| « Back to article | Print this article |

Ten things you rarely see in India anymore

The telegram, Maruti 800s, safari suits... as India races to embrace globalisation, here are some things we'll miss sorely.

Some years ago. we drew up this list of things that are slowly but surely getting lost in India's race to find its place under the global sun.

Safari suits that were so common a little over 20 years ago are not as popular, the Maruti 800 has been phased out and you wouldn't be able to sate your craving for a Gold Spot even for a million bucks.

Here's our renewed list of things you rarely see in India, if at all.

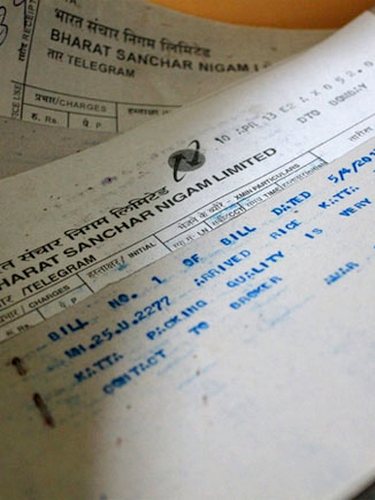

Telegrams

The last telegram in India was sent out on July 14 this year.

With it, the government ended the 163-year-long postal service.

In the face of SMSes, WhatsApp and email, it was only a matter of time before the telegraph service shut down.

Large cable TV antennas

There was a time when large dish antennas atop buildings signalled a certain affluence. It meant you had access to f-i-f-t-e-e-n channels while the rest of us had to make do with one or, if we were lucky, two!

As Direct-to-Home services invaded our lives, the large antenna has made way for a multitude of smaller ones jutting out of all possible corners.

The only reason you'd have one of those satellite dish antennaes on your building today is if you were broadcasting live news or were running a telephone company.

Maruti 800

Back in the eighties and nineties, Maruti used to be synonymous with the Maruti 800.

The car took the country by storm and became the nation's most preferred vehicle, despite stiff competition from the venerable Ambassador and the ubiquitous Premier Padmini.

Launched in 1984, the 800 was seen as the car of the young and the restless, while the Ambassador was preferred by politicians and bureaucrats.

Beginning April 2010, Maruti Suzuki has begun phasing out of the 800 with no plans to upgrade it to Euro IV or BS IV emission norms.

It has halted the sale of the car in over a dozen major cities where vehicles have to be Euro IV compliant.

Sidecars

If you really think about it, the side car was one of the heroes in Sholay.

After all, how many of you can think about the film without thinking about a carefree Jai and Veeru on the bike, singing paeans to their friendship?

For the longest time, sidecars were the closest you could get to a four-wheeler. With this addition, the humble scooter would magically convert itself into a comfortable vehicle for the entire family!

Now, as motor cars are becoming more affordable and young families have larger disposable incomes, the humble sidecar has been pushed into oblivion.

However, Cozy India, the company that pioneered sidecars in India, continues to remain in business, catering to differently-abled people and a few connoisseurs.

Horse cart

Another iconic image from Bollywood -- the tonga or the two wheeler horse cart -- is slowly but surely fading away into oblivion.

Its filmi connections range from the exciting race sequence in Naya Daur (for those of you who are old enough to remember) to Basanti and her famous tonga in Sholay.

The slightly more elaborate cousin of the humble tonga even has a film named after it, Victoria No 203. Interestingly, in all its Bollywood representations, the horse-driven cart is seen as symbolic of everything that is old and noble. In the race to beat time however, there seems no place for either.

Gold Spot

After Coca Cola and Pepsico left the Indian market in the late seventies, the Parle troika -- Gold Spot, Thums Up and Limca -- became the leading carbonated soft drinks.

After the markets opened up and the two companies returned to India, Parle sold the three brands -- and Citra and Maaza -- to Coca-Cola in 1993.

While Coca Cola realised the potential of Thums Up after years of owning the brand -- it has about 13 per cent market share -- Gold Spot was slaughtered in the interest of Fanta.

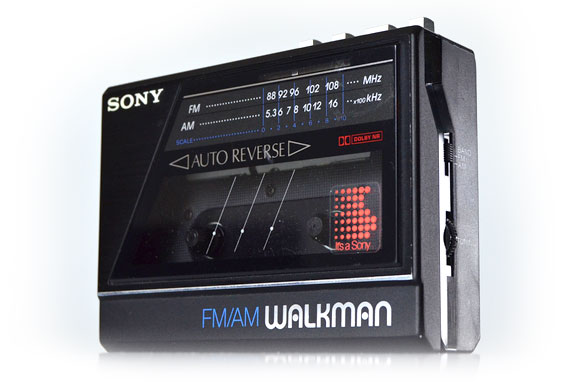

The Walkman

By some accounts, it may be too early to write off the humble cassette which is alive and thriving in smaller Indian towns and villages.

However the portable cassette player, better known as the Walkman, is rarely seen today.

The Walkman was introduced in Japan on July 1, 1979, and made its entry into the American and British markets a year later.

It took the music industry by storm and dominated the music scene for the next quarter century.

Till the early- and mid-nineties, the Walkman was the must-have gadget for the young Indian teen, until it was replaced by the discman (that would skip tracks if you shook it even a little).

The discman had to soon yield to the MP3 players -- particularly the iconic iPod -- which are expected to dominate the music industry for many years to come.

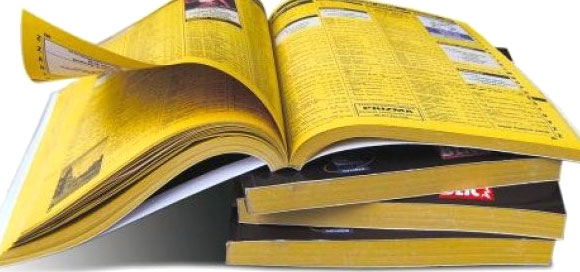

The telephone directory

As we briskly moved from fixed line phones to pagers to mobile phones -- and we do really miss the rotor dial a lot -- the one thing that has slipped away is the good old telephone directory.

Every few years, the wonderous monster of a book series would be delivered to your house by the phone company courier. It would be carefully put away. Every few months, it would to be dusted off to find a number which, more often than not, would be there among the million others.

Readers of a certain vintage will agree that the most thrilling part about the directory probably was the random numbers you could call… just to hear a stranger's voice on the other line.

Safari suits

For the longest time, the safari suit -- a legacy from the British -- was the standard of business dressing.

It went out of fashion in several Western countries by the mid-1980s but continued to prosper in India till as late as the mid- to late-1990s.

The rise of the safari suit can be credited to Reliance Industries, which set up rayon and polyester factories in India. These synthetic fibres, which were commonly used in the making of the safari, were otherwise expensive to import.

The popularity of the safari suit began to wane as the economy opened up and Western companies began to introduce their sensibilities to the Indian corporate world.

Even as the safari suit is often seen as a uniform of the Indian bureaucracy, the younger civil servants are doing away with it, opting for blazers and smart formals. The only reason you'd probably wear a safari suit today would be if you were a security guard or a businessman in a small town.

Pagers

Unlike the telegraph, paging services in India died with little more than a beep. Pagers that became popular in India in the '90s were a must-have for doctors and high-ranking professionals and were at one point considered status symbols. By the time the services were breathing their last, pagers in India were almost exclusively used by couriers and drivers. Like most other things, pagers were killed by the sudden growth in mobile phone sales and before anyone knew it, pagers disappeared from the radar in the mid-2000s, almost as quickly as they had appeared about a decade earlier.