One fine October morning nearly 36 years ago two young Indians landed up at the personnel department (now would be called HR) of the World Bank in Washington to sign on for the Bank's Young Professional Programme. One was Percy Mistry, the erstwhile chairman of the High Powered Expert Committee (HPEC) on developing Mumbai as an international financial centre (IFC). The other was me.

Percy and I have been friends since then, although our very different trajectories in life and geography have constrained the closeness of our friendship. I sincerely hope that the ensuing critical appraisal of the HPEC report will not strain our amity. However, knowing Percy's largeness of heart and mind, I am fairly sanguine on this score.

Percy is a no-nonsense sort of fellow. So I was not altogether surprised to learn that he had resigned the chairmanship of HPEC a few days before the report was submitted to the finance minister in early February. It certainly created a piquant, if not mysterious, situation.

According to the grapevine and the press, the final draft of the report had contained scathing references to the performance and problems of public sector banks (PSBs), which provoked the PSB bank chiefs on HPEC (who had been largely absent in earlier meetings of the committee) to demand alterations of the draft. Percy refused and quit. The report was diluted and submitted to the government. More on this later.

The HPEC report is a curious mixture of interesting analysis, some blatant financial sector boosterism, a few significant diagnostic weaknesses and a long and motley list of policy recommendations, including some sensible and some bizarre ones. Taking the positives first, the report provides very useful discussions and definitions of IFCs and IFS (international financial services).

It goes on to list key requirements for successful development of an IFC and notes that Mumbai possesses several of the necessary attributes, such as a fast growing hinterland generating expanding demand for IFS, good human capital, good location, democracy and rule of law, and quite well-developed securities markets.

On the flip side, the report identifies key gaps, which need to be filled if Mumbai is to successfully aspire to develop into a thriving IFC.

These include: weak financial governance, missing markets (such as for bonds and derivatives) and institutions (such as large international and domestic institutional investors) and the poor urban infrastructure of Mumbai. The report goes on to analyse these shortcomings in some detail and then presents a long and daunting list of policy prescriptions.

HPEC fails to make a clear and compelling case for the benefits flowing from nurturing Mumbai into an IFC. It asserts: "In sustaining its trajectory as an emerging, globally significant, continental economy, . . . India has no choice but to (a) become a producer and exporter of IFS; and (b) capture an increasing share of the rapidly growing global IFS market. To achieve these two goals, its financial centre in Mumbai must become a successful IFC."

This is simply an assertion, not the conclusion of a reasoned argument. It's also wrong. Just look at the striking development successes of East Asia and Southern Europe post-1960. Barring the city states of Singapore and Hong Kong, having (or developing) an IFC was not a "must" for the tremendously successful economic development trajectories of Korea, Malaysia, Taiwan, Thailand, China, Spain, Portugal and Greece.

The mere fact that India might purchase around $50 billion of IFS by 2015 (HPEC projections) constitutes no case for their local production. By then, India will quite likely be importing $800-1,000 billion of goods and services.

That's an outcome of healthy international specialisation and commerce, not a case for producing everything in India. There is no shame in importing sizable amounts of IFS, if India does not have a comparative advantage to produce or export them.

Perhaps the most obvious diagnostic soft-pedalling (dilution of the draft?) concerns the regulatory weakness stemming from the dominance of government-owned financial institutions. HPEC correctly observes "The quality and credibility of IFS provided from India is inextricably linked to the soundness and global acceptability of the regulatory/legal system that governs finance in India."

Yet, to take the most obvious example, banks constitute the biggest part of India's financial system and three-quarters of banking assets are in PSBs. How can the RBI seriously improve its regulation of PSBs when the owner (the government) outranks the regulator? And, one might add, frequently issues diktats to both the RBI and PSBs, not to mention packing PSB boards with political hacks.

The Mystery Report does contain gentle references to the need for "diminished public presence" and "reduced equity stake" of government. But there is no clarion call for tackling the 800lb gorilla in India's financial living room, which squats athwart the path of regulatory reform. Basically, without privatisation of PSBs and government insurance companies, the chances of developing an IFC in Mumbai are dim.

HPEC favours radical reforms in India's financial regulatory architecture, including "unifying all organized financial trading under SEBI regulation including currencies "

As a relatively young regulator, SEBI has done rather well in evolving stock market regulation. But extending its domain to currencies, commodity derivatives and so forth seems premature at best, and unwise, at worst. Given the RBI's much longer regulatory history and (unlike SEBI) trained cadres, a more pluralistic approach to regulatory architecture seems safer for the foreseeable future. Indeed, HPEC displays surprising insensitivity to the historical and contextual contours of financial regulation in India.

Another key diagnostic weakness of HPEC lies in blithely recommending rapid transition to full capital account convertibility (CAC), without adequately considering the implied loss of autonomy for India's exchange rate and monetary policies. HPEC shows little understanding of the nuances and benefits of an "intermediate" exchange rate regime of the kind that has served India well for over 15 years. Perhaps this is because the HPEC's composition was long on finance chiefs and short on policy economists.

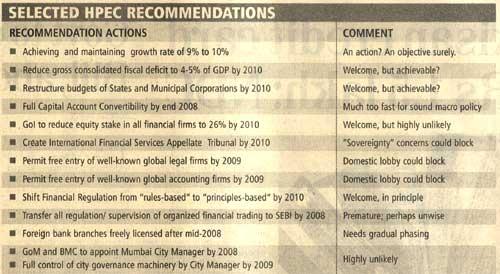

The Mystery Report lists 48 (!) "Recommended Actions" (mostly in the next two years) for paving the way for Mumbai's rise as an IFC. It's a wide-ranging and challenging list.

Given space constraints, I have listed a few of these in the table and added my telegraphic comment on each. I have omitted most of a long list of prescriptions to improve Mumbai as an urban centre (a worthy goal in itself).

With Maharashtra's power system in a shambles and brown-outs looming over Mumbai, the IFC vision seems distant. Indeed, after pondering HPEC's policy prescriptions I am inclined to conclude that the chances of Mumbai emerging as an IFC within a decade or so are somewhat less than my becoming a concert pianist (and I haven't started my lessons yet!).

The author is Honorary Professor at ICRIER and former Chief Economic Adviser to the Government of India. The views expressed are personal.

© 2025

© 2025