| « Back to article | Print this article |

In the footsteps of the snow leopard

Trekking in Spiti, Himachal Pradesh, Sumit Bhattacharya stumbles upon a conservation success story.

Yeh toh jhatpa ka lagta hai (this seems jhatpa's),” our guide, Keshung said, handing me a tuft of white fur on the trek from Komic, billed as Asia's highest village, to Demul, another 14,000-plus-foot high village in Himachal Pradesh's Spiti valley, adjoining Tibet.

Minutes earlier, Keshung had disappeared into the mountains above, following what he thought were fresh pugmarks of jhatpa – the colloquial Spiti word for the super rare and super elusive snow leopard.

We were above 15,000 feet, though altitudes are fuzzy here, in this trans-Himalayan region that Rudyard Kipling described as 'no place for men' in Kim. For instance, Wikipedia lists Hikkim, the village before Komic, as at 4,572 metres or 15,000 feet, but Hikkim is lower than Komic. And then again there are villages in Ladakh and Tibet that can perhaps challenge the Spiti gang.

All I can tell you is that the Diamox (a medicine that puts the kidneys on overdrive, helping acclimatise faster) helped. Statutory warning: Do not try without doctor's guidance, and beware that you will leak buckets.

We had followed Keshung, and found clear pugmarks on the soft earth beside a mountain stream. Keshung pointed to a ruffled shrub on which the snow leopard had rubbed its body. That's where he had found the tuft.

Trying to fight the gooseflesh, I put the white tuft carefully in the front pocket of my waist-pouch.

In the footsteps of the snow leopard

Snow leopards, found in only 12 countries, all in Asia, are among the holy grail of wildlife sightings. From Kashmir to Arunachal, it is estimated that just about 200 to 600 – yes that's how little is known – of the rare big cats live across the Indian Himalayas. Their penchant for secrecy is so legendary that they are called the grey ghosts of the mountains.

But here we were, staring at hours-old pugmarks in July!

Fifteen minutes later, as we walked on towards high meadows dotted with wild flowers and almost planned-garden designs, we saw a yak abandoned by its herd (the villagers allow yaks to roam free through the summer months, and bring them in for winter). It seemed injured, unable to get up.

“Only a leopard can do that,” said Tsering, the owner of the two and half donkeys with us carrying our big rucksacks. “Can't be the dogs or the wolves – they won't take on a yak.”

Apparently the cuddly dogs you see in Kaza, the administrative headquarter and main town of Spiti, roam in packs through summer, killing and eating whatever they can, including domestic sheep and bharal or wild 'blue sheep', a major food for the snow leopard.

To Keshung, whose house is the last house in Komic, a village of 116 people, and faces a mountain stream, the snow leopard is a nuisance.

“It jumps 9-foot high walls with sheep in its mouth,” Keshung declared. “Especially in winter it will come into the village at night, and all the dogs will start barking, and we will have to go chasing it! But nowadays they are coming less into the villages.”

Why, we had learned in a serendipitous meeting a couple of days ago at Kibber, Spiti, where snow leopard research has been going on since the 1990s, and where the Indian government's Project Snow Leopard is to set up its first centre.

In the footsteps of the snow leopard

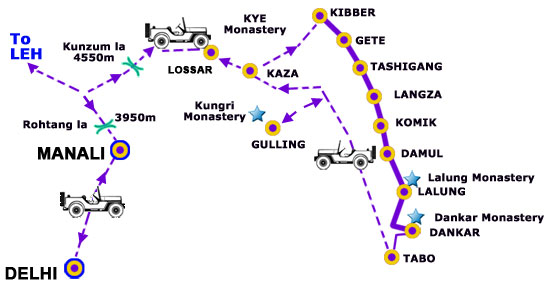

We had gone to Kibber (listed at 4270 metres or 14,200 ft) as an acclimatisation afternoon outing before our trek, that would take us though Langza, Hikkim, Komic, Demul, Lhalung and Dhankar; picturesque high villages on the left bank of the Spiti river, which originates around the Kunzum La (4,590 m or 15,060 feet) that separates Spiti from Lahoul (Lahoul & Spiti make up a district, with administrative seats in Keylong and Kaza respectively) and eventually joins the Sutlej – flowing down from Tibet – in Kinnaur district of Himachal Pradesh.

At Kibber, I had gone into my usual routine of asking everybody if they had ever seen a snow leopard. The amused Chaiwallah – after growing tired of my questions when he told me he had seen one last month – pointed to a figure in a faraway house, watering plants. “He knows the most about snow leopards.”

Soon, Sushil Dorje was with us, transforming our understanding of the valley.

Much later, we were to learn (thanks to the Internet) that he is the recipient of a Dutch award for snow leopard conservation and reducing man-animal conflict. But in that Chaishop, like typical city idiots, we asked him how much money he would take to show us around. He would have none of it, and instead readily came with us in our car higher up above Kibber, in the area that is the Kibber Wildlife Sanctuary.

In the footsteps of the snow leopard

After a brief walk, we were rewarded with our first sight of blue sheep or bharal, the staple diet of the snow leopard. If there are not enough blue sheep and/or ibex, snow leopards have to turn to livestock for food.

We learned, thanks to Dorje, that the bharal population in upper Spiti valley had increased to 700 because of efforts of conservationists like Charudutt Mishra and Sumanta Bagchi, who had through scientific studies shown the connection between dwindling prey base and snow leopards attacking livestock -- goat, sheep, horses and yaks.

Another reason for the increased blue sheep population is the hopefully changing mindset of the Indian Army. When high altitude expedition teams head up, the local organisations try to educate them about the importance of not killing animals like blue sheep for food or sport. “The older officers shoo us away, but the younger ones get it immediately,” Dorje said.

And that is why the snow leopards in Spiti are coming less into conflict with the villagers, at least in the region around the Kibber Wildlife Sanctuary.

The region was also one of the first in the world to start a community insurance project for livestock killed, and coupled with the people's Buddhist belief in nonviolence, retaliatory killings of snow leopards are rare here.

In the footsteps of the snow leopard

There are 35 to 40 snow leopards in the upper Spiti valley, Dorje informed us. He should know, he was involved in the setting up of camera traps across the valley, one of which we would see later, trekking from Kunzum La to Chandratal.

And he clued us into the ways of the Tschen – the more formal Spiti word for the snow leopard.

The cats don't hunt in the meadows like the Tibetan wolves do. Snow leopards walk along ridge lines and cliffs. And they are also creatures of habit.

“There are areas we dub as 'national highways', meaning snow leopards will always pass though those paths,” Dorje said.

We walked along one such ridge line, gasping for air at the incredible sight around us as well as the realisation that we were walking on the footsteps of snow leopards. Dorje showed us scrape marks (snow leopards scrape the earth with their hind legs in a pre-hunting ritual). But we couldn't find any pugmarks – probably because of the wind-swept topography.

The government, he said, has okayed tranquilising and radio-collaring a snow leopard in Spiti for scientific studies, but the means – whether the animal will be shot, or captured and injected, or given food laced with sedatives – is yet to be decided.

Schoolchildren in Spiti also go for summer camps with the Nature Conservation Foundation, an NGO which is a Project Snow Leopard partner, in the mountains above Kibber. The average Spiti schoolgoing child does three such camps – one each in Class 7, 8 and 9 – and is educated about the region's fragile ecological balance.

The international Snow Leopard Trust – which works in five countries that are home to 75 percent of the wild snow leopard population – has chosen upper Spiti valley as its focus area in India.

In the footsteps of the snow leopard

Spiti is a mystical, magical land. Here, someone like Dorje, who rattles off the scientific names of all the plants and animals, will also tell you about how when a group of trekkers went missing, they called the gods – a séance where the holy spirit speaks through a person. The gods said the trekkers were dead, and told them the location. A rescue team went up and Dorje carried a trekker's body down on his back.

For most of the year, the Spiti valley remains cut off from the rest of the world. For about three months, two roads, one from Shimla (cut off by the massive rains that wreaked havoc in Uttarakhand last month) and one through Rohtang and Kunzum passes from Manali, open it up to few tourists – fewer this year – and trekkers.

When we were there, the entire valley had not had electricity for half a month. Apparently, fed up with the erratic power supply, the people of Kaza had written to the district administration that if this is the kind of power supply you are offering, we don't need it!

Solar panels have been a better energy source here in the land of abundant sun.

We had many misadventures in Spiti, including aborting a raging-river crossing attempt, and a disastrous 4-hour, 1,000 metre climb that totally killed us. We saw amazing vistas, found fossils from the Tethys Sea near Langza, and lived in the village homestays with very warm people. Watching the avalanche-hit-and-mummified lama's body in Giu, barely a few kilometres from Tibet, was surreal.

But nothing quite beat the thrill of scanning jagged mountains directly above, looking for the snow leopard that must have been biding its time to finish the yak kill. It's not often that they eat yaks (4 percent of snow leopard diet only, according to a Mishra and Bagchi study).

Tourism here can be a threat, but I am counting on that 'road' from Rohtang to Kunzum – on which our hired Scorpio broke down and a kind trucker rescued as by giving us a ride till Batal – to keep the pesky ones out. That, and the dry compost Spiti village toilets.

Across Spiti, I showed my tuft of 'snow leopard fur' to anyone and everyone I could. One day it was gone. Serves me right for trying to take it away from where it belongs.