for India.

One reason is that insecurity in itself sparks reform. Policy is made by politicians working in tandem with favoured bureaucrats (who may be retired and running so-called independent bodies, such as SEBI, or TRAI, or CERC, or the RBI).

The desi definition of liberalisation is all about the Babu-Neta nexus ceding control. If this nexus is insecure, it is more likely to ease controls (and probably take its cut), whereas if it believes it will be comfortably in charge for five years, it is more inclined to retain control and milk the economy.

A rag-tag coalition is more insecure and hence, more inclined to reform.

Reform also involves taking sane, pragmatic decisions that require careful implementation after a diligent review of processes.

Uncharismatic individuals are by temperament, more likely to think their way through situations, rather than relying on oratory and appeals to emotion. Charismatic individuals are more likely to make up meaningless but catchy acronyms, and talk stirring nonsense about "cashless" without thinking about either processes, or consequences.

Finally, coalitions that include a vast spread of regional parties actually represent India far better. Given India's socio-religious heterogeneity and vast differences in per capita across states, reforms carried out through coalition consensus appear more likely to be sustainable.

Ideally, this election will throw up a weak coalition and the individual leading it will be as uncharismatic and useful as a drain cleaner.

© 2025

© 2025