'If the current mood in North Block, headquarters of the finance ministry, is anything to go by, the government will now keep a closer watch on all kinds of schemes and projects undertaken by different central ministries.

'The next six months will determine which central schemes will have to be wound up and which ones will survive the axe,' says A K Bhattacharya.

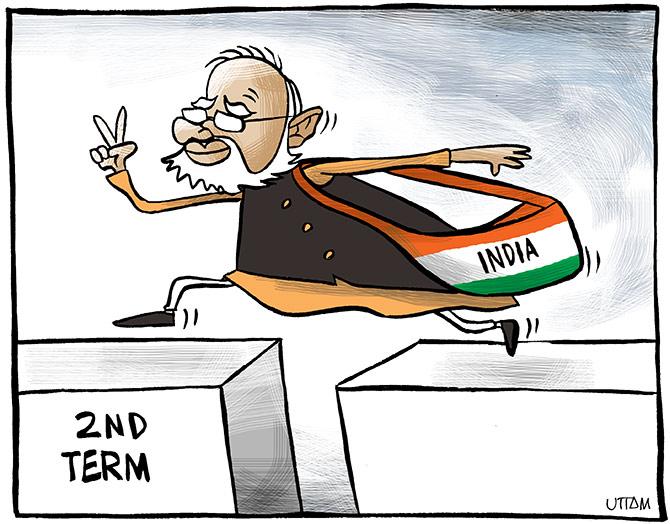

Illustration: Uttam Ghosh/Rediff.com

There is now a broad recognition within the government that its finances are tight and its ability to offer any fiscal stimulus or to increase expenditure is extremely limited.

This realisation will, therefore, influence the package of measures the government wishes to announce in the coming weeks to revive the economy.

The government’s unaudited provisional accounts for the first quarter of the current financial year show that its gross tax revenues grew by just 1.3 per cent over the same period of 2018-19.

This is woefully short of the full year’s gross tax revenue growth target of about 18 per cent, projected in the July Budget for 2019-20.

This comparison is based on the tax revenue collections in 2018-19 as per the provisional accounts, and not the revised estimates put out in the July Budget.

Hence, the growth figures reflect a more appropriate measure of the revenue efforts that will have to be made in the current year.

Thus, corporation tax collections in April-June 2019 were up by just 6 per cent.

The growth in revenues from individual income tax and customs duty, however, was slightly higher at 12 per cent and 16 per cent respectively.

The central goods and services tax recovered smartly in the first quarter by clocking a growth rate of 28 per cent.

But excise collections, which broadly indicate the consumption of petrol and diesel in the country and, therefore, the pace of economic activity, declined by close to 8 per cent.

This contraction is a cause for concern.

Not surprisingly, the government has applied the brakes on its expenditure.

Already, in the first three months of the current financial year, the government’s revenue expenditure has been reined in to grow by just 6 per cent.

This is much lower than the 22 per cent growth projected for the full year’s revenue expenditure.

A bigger squeeze has been applied on capital expenditure.

It was expected to grow by about 11 per cent in the full year of 2019-20.

But in the April-June period, capital expenditure has shrunk by over 27 per cent over what was spent in the same time of 2018-19.

If the current mood in North Block, headquarters of the finance ministry, is anything to go by, the government will now keep a closer watch on all kinds of schemes and projects undertaken by different central ministries.

An old circular on appraisal and approval of public-funded schemes and projects was uploaded on the website of the department of expenditure a few weeks ago.

Two directives of the notification stand out as they reveal its underlying objectives in no uncertain terms.

One, it bars all central ministries from taking up any new schemes or projects without obtaining a prior in-principle clearance from the department of expenditure.

This effectively rules out fresh expenditure on any new scheme that a minister or a secretary may like to implement under its administrative jurisdiction.

Simultaneously, the finance ministry has also asked the central ministries to actively consider merging, restructuring or dropping schemes or projects that have become redundant or ineffective.

What must be noted here is that while the in-principle clearance of the finance ministry has to be obtained for launching a new scheme, a closure or restructuring of redundant schemes could be initiated by any central ministry without obtaining North Block’s prior permission.

The second directive has important ramifications for the future of many schemes.

In 2016, the total number of central sector schemes were pruned to 300 and that exercise to streamline them further has been going on in the last three years.

Similarly, the number of centrally sponsored schemes with the Centre’s participation, was whittled down to just 30.

The first deadline for deciding on the future of such schemes after a review was March 2017, which coincided with the end of the 12th Five-year Plan.

The second and final deadline for completing such a review happens to be March 2020, when the applicability of the recommendations of the 14th Finance Commission will come to an end.

The finance ministry has just about six months at its disposal before it can ensure that all the remaining central sector projects and centrally sponsored schemes are reviewed to ascertain if they are redundant or have become ineffective.

The second directive reiterates that the sunset clause will be applied to all such schemes whose continuation cannot be justified beyond March 2020.

The argument is that the 15th Finance Commission’s recommendations would become effective from April 2020 and only those schemes, whose continuation can be justified on the ground of funds availability, can escape the sunset clause.

The next six months will determine which central schemes will have to be wound up and which ones will survive the axe.

Lobbying for and against these schemes will also become intense in the coming months.

© 2025

© 2025