Neither the CAA nor the proposed NRC are important enough to stake the well-being of so many or stake economic growth.

Getting growth back on track is more important, notes Mahesh Vyas.

The labour participation rate (LPR) had fallen to an all-time low of 42.4 per cent in November 2019.

This, along with a host of other fast-frequency data, suggest that the Indian economy is likely slowing further in the third quarter of fiscal 2019-2020 after growth dropped to 5 per cent and then 4.5 per cent in the first and second quarters respectively.

Preliminary and partial data for December indicate that labour participation is recovering from the November fall, but perhaps, not enough to make November look like an aberration.

The LPR has scaled up in each of the three weeks of December.

In the last week of November, the LPR was 42.21 per cent.

Since then it has inched up progressively -- initially to 42.72 per cent, then 43.08 per cent and then to 43.24 per cent in the week ended December 22.

The average LPR during the first three weeks of December was 43.01 per cent.

The 30-day moving average of the LPR was 42.87 per cent.

The LPR, which was falling for several years, had stopped its decline about a year ago.

Over the past year, the LPR has mostly been range-bound between 42.5 per cent and 43 per cent.

In recent months it had displayed a little tendency to rise above 43 per cent.

August, September and October 2019 had seen the LPR remain persistently above the 43 per cent line.

42.5 per cent was a redline of sorts.

But this was breached in November.

In December, the LPR could climb out of that redline and may reach the 43 per cent mark.

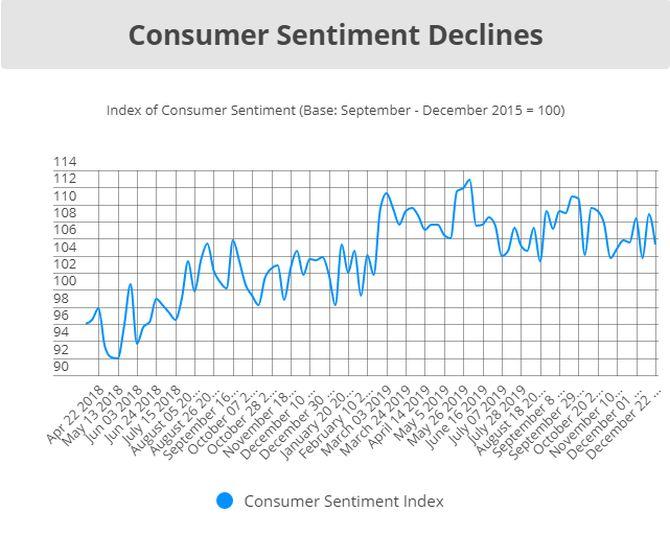

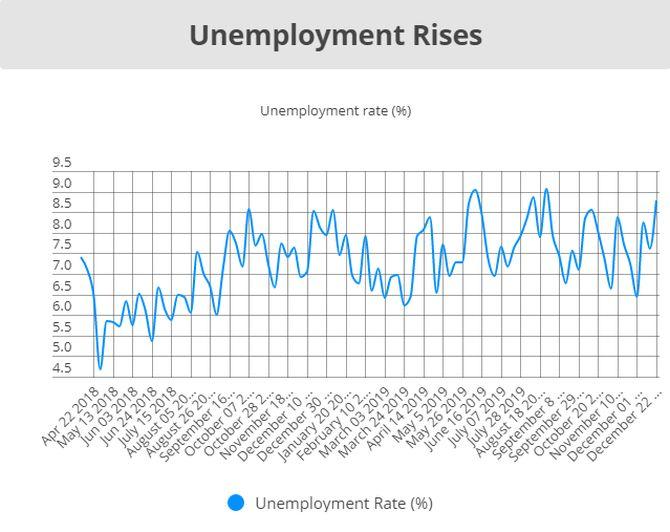

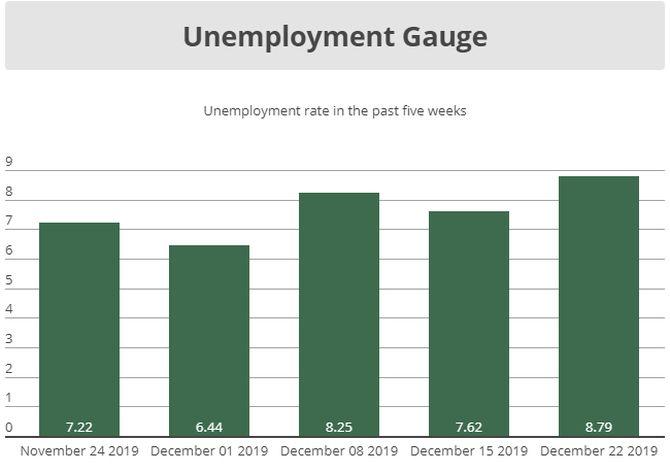

However, this increase in the LPR is likely to be accompanied by an increase in the unemployment rate.

This averaged 8.22 per cent in the first three weeks of December compared to the 7.5 per cent pencilled in November 2019.

The unemployment rate is sensitive to the labour participation rate.

If the labour participation rate rises, unemployment also rises.

This indicates that the Indian economy is not able to provide jobs to the additional flow of labour into the labour markets.

Demand for labour in December seems to be facing two major problems.

First, the economy is slowing down.

Power generation was down by 12 per cent in October and down again by 6 per cent in November.

Industrial production has been falling too.

Automobiles and real estate are witnessing a protracted slowdown and, the kharif crop was partly but significantly damaged because of late rains.

If the economic activity slowed down further in December or even it continued to remain weak, it is expected that the demand for labour would have been adversely impacted correspondingly.

Any increase in labour participation rate will therefore lead to a higher unemployment rate.

Second, strains in the social fabric are likely to be impacting the demand for labour in places where the tensions have spilled over into the streets.

The continued effective lockdown in Kashmir puts out an estimated four million out of the labour force.

Or, it constrains their effective participation in the labour force.

Elsewhere in India, where law and order is disturbed, daily wage earners, small traders and street vendors are immediately pushed out of the labour markets.

According to CMIE's Consumer Pyramids Household Survey, there are an estimated 88 million small traders, hawkers, street vendors and daily wage earners in India.

They account for about 20 per cent of the total labour force and 22 per cent of all employed persons.

These are the vulnerable people.

Social unrest spread through scores of towns in December.

These witnessed imposition of restrictions on assembly and in some cases even limited curfew.

In such places around 20 per cent of the workforce is immediately pushed out of the labour markets.

An equally vulnerable set is the 14 per cent self-employed entrepreneurs.

These are shop keepers, taxi drivers, self-run barber shops, self-run gymnasiums, beauticians, tourist guides and the like.

While the daily wage earners and street hawkers lose wages during civilian strife, self-employed entrepreneurs run the risk of loss of property during such times.

The impact of social strife on factory workers and office goers is also increasing because the proportion of contractual workers in total employment is increasing.

Often, payments to contractual workers are subject to attendance or even output.

A fragile economy can ill-afford the social strife that has spread across Indian states.

The relatively vulnerable sections of society -- small traders, vendors, daily wage earners -- cannot afford the effects of this strife on their economic well-being.

Neither the Citizenship (Amendment) Act approved by Parliament nor the proposed National Register of Citizens are important enough to stake the well-being of so many or stake economic growth.

Getting growth back on track is more important.

Growth generates employment for those who are willing to work.

And, good employment for those who are willing to work can motivate more to join the Indian labour force to seek employment.

India needs more hands to the till to accelerate growth to reach its cherished target of becoming a $5 trillion economy.

Staying focused on this target may be a good strategy.

Even a partial failure in achieving this target may be better than the distractions around determination of citizenship.

Mahesh Vyas is the MD & CEO, CMIE

© 2025

© 2025