| « Back to article | Print this article |

Anatolia: Chasing the absurd and the exotic

Kushal Chowdhury describes the adventures and joys of running into unknowns when one travels without a proper itinerary as he witnessed during this tour through remote Turkish towns on its south coast.

Like most people who like to think of themselves as 'travellers' and not tourists, I too prefer as loosely drawn an itinerary as possible so there can be sufficient room for flexibility.

This approach effectively translates into very little pre-booking of transport and accommodation.

The lack of pre-booking, of course, only adds to the charm of the travelling, since it brings with it the promise of cheap hotels in seedy corners, local public transport that is often not designed to be tourist-friendly, chance run-ins with the townsfolk and other assorted 'authentic' experiences.

Unfortunately though, in my experience, the actual result of all of this is hardly ever as filled with romance and adventure as one imagines, and most often, the cheap hotels in seedy corners aren't very different from cheap hotels in less seedy corners and local public transport is, after all, buses and trains.

How different can that really be?

And so it is that when one does run into something even remotely adventurous, it becomes a prized possession in one's bag of travel lore -- a story to be told a thousand times and never tire of.

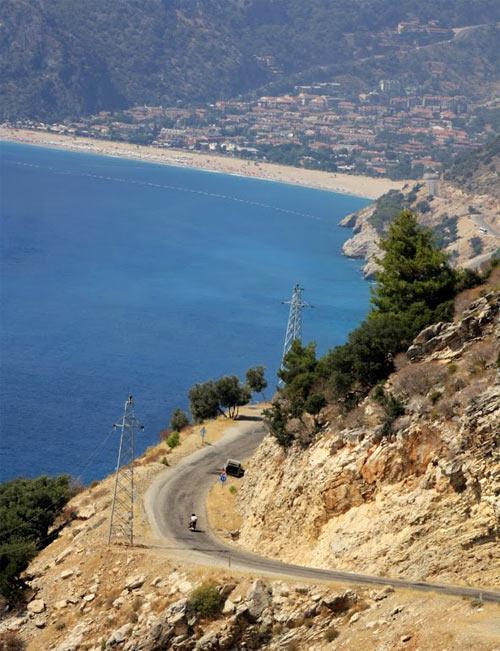

It is a bit like that with one particular leg of our trip through Turkey -- from Fethiye on the southern coast to the town of Birgi somewhere in the middle of Anatolia.

The choice of Birgi as a destination is itself a product of another great cliche in a traveller's repertoire -- to seek out little known places in remote corners, away from the crowds, in a quest to avoid the more commonplace. To be able to smirk when somebody gushes about the view from the Eiffel tower in Paris or the grandeur of the Forbidden City in Beijing or the fabulous beach resorts of Turkey and Greece, and quietly ask "but did you walk the streets of Montmartre after midnight? Did you live in a siheyuan somewhere in a maze of hutongs? Did you go to Birgi, a town full of perfectly preserved Ottoman architecture?"

In Herzog's great documentary set in Antarctica -- Encounters at the End of the World -- he ruminates about how human adventure and exploration lost meaning in its truest sense once man set foot on the South Pole -- the last unconquered place on the planet, and how everything since then is a feeble attempt to recapture some of that original essence.

This fascination with little known places, with chasing, sometimes absurdly, after exotic experiences, is for me, a clear manifestation of the point Herzog makes.

Anatolia: Chasing the absurd and the exotic

Having spent a couple of days in Fethiye -- a standard issue beach-resort town, with the odd Greek ruin thrown in -- we decide it is time to move on.

We still have two spare days available to us before it is time to return to Istanbul, for the flight back to India. We pore over maps and travel books and look for places we can go to until one of us stumbles upon a mention of Birgi on a blog.

It is a UNESCO World Heritage site, we learn, and was a major political center in the past and yet, there isn’t a great deal of detail available on the internet about it, which only adds to our curiosity.

So right after breakfast, we ask the owner of the hotel we are in what the most appropriate method to get to Birgi is.

He is a garrulous middle-aged man, tall and with a handsomely creased face and is perennially dressed in white tee shirts and Bermuda shorts.

He is always available for conversations and has two very pretty daughters whom he tries to keep away from wherever the conversation is.

In general, throughout Turkey, everybody who we have met are wonderful warm people, and seem to have a great affinity for India (they use the name 'Hindustan', India confuses them).

Anatolia: Chasing the absurd and the exotic

The man admits he has never heard of the place.

We show it to him on a map and he explains to us he is still a little unclear on how to get there, but it appears to be close to Odemi? -- a somewhat larger town in the vicinity -- and that there are probably buses from Fethiye to there.

He is, however, bemused by our choice of destination and suggests we go to Selcuk instead.

Selcuk is, by all accounts, another crowded beach resort town and we have no intention of visiting it.

He shakes his head in disappointment and asks us to wait while he makes a few calls and checks if there are buses to Odemi.

Evidently, there aren't any.

We pore over the map again and eventually find that Pamukkale -- another place on the peripheries of our wish-list -- is in the same general direction from Fethiye as Birgi and being a better known tourist destination, we expect it to be better connected.

He again makes a few calls.

We are told the only bus for the day has already departed and that perhaps now we should consider Selcuk again. We politely decline.

Another set of calls later, he comes back to us, beaming.

About 20 km from Pamukkale, there is a town called Denizli, on the highway to Izmir and there are buses that pass through it throughout the day. He offers to arrange for tickets for the next bus and asks us to pack as quickly as we can.

Ten minutes later, a portly man in a car comes along. He will take us to the bus, the owner tells us.

The car ride lasts fifteen minutes, during which the man states he has never heard of Birgi and that Selcuk is a wonderful place.

The car ride ends abruptly, right in the middle of a road, when we spot a bus coming towards us and he mutters something under his breath and swerves the car right on to the path of the bus.

I imagine us in a film, stepping out of the car in slow motion, assorted arsenal in hand, and a little while later, blood spatters on a cobwebbed windshield.

Anatolia: Chasing the absurd and the exotic

The driver of our car and that of the bus have a brief conversation and a few minutes later, the bus continues on its way, with us in it. We are travelling without official tickets and the personal wealth of the two drivers has risen a few Turkish Lira.

The bus is state-run, it appears, and considerably less plush than the privately run service that brought us from Cappadocia to Fethiye. Nevertheless, the glass panes of the windows do not shudder too noisily and the seats are adequately cushioned.

There are a handful of people in the bus -- middle aged and the elderly.

None of them looks like a tourist, and for the first half hour, they cast frequent sidelong glances at us and murmur and giggle amongst themselves.

There is no pretty face in the bus that we can cast sidelong glances toward.

Soon, we leave Fethiye behind and are travelling through the gorgeous Anatolian landscape, vast gently rolling shades of green and brown.

Grey shadows of white clouds glide gently over everything, changing shape with the contours of the land. Denizli is four hours away.

Anatolia: Chasing the absurd and the exotic

With recounting most interesting travel experiences, the great difference between the actual experience and the recounting of it, is time.

A story can be only as long as it needs to be while the experience lasts as long as it takes.

What must sound like eventful, even exhilarating, journeys are often filled with long stretches of sheer inactivity and utter boredom.

And even the good bits, the really interesting bits, are often nothing more than fleeting images and impressions that are impossible to recreate, even recollect.

A lonely tree in an expanse. A particular expression. A stack of stones by the road. A cluster of buildings in the distance. The glare of the sun on a window.

And so, there is regrettably little that I can reproduce on paper from this trip, although it remains one of my most satisfying and memorable ones.

On the way we stop at a village for tea.

The tea is served in similar tiny glasses with thin waists like in Istanbul and Cappadocia.

The village wears a look not dissimilar to an Indian village.

The exteriors of buildings are bright shades of blue and green, and everything else is pale shades of brown and yellow -- the streets, haystacks, dung.

The village centre is a tree with a large shade and the cafes are filled with old men reading newspapers. The women wear colourful scarves and stare from behind half-open doors and windows.

Anatolia: Chasing the absurd and the exotic

It is the same with every village we pass throughout our time in Turkey.

We reach Denizli just after noon.

The bus station is just off the highway and the city itself lies invisible somewhere beyond a low hill.

The bus driver gestures to us to wait and wanders off. He returns with another man, who speaks good English, and this man tells us he will take us to Pamukkale in his cab.

When we ask him about money, he waves dismissively and says “it is all taken care of”. We look at each other with concern but he is insistent and we agree. Pamukkale is a half hour’s drive away.

When we reach Pamukkale, he drives straight to a tour operator’s office. We are invited into it and offered tea.

A little later a man walks out of a cabin and joins us and asks about our plans. We ask him if he knows how to get to Birgi, but he shrugs and says he has never heard of it.

He suggests Selcuk, instead.

We smile and shake our heads.

He shrugs again and offers us his card. "If you have a problem, I am right here", he tells us and disappears back into the cabin. We walk out of the office.

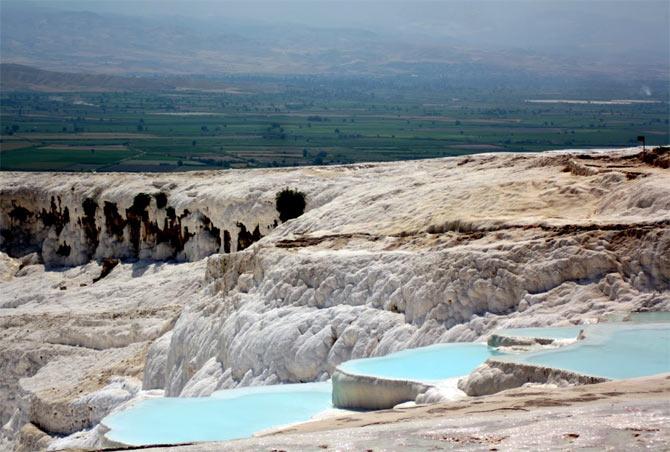

Pamukkale is a very small town and gets its name from 'Pamuk' which means cotton.

It is famous for its stunning hot water springs and travertines -- naturally formed terraces on a hillside made over thousands of years by mineral deposits from the springs.

It is quite a sight, and we have seen pictures on the internet that are astonishing. The problem though, is it is just that. One great sight, stunning and jaw dropping and all that, but just one sight.

The hill, when it comes into view, is completely white, like snow.

The travertines are visible from the bottom but one has to climb up to the top to be able to have the best view of it.

We walk up the crescent shaped hill, shoes in hand, for the ground below is slippery with the white lime deposits and water flows continuously over it.

The travertines are always in sight and always magnificent. Small pools of hot spring water are formed all over the hill and tourists in bathing suits swarm in and around them. We reach the top and take a few pictures and come back down, all in the space of an hour.

There are no buses from Pamukkale to Odemi?, we find.

By now, we have stopped asking about Birgi altogether, for as incredible as it may sound, it is clear that nobody has heard of the place. We are not sure if we will be able to get to Birgi at all, but are determined to give it our best shot.

Even if we don't get there, we will get somewhere, we know. Somewhere that is not called Selcuk. That is all that matters.

Anatolia: Chasing the absurd and the exotic

A man we meet at a restaurant suggests we take a bus to Izmir, one of the more important Turkish cities, and get down at a place called Aydin.

From Aydin, he tells us, we will find something to Odemi. He speaks in Turkish and since we do not understand it, also communicates all this in gestures and by pointing at the map.

I have noticed that because the Turkish language in its cadences, its ebb and flow, is similar to Hindi, it sounds oddly comforting to the ear, although we do not understand any of it.

We too, therefore, at several points during the trip, have chosen to speak in Hindi instead of the English that one usually uses in most foreign countries. Perhaps they too find the sound of our voices comforting.

We follow his advice and board a bus to Aydin. This time we buy tickets and in two, uneventful, hours reach Aydin. The bus drops us off a little before the town, on the highway itself, and a helpful co-passenger points to a smaller highway leading away and says Odemi and Bus.

Anatolia: Chasing the absurd and the exotic

We stand there, in the middle of nowhere, and the sky near the horizon begins to turn orange.

The landscape around remains breathtaking but the clouds in the sky no longer draw patterns on it.

There is nobody in sight.

Vehicles fly by on the highway to Izmir.

The other highway, the one that leads to Odemi, remains empty.

In the distance, there are two chimneys and they blow thin lines of grey smoke.

We walk up and down the smaller highway a few times, though we are not quite sure what that will accomplish.

Our gaze alternates between the horizon and our shoes. We remain silent. A half hour passes.

Finally, a bus appears. It is the most ramshackle we have encountered in Turkey yet. There is rust on the doors and the window frames. It is crammed with people. But most importantly, it is headed for Odemi.

We find seats right at the back, and the driver, who also doubles up as the ticket checker, seeks us out, grumblingly, and gives us our tickets.

We are not sure what the glares and grumbles are for, but a few stops and new passengers later, we realise the convention is to approach him for tickets when one enters the bus.

The bus remains crowded throughout.

Anatolia: Chasing the absurd and the exotic

The route cuts right through the mountains that had so far remained on the margins of our views.

The sky turns pink.

We pass several villages on the way.

The shops are shut and there are lights in the windows.

The mountains loom above us which slowly turn blue and then grow constantly darker.

We see spectral shards of light repeatedly draw closer in the gloom until they transform into automobiles.

Our imagination of the Anatolian landscape derives greatly from Nuri Bilge Ceylan's haunting Once upon a time in Anatolia and here, finally, it all appears almost precisely like it did in that film.

We reach Odemi near twilight. At the bus station, we finally meet people who have heard of Birgi. In fact, now that we are in Odemi, everybody knows of Birgi.

It is only about ten kilometers away, and Matador-like taxis to it are available at regular intervals.

We get into one and are, at last, confident we will get there.

Incidentally, it is the first day of Ramzan. And so, halfway to Birgi, when the sun finally sets, the radio broadcasts the evening prayer.

The taxi stops by the road and the prayers are completed in silence. Afterwards, date palms are distributed to break the fast. The taxi starts again.

Anatolia: Chasing the absurd and the exotic

We reach Birgi twenty minutes later and a young man in his early twenties gets down with us at Birgi.

He speaks English reasonably well and offers to help us find a place to stay.

We walk for a long while through a maze of cobblestoned streets lit by warm yellow lamps before we reach the guest house.

It is in a large compound and is run by a family, which lives there itself. The house is old and lit by lanterns and the furniture and the floor creak.

There are wooden benches and tables in the open and we have tea and, a little later, dinner there.

Like we have noticed on several previous occasions in Turkey, it is always the men that serve.

I wonder if this is an indication of a progressive society where men help with domestic chores or an indication of the opposite -- a society where the women of the house aren't allowed to get too close to strangers.

When we go to bed in the night, everything is absolutely still.

When I move, the bed creaks.

Through the open window, I see the leaves of a tree swaying and creating patterns on a wall beyond.

The trees and bushes rustle constantly and wake me up several times through the night, and I instinctively look towards the open window, half expecting an apparition staring back at me.

We spend most of the next day walking around Birgi.

The town is easily among the prettiest I have seen -- all cobblestones and narrow alleys and red thatched roofs.

Elegant houses with elegant, clearly defined, shadows.

We walk through the many alleys and occasionally stop and stare at the views.

We meet no other tourists, only locals who are faintly surprised to see us.

A cafe is open although we can't find many reasons for it to be, during Ramadan.

Every hour or so, we return to the cafe for tea.

We will perhaps remain their only customers for the day.

One of the main attractions -- the Cakiraga Mansion -- is closed for renovation, we are told, but that doesn't dampen our mood much.

We have made it to Birgi -- a town even the Turkish have forgotten -- and our bag of travel lore is richer.

It isn't our fault that somebody made it to the South Pole all those years ago.