P Rajendran

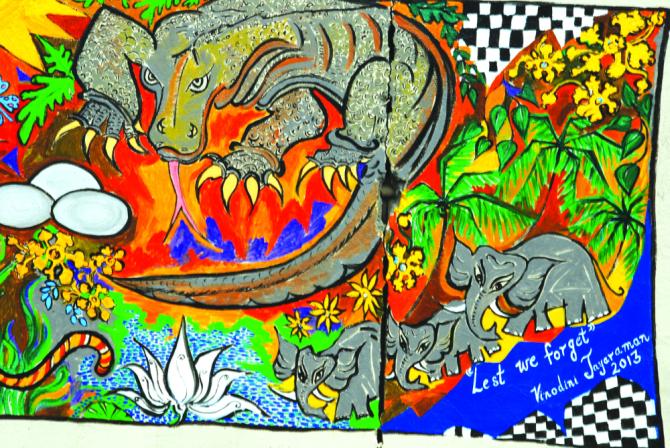

Vinodini Jayaraman began painting as a way to help her get over a frustrating stutter early in life. Now her work, an ode to conservation, covers a 100-foot wall at the University of Memphis.

Jayaraman, a well-known local artist, was called on to paint the mural -- on a concrete wall at the Tiger Initiative for Gardening in Urban Settings -- by Dr Karyl Buddington, director of the campus animal care facilities and associate professor in life sciences.

Jayaraman’s mother Meera Sankaranaryanan had introduced her to painting to help her express herself better. She continued painting through school and college.

She earned her bachelor’s degree in political science from Madras University, and her master’s from the Jawaharlal Nehru University in New Delhi, took the civil service examinations and became an assistant collector in the Indian Revenue Service in 1981.

The work was hectic, and painting fell by the wayside as her training took her to places across India, including the Lal Bahadur Academy of Public Service in Mussoorie in what is now Uttarakhand state, and Kanya Kumari, on the southern tip of India.

“When we travel, we see (all kinds of people and places). I was kind of lucky,” said Jayaraman, who lapses easily and frequently into her native Malayalam.

Still, she was one of three painters selected to display their work at the 1985 Indian Council of Cultural Affairs show in Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala.

She married Karimbumkara Jayaraman, a lawyer based in Memphis, but continued to work in India, taking trips to the United States until 1993, when she quit her job to stay at home and be with her two sons, Sanjeev and Sreedhar.

It was in 1992, she said, that she got back into painting. While telling her son Sanjeev tales from Indian history and mythology, Sanjeev sought a better description of the abduction of Samyukta, the daughter of king Jaichand of Kannauj, by Prithviraj Chauhan, king of Delhi.

Jayaraman sketched the image to Sanjeev’s satisfaction. Thereafter, pictorial depiction became part and parcel of storytelling.

In 1993, Jayaraman held her first exhibition of nine paintings at the now defunct Everest Art Gallery in Memphis. The fact that a painting was sold the first day itself spurred her on to take her work more seriously.

“It was a good omen,” she said, and, as she often does, expressed her fervent gratitude to a higher authority.

Art had always been a means of expression for her.

“My generation of Indians lives in an era of independent India. Photography -- social photography -- was not prevalent. There was only formal photography,” she said, contrasting it with the proliferation of casual photography today.

“Now children take it everywhere. (For us) art was more like a pictorial diary,” she said, describing her own connection with it. “Every time I draw I feel it is for the first time. It is a thrill though I don’t know what it is.”

Yet there was a sense of loss.

“There’s a Marco Polo in all of us. But there’s also a call for the home -- a longing. It’s a pain. One part of you is excited with the wonder of the new world. Yet there’s a longing for the native place -- the house, the pond. You may live in Manhattan, but one part of you will be longing for home. In that loneliness, I started drawing what I could remember from the past.”

Her first trip to Alaska’s Denali forest made her become aware that a lot of what she considered great about India is threatened.

“I realised that wild animals are protected here,” she said. “Then I started thinking that if India doesn’t do anything, we’re really going to lose it big-time. We are trying to conquer space, and we don’t have tigers and elephants,” she said, describing the shrinking range and number of tigers and elephants in India.

There was also a gender imbalance in the Indian elephants because of the demand for the tusks that only the males have.

The problems were not limited to India.

“Last year, 25,000 elephants were killed in Kenya,” she said, adding that she wanted “students to take a second to reflect about endangered animals.”

The richly coloured mural is bursting with fauna: A dozen tigers, nine elephants (her husband’s obsession), besides rhinoceros, deer, peacock, bats, panda, zebra, a Komodo dragon, and even a slightly surprised looking owl.

She had 27 days to cover 100 feet of concrete -- and she worked around holes, grains and pipe fittings. She took in 22 days, five days being lost to the rains.

“Every time I see the wall,” she said, “I don’t know how I completed it.”

Comment

article