| « Back to article | Print this article |

Signals received from the government in the past one year reflect a state of utter confusion, says Abhishek Tripathi.

The need for an electric vehicle (EV) revolution in India is far greater than, perhaps, in any other major economy of the world.

The levels of urban pollution and the contribution of oil to the current account deficit alone should force policy-makers to push for EV mobility.

While the technology is taking its course, an appropriate policy direction through government support and regulatory clarity can go a long way in quickening the pace of adoption of EVs in India.

Signals received from the government in the past one year reflect a state of utter confusion.

It started with ambitious claims to achieve 100 per cent EV mobility by 2030, which after some disquiet got rationalised to 30 per cent.

Much time was lost in determining whether provision of charging facilities for EVs amounts to sale of electricity or provision of service under the Electricity Act ("Act").

At last, good sense prevailed and it was held to be a provision of service, thus dispensing with the requirements of licensing under the Act.

The issue of subsidy to consumers purchasing EVs too has seen flip-flops, with consumers initially getting the subsidy under FAME (a central government scheme), which is now proposed to be made available only to cab aggregators.

At the macro level, an EV policy which outlines the road map for EV mobility and development of infrastructure would have helped in providing the necessary clarity to both manufacturers and consumers.

However, that too appears to have been shelved.

The latest reported statement from the government is that "India does not need an EV policy".

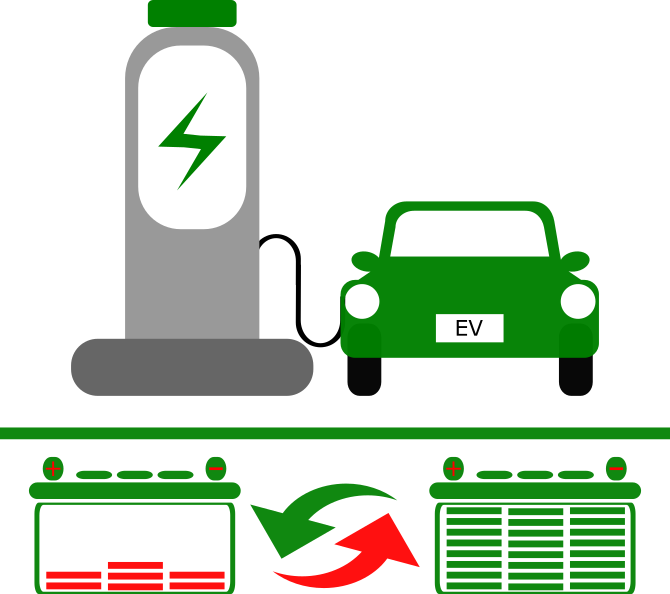

For EVs to be viable, an EV ecosystem needs to be created first.

The absence of charging infrastructure (CI), coupled with the short distances in which EVs can operate due to battery limitations, makes EVs a non-starter for many consumers.

Given current EV volumes, standalone CIs for any operator may not be viable without some kind of government support in the form of subsidies, viability gap funding (VGF) and incentives.

While it will be tempting for the government to pick one of its cash-rich PSUs, like NTPC, PGCIL, or even oil marketing companies to set up the CI, it will be prudent for the government not to restrict its purse to PSUs.

PSUs have little experience of operating such infrastructure, and being listed entities, it will be unfair to saddle them with such responsibility at the cost of shareholder value.

In addition, oil marketing companies, which can allow the setting up of CI at their fuel stations, will face considerable conflict of interest in promoting a technology that is likely to erode their own profitability.

Competitive and open bidding for VGF may prompt serious and experienced players to step in to set up CI.

The involvement of private players in a transparent bidding process in solar power projects has shown how quickly tariffs can be reduced.

Fair competition in EV charging may show similar results if all players are provided a level playing field.

Consistent supply of power to CI operators at a reasonable cost is another challenge.

While some electricity regulators have taken the initiative to establish a separate tariff category for EV charging stations, many others are yet to wake up to their existence.

The tariff charged to the charging stations needs to be reasonably low to ensure that EV users do not indulge in arbitrage by shifting the charging burden to their domestic connections.

Mass-scale charging of EVs through domestic connections, as against through commercial charging stations, may create problems for grid management and stability.

Further, to ensure consistent availability of electricity, pan-India open access for CI may be required in the long-term.

In the short run, the regulators may be persuaded to at least allow intra-state open access to enable CI operators to purchase electricity in the market within the state.

Open access has often been made unviable through cross-subsidy surcharge (CSS).

Given the broad policy objective of promoting EVs, EV operators should not be burdened with meeting the subsidy burden of rural and low-income customers.

Therefore, such open access will also need to be allowed at no CSS.

Wherever practicable, CI operators will also need to be incentivised to invest in captive generation units, and the regulators will need to ensure that CI operators are not subjected to excessive wheeling and banking charges.

The battle between EVs and conventional vehicles (CVs) is loaded in favor of the CV.

The cost, availability, and ease of driving alone make CVs the obvious choice.

The balance will need to tilt for EVs to become the preferred choice, and easy availability of charging infrastructure and battery swapping facilities will hold the key to shifting consumer preferences, at least in the short run.

Appropriate government intervention can make migration to EVs smoother and quicker.

Abhishek Tripathi is partner, Sarthak Advocates & Solicitors, a Delhi-based law firm.