| « Back to article | Print this article |

Travel tales: The most amazing stories from UP to Italy

Kushal Chowdhury travels down memory lane and comes up with stories he heard - some real, some unreal - that amused him.

Some months ago, I travelled through the innards of Uttar Pradesh for two weeks on an official trip, meeting distributors and retailers, and talking shop and Sunny Leone with them (as important a sales tool as excel sheets and channel margins and incentive schemes).

It was a rather uneventful trip, filled with inane conversations and congested two-lane highways, but there is one particular conversation that I remember clearly -- a conversation the likes of which make otherwise dour trips such as these worth it -- with a relatively insignificant distributor tucked away in a non-descript village on the highway between Gorakhpur and Banaras, and his father.

We met in his house, a large single-storey building, terribly designed, aesthetically speaking -- surrounded by open fields and yet very little sunlight in the nearly dozen rooms, and too many doors opening directly onto the front porch -- but of course, like with most such houses -- the crown jewel of a family man’s lifetime of labour -- the intent in design has little to do with aesthetics and everything to do with the number of offspring and succession and the absurd fantasies of parents in which there not only exist forever after them but also one in which every subsequent generation lives happily together.

We sat on a charpai laid out on the porch -- it was just after a spell of rain and there was a gorgeous breeze -- and chatted over cups of tea; the father reclined on a separate charpai and scratched and coughed and belched and interjected once in a while with anecdotes from when he was younger.

He spoke of a time when they were close to the Yadavs, pausing for emphasis at the name, so as to leave little doubt which Yadavs he referred to, before continuing with his story (not a particularly interesting one). I looked at his face searching for a reason to disbelieve him and found none.

Outlandish as some of these stories and claim seem at first, I have learned from experience that there are often degrees of truth hidden in them. I met a real estate broker in Delhi once, who confided in me that he used to work with a jewellery shop in Mumbai and smuggled ornaments and such to Lucknow. There was a lot of money in it, he explained, far more than in real estate broking.

I asked him why he’d stopped then and he recounted an incident when he and a couple of his friends were nearly caught with stolen jewellery by cops near Indore and had to run for their lives, in doing which, one friend was shot and died. That was the day, he realised, evidently, that the smuggling business was too risky.

Now, many may say that stories such as these are entirely made up, and certainly I have no evidence to suggest otherwise, but I like to think that, shorn of all embellishments, there is still a core that is true. When I read Ishmael Beah’s fascinating memoir -- A Long Way Gone -- a remarkable, though somewhat inelegantly written, account of his time as a boy soldier during the civil war in Sierra Leone, I found it replete with incidents and stories that are vague and nearly impossible to verify.

To consider a great many of his experiences to be imagined or entirely fabricated, though a perfectly plausible response, is, however, taking the easy way out. Why wouldn’t you rather believe? What, after all, is the point of listening to the stories of strangers, if one has no intention of believing them?

Kindly click NEXT to continue reading

Travel tales: The most amazing stories from UP to Italy

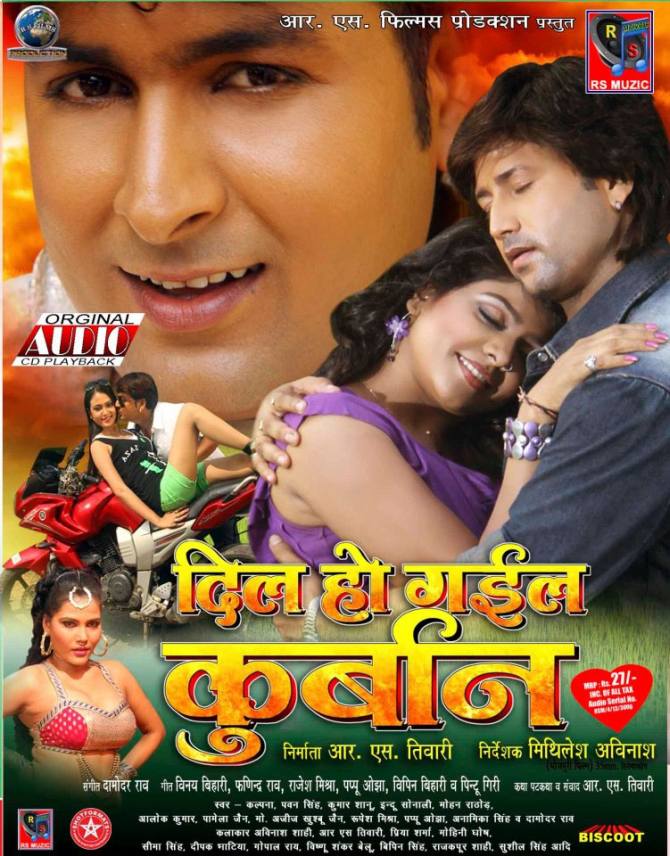

Back on the charpai, our conversation ended before the tea did -- there were second servings of it -- and we sipped it in silence, until the man asked if I am interested in films. I answered in the affirmative and braced myself for the usual queries regarding the latest Hindi films and whether I’d watched them and what I thought of them, but instead, he announced he has made a couple of Bhojpuri films and is working on another and if I wanted to see the posters of his films. His father, without waiting for my response, called out to someone inside the house and asked for the posters to be brought out.

I asked what he meant by ‘made’ films, half expecting him to have invested money in one in return for a mention as a co-producer, but he clarified that he has made them himself. Written and directed by, he emphasised, and when the posters were brought out, I found it was indeed so. The posters are for his third film, he explained, and added that he also has a trailer of the film on his cell-phone, if I’d be interested in watching it.

I, of course, agreed -- I doubt if I had a choice anyway -- and he handed me his phone. The trailer was nearly six minutes long (the glorious freedom of not having to bother about TV spots!) and, to be fair, looked alright, as far as these films go; it was only as good or bad as any other Bhojpuri film trailer I have seen.

I asked him about how much money it takes to make these films and where he gets his equipment from and he answered my questions in great detail, clearly happy to have found an eager audience. I suspect that most people he meets aren’t nearly as enthusiastic about it.

His next film will win the Oscar, he declared after he was done explaining the intricacies of camera work and editing. The Oscar, I asked incredulously, and he nodded solemnly and said it will be the greatest film ever made, for it will be about the religion of Christianity -- a subject that no film has ever tackled before.

I had no intention of contradicting his claim and instead, asked why he should want to make a film about Christianity and he immediately jumped into a long, seemingly well rehearsed, sermon on how great the Christian faith is and -- well to cut a long story short -- how a priest from a church in Kerala had graciously shown him the light and, more importantly, the money.

I don’t think he fathoms the full extent of what he is being asked to create and what it will most likely be used for in the future, but he understood enough to not mention the priest’s name or the name of the church when I asked him for it.

I left wishing him well and cracking the odd joke about him having to wear the company shirt to the podium for his Oscar acceptance speech.

Kindly click NEXT to continue reading

Travel tales: The most amazing stories from UP to Italy

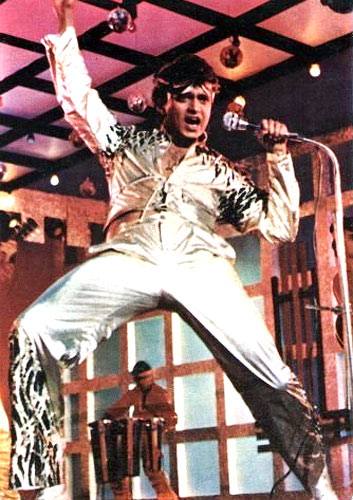

As I write this, I remember other encounters from my time on the road. Several of them, unsurprisingly, are built around the subject of films. By virtue of their accessible and largely uncontroversial nature, films are often the simplest conversation drivers, in unknown lands with unknown people one has just met and perhaps will never meet again. I remember, in Russia, how often we were approached on the streets to be asked if we were from India and when we confirmed it, how often the names of Raj Kapoor and Mithun Chakraborty were mentioned, including one occasion in Ekaterinburg, where the two local boys we’d just met, broke into a jig on the street and sung ‘I am a Disco Dancer’, even continuing as far ‘zindagi mera gaana’.

And the time we were wandering through the streets of Bologna and chanced upon a snack joint called ‘Oye Punjabi’ with large posters of Celina Jaitly inside. The owner of the joint, we found, was from Pakistan and spoke fluent Punjabi and some Hindi and when we asked him about the posters, he confessed he didn’t know who she was but found her exceedingly beautiful.

He offered us free soft drinks, to go with the food we’d ordered, and spoke of how, so far away from our lands, we were the same, him and us.

Kindly click NEXT to continue reading

Travel tales: The most amazing stories from UP to Italy

There is, inevitably, the odd occasion when this leads to an atrocious time, such as the time, a bunch of us -- a dozen boys and girls of various nationalities -- lounged about in semi-darkness in our hostel in Irkutsk, late in the night, and somebody hit upon the ludicrous idea of having everybody mention their favourite actors and actresses and films and so on -- a game which, I believed until then, one grew out of before one grew out of teenage -- and for the next hour I suffered through a list of names comprising the Michael Bays and Twilights of the world.

There was, of course, the saving grace of there being beer bottles in our hands and in the fridge, and I partook generously from it throughout, though in hindsight it was perhaps not such a clever idea, for, the next morning, I seemed to recall the name of Bergman featuring at some point during the night but couldn’t recall who it was that had mentioned him (or her. Either way, a commendable choice) and lost a potential friend forever.

Kindly click NEXT to continue reading

Travel tales: The most amazing stories from UP to Italy

None of these experiences, though, are as entertaining and as absurdly strung together as they were in Ventimiglia, where we -- a close friend and I -- spent a couple of hours in the summer of 2009.

Ventimiglia is a small Italian town on the Riviera, right at the border with France, in the province of Liguria. It is of particular significance as a train station, since it is here that the French lines end and the ones from Italy begin, and crossing over from one country to the other requires a change of trains.

We arrive in Ventimiglia for precisely this reason, on our way from Paris to Genoa. We have a couple of hours to kill before our train to Genoa arrives and decide to spend them exploring whatever little we can of the town.

The journey up to Ventimiglia itself has been eventful, starting with announcement of a workers’ strike in France -- a rather regular occurrence, we were told -- which had led to some mad scrambling around the gigantic Gare Du Nord (one of Paris’s main train stations) for tickets and timetables.

Once that was sorted and we were on a train, we found ourselves in the company of a stunning Italian woman -- in her mid thirties and, ostensibly, her tightest leather jacket & pants -- and an old balding man with a bad limp, also Italian.

The man spoke some English and the woman, next to none, but she tried hard to make conversation and accompanied us out on to the platform for a cigarette wherever the train stopped.

Halfway through the journey, when the lady had dozed off and the conversation had flagged and I had resumed reading On the Road, the old man asked to see what I was reading and when he saw the name, he said “Oh, I wrote that book.”

I stared at him in amazement, not quite sure if he took us for absolute idiots and seriously expected me to believe he was Jack Kerouac.

He seemed to realise there was something amiss and by way of clarification, put his hand up and smiled and said, “Long back. Twenty Years. Not in English. In Italian.”

“In Italian?” I asked.

“Si”

“You mean you read this book, don’t you?”

“Si…yes, read it, yes”, he said, a little embarrassed.

I broke into a smile and so did he, and we left it at that and I will never know if his was an honest mistake or a hopeful shot at a con game.

Kindly click NEXT to continue reading

Travel tales: The most amazing stories from UP to Italy

We walk out of the station and into Ventimiglia at five in the evening. It is summer and there is plenty of sunlight. There are three streets that lead away from the station, one to each side and one straight ahead, and we choose the one leading straight ahead, for we can glimpse the brilliant blue of the Tyrrhenian Sea at the other end. Later, when we’ve walked around some more, we realise that the straight street is like a diameter to the other two streets, which circle briefly around a block or two and meet at another T junction near the sea.

Behind us, on the other side of the station, low hills of dense green rise above the town and stand starkly against the clear blue of the sky.

The street is lined with low, white and rose-tinted buildings. Sunshine breaks into the street from the other end, melting the edges of the farthest buildings in a yellow haze. Most windows are open and the glass-panes turn the white light into a magnificent orange. Nearer us, the town emerges from the halo and transforms into precise shapes in the shadows. Flower pots hang from balconies -- roses and geraniums, well looked after. We walk languorously, stopping often to take a picture or remark upon something we see.

The sea is a deep clean shade of blue, just as the images of it we have seen on the Internet promised. There is a wide beach of white sand between the street and the sea. On the sands, a couple of stray dogs scamper about, a sight we find most remarkable, for until that point, we haven’t seen a single stray animal on the streets throughout our time in France. On our left there is a concrete pier that juts out onto the sea. There are wooden benches on it, most of them unoccupied. On the right, the old part of town -- a dense multi-coloured cluster of buildings -- rises above us. We decide there is too little time to be able to explore the old town and turn instead, towards the pier and its benches.

It is on the pier, that the second of the string of remarkable encounters takes place. We spot two young men on one of the benches and when they see us, they smile widely and walk up to us. One of them starts speaking and it sounds neither French nor Italian, and we shake our heads and shrug and say “English only”.

“Sri Lanka?” one of them asks.

“No. India”

“Morocco”, they offer.

We fall silent, all of us, but nod and smile at each other to show we appreciate the company. They try again.

“India” he says, and starts flailing his arms around and when he realises we look bemused he asks his friend to join in too and the two of them flail their arms together.

“Dance?” We ask.

They shake their heads and resume trying. One of them draws rectangles in the air with his fingers while the other places his hands close to his ears and opens shuts his palms, and says something in a singsong voice, accompanied by an imitation of drumbeats.

All this goes on for a while, until eventually, one of them remembers the word ‘Bollywood’.

“Ah yes, Bollywood.”

“No. Indian Cinema” corrects my friend, who is somewhat touchy on the subject of films.

They are jubilant. “Bollywood! Bollywood” they repeat, and then “Oscar! Oscar!”

“Oscar?”

After a great deal more gesturing and head scratching, most of which is impossible to reproduce on paper, we realise they mean Slumdog Millionaire.

“India slumdog!” they exclaim, after we have guessed the name of the film, “Morocco slumdog!” which is, presumably, a comment on the poverty-stricken nature of the two countries.

“No no,” my friend protests again, and I look at him in amazement while he continues, “Slumdog Millionaire is not an Indian film. It is produced in Hollywood and made by a British Director. Also, we didn’t like the film much…”

The two Moroccans nod gravely through all of this, and then go on to repeat “India slumdog! Morocco slumdog!” again.

I burst out laughing.

Soon, it is time for us to return to the station, and when we start to shake their hands and say goodbye, one of them produces a straw hat out of his bag and hands it over to us and then points to the gold ring my friend is wearing.

“Souvenir”, he says, pointing first to his hat and making a show of handing it over to us and then pointing at the ring again.

“No”, we say, and hand back the hat at which they appear crestfallen. We walk away briskly and check once or twice if we are being followed. We aren’t.

Kindly click NEXT to continue reading

Travel tales: The most amazing stories from UP to Italy

On the way back to the station, we walk by a hotel, and consider spending the night in Ventimiglia. It seems like a nice enough town, the Moroccans notwithstanding. The man at the reception quotes a price that is too high for us and we decide against it. He shrugs when we shake our heads and start to head out and asks where we are from. When he learns we are Indians, he says he has read the Upanishads. We stare at each other -- after the last few hours, we are no longer sure what sounds believable and what does not. We haven’t read the Upanishads ourselves, we tell him politely, and leave.

Back at the station, we find the platform nearly deserted, except for one middle-aged man, who turns out to be a Scot on his way to Rome for the Champions League final (this is 2009 and Manchester United play Barcelona). He does not have tickets to the match but is going anyway. If not inside the stadium, at least he will be in Rome, he says. We discuss the match for a while and when I suggest Barcelona is likely to win, he showers me with expletives.

He gets on the same train (exteriors filled with colourful graffiti, most unlike the clean sophisticated nature of its French counterparts) with us, but finds himself a seat in a different compartment. At some point during the journey, he comes to us, eyes gleaming with maniacal glee, and tells us how he helped the Ticket Checker catch a co-passenger who was traveling without tickets. Before we have time to respond, he turns and dashes back to his seat.

Our day ends near midnight in a comfortable and cheap hotel room in Genoa. A window looks out on to the neon-lit street below, now empty. But it will fill up next morning, we know, with people and their experiences and their stories.

Top stories we would want you to read

Click on MORE to see another feature...