| « Back to article | Print this article |

This desi American creates art for social change

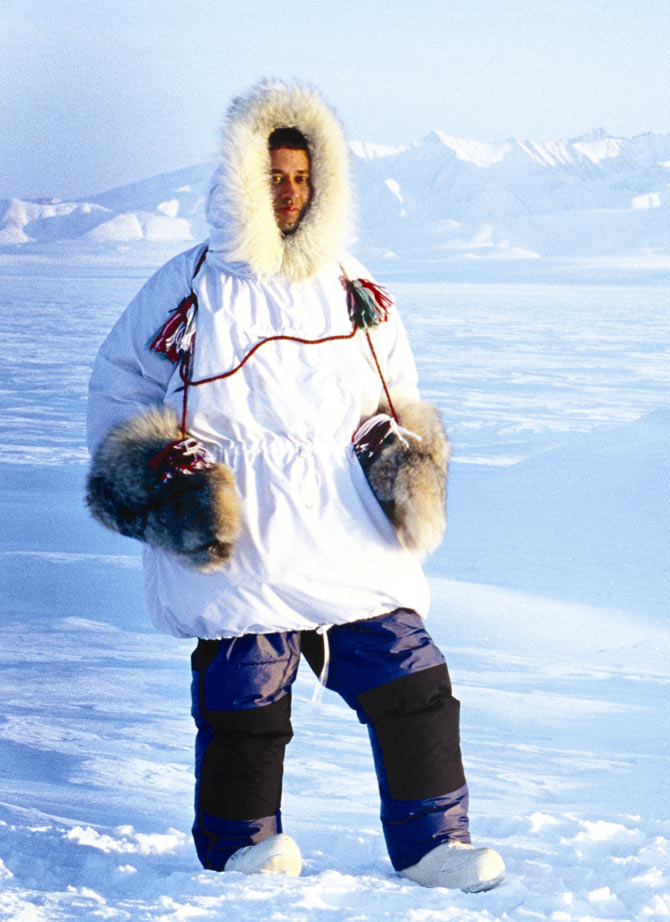

Subhankar Banerjee, whose photographs of the Arctic catapulted him on to the global stage, espouses how his artistic sensibilities help him fight for social change.

Subhankar Banerjee was born in Berhampore (in 1967), a small town in West Bengal, into a middle-class family. Yet art, in its myriad fascinating forms, was never far from him.

It reached out to him in the writings of family friend Mahasweta Devi. It involved him through the paintings of his grand uncle.

And it enthralled him in the cinema of Satyajit Ray, Mrinal Sen and Ritwik Ghatak.

"My grand uncle was a painter, Bimal Mookerjee," Banerjee says. "He was the one who introduced me to art when I was fairly young. I believe my first paintings may have been around when I was 13 years old or so. I used to love art. But having grown up in Bengal, for us, cinema was the bigger influence as a visual art. I used to save my money -- I used to have a little business of selling fish for aquariums -- and go see cinema a lot."

But love it as he did, Banerjee was practical. He had to be.

"My father worked at State Bank of India and we were three siblings (an older sister and an older brother)," he says. "We didn't really have any extra money to think about becoming an artist and making a living (out of it). I did electrical engineering from Jadavpur University in Kolkata, and then came to the US to do a masters in computer science (at the New Mexico State University). I got very bored and moved to a masters in theoretical physics. That's the one I finished first. I came back and finished the masters in computer science in the same year."

Something happened in New Mexico. Banerjee fell in love with its great open spaces.

"New Mexico was a healing place. It was a total contrast having come from India -- open spaces, sparse population."

It was also where his childhood and art caught up with him.

"One of my childhood friends, who also came to the US to study, introduced me to backpacking. I hated that (the idea of the) first trip. Every bit of it. I thought why would anyone carry a heavy bag and go up and down a mountain. After I came back, I was hooked," he says.

"It was at that time that I got involved with the Sierra Club, which is the oldest environmental conservation organisation in the US, as outings chair for southern New Mexico. So, the idea of the outdoors and conservation came into my life simultaneously."

"Also, at that time, I really wanted to get back to art. I even registered for classes in painting and black-and-white photography. I dropped them because physics was too time consuming, but I did make an attempt to get back to art at that time."

What he did end up doing was: "I bought a simple (35mm) camera, and I was taking pictures on these trips. Nothing serious; I was just recording the experience."

It was a hobby that Banerjee kept up with after completing his masters degrees, and through his time at the Advanced Computing Laboratory of the Los Alamos National Laboratory, a job that involved solving problems in energy research.

By the time Banerjee moved to Seattle to work for Boeing -- a research position in the mathematics and computing technology division -- photography had become much more than a hobby.

"It was very serious for me. I joined two photography clubs in Seattle. I bought more serious cameras and lenses; I could afford it now," he says.

His practical middle-class upbringing would keep him at his job at Boeing a bit longer.

"After four years working for Boeing and going on a bunch of trips to take pictures I felt ready," he says. "I wanted to get back to art in a serious way. I was never interested in journalistic photography. I wanted to explore the medium from an art point of view."

Once he began, Banerjee's plunge into the art world was lightening quick.

In a field where artists sometimes struggle their entire lives for a smidgen of recognition, his first photographs catapulted him to international fame.

He is disarmingly matter of fact when he describes what essentially combines 14 arduous months in the Arctic, a book published in the third year of his career as a photographer (Seasons of Life and Land was considered the first comprehensive photographic essay of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge), and exhibitions at coveted museums soon after: "With the Arctic, the first book (Arctic Voices: Resistance at the Tipping Point) came out. Fairly quickly, I entered the art world, where a lot of prominent art museums began to show my work."

He is a lot more forthcoming about what that success meant.

"I realised it was possible to combine art with service to society," he says. "So much of art is done as an individual expression with really no connection to society. (Many) artists hate to connect their work with any kind of purpose. Art doesn't have a purpose -- that is what many artists would claim; that is primarily how artists produce. I have always thought that art has a significant role to play in society, beyond individual expression."

Banerjee decided to combine art and conservation.

"That again goes back to my childhood and the (influence of) people like Mahashweta Devi, who was a noted novelist, but was able to combine her incredible writing with (causes) for social change," he says. "And people like Mrinal Sen, whose films always brought forth social issues. So, if you are an artist, by addressing social issues you are not losing anything. You can still create very serious art. Those two worlds can co-exist. Today, that is what my work has become -- art for social change."