| « Back to article | Print this article |

Magical childhood memories of a day at Juhu Beach

Roasting bhutta, ice golas, lovers, the haunting riffs of a flute -- American-born Sushrut Jangi is bewitched by the intense sights, sounds and smells of Juhu Beach in Mumbai.

I've been to Juhu Beach before when I was a child. I remember that somewhere along the strip of sand my sister, who must have been four years old, came upon a strange and translucent circle on the ground.

"Don't touch it," my mother cautioned.

"What is it?" we asked.

They might be jellyfish, my uncle said. He went to pick one up.

"Don't pick it up!" my sister had screamed.

When we walked a little further, we found that there were dead jellyfish everywhere, gathered in clumps, drying in the sun. They reflected the light back at us as though their glassy bodies were lamps burning on the sand.

I remember later that morning, years ago, I went for a horse ride on the beach. There was a guide on the horse too, who sat in the saddle in front of me. He held the reins and when he shook them, the horse leaped forward. My family watched from the side. I thought we went really fast, maybe a hundred miles an hour. The ocean seemed to be everywhere and I felt as though the horse had lost control.

"Stop the horse!" I cried out, and the man on the saddle seemed as though he hadn't heard me at all.

"Stop the horse!" I said again, and he yanked sharply on the reigns. I got off and remember being upset. Everywhere around my feet there were dead jellyfish. The brilliant things that stay in your memory, na?

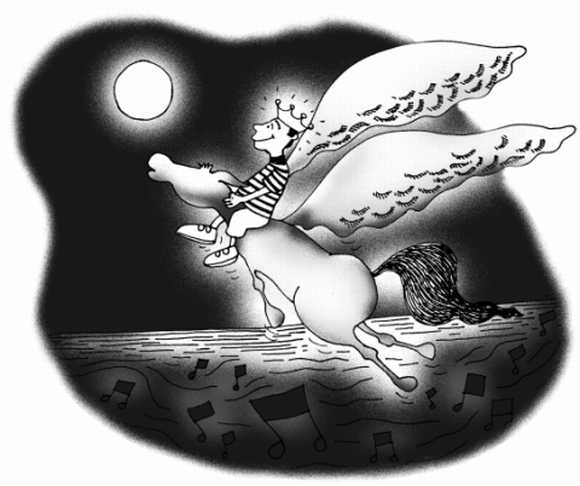

Illustration: Uttam Ghosh

Sushrut Jangi, MD at the Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, was born and raised in America, but says he has a fierce emotional and familial connection to Indian culture.

It's Sunday night, and there's a rumour that Amitabh Bachchan has been sighted

I've been here before, I tell Akshata the evening we go to Juhu Beach, although I don't tell her the story about the horse or the jellyfish. Is there any way I can ever recreate the memory for her in the way that I lived it? It doesn't seem real, anyhow, when we reach the beach.

The place is crowded, unlike the vast, empty stretch that I remember from my childhood. It's Sunday night, and there's a rumour that Amitabh Bachchan has been sighted on the veranda near his Juhu flat. And God it's hot!

We sip on some watered-down Sprite and swallow a chicken tikka sandwich we've purchased from an Indian branch of Subway.

"I can't believe this," I say, when we step out onto the sand. There are people everywhere. I mean, you've never seen anything like this before. It's as though they've gathered for a concert, but there's no show -- only the ocean and the sky and the occasional star breaking through the globe of gray and dusky light suspended above Mumbai.

Isn't tasting the city worth a few runs to the restroom?

Ahead of us is a coloured wheel that's filled with children. It's like a ferris wheel but much smaller, standing about ten feet above the ground. A man stands behind the wheel and stops it every few minutes to let a child stumble off the seat to let another one alight. The children scream because they are dizzy, and after they return to the ground, they run in crooked paths with happiness. Beside them is another wheel spinning in the perpendicular direction.

"Want to get on?" Akshata asks me.

No thanks, I think, feeling a little sick. A tiny child wanders up to Akshata and bumps into her legs and she gasps. The child has no arms; at both shoulders there is only a small appendage, like a finger that the child has some control over.

"It's thalidomide poisoning," she says, naming the medicine given as an antidote to leprosy. Nauseated, I stare out at the ocean. I can almost see the horizon and the curve of the earth, and for a moment, I feel the ground rush forward with the momentum of a merry-go-round.

We walk past the wheels and see that there are hawkers selling food everywhere . There's a vendor selling gola and I feel my mouth water. I've been cautioned against eating gola. "Even I don't eat it," my uncle says. The golawallah makes gola by shaping crushed ice into a ball around a wooden stick. The iceball is put into a plastic cup and then doused with a choice of syrups.

"Which one do you want?" the golawallah will ask, displaying glass goblets filled with impossibly bright reds and blues, as though he's extracted the colours from the skins of imaginary fruit. If you ask a Mumbaiite, the best choice is kala kattha, prepared from black salt and sprinkled with lime, sugar, and pepper. For foreigners, the problem of course, is the ice. It is prepared from brackish water that might have pooled for days on the back of a rusty truck. But that's why gola tastes so good, the Mumbaiites say. It's not the kala kattha syrup, or the limes. It's the taste of the city.

In frustration, I have tried the hygienic gola, the sort made from mineral water at the mall in Lower Parel. The ice is machine crushed and less porous; the syrups fails to fill the iceball the way it fills the handmade gola. It's when I see the golawallah on the beach, sitting with his goblets of syrup and buckets of white ice that I think: isn't tasting the city worth a few runs to the restroom?

The music envelopes the beach, floating out into the water

No, Akshata says, pulling me past the golawallah. Besides him is a woman making bhutta, which is corn grilled on open coals. The fire sends out little sparks onto the dark beach; children play near them as though they are catching fireflies. My mother makes bhutta at home on the kitchen stove. I've never liked it much, but when I see it on the beach, I realise why she makes it.

There's also pav bhaji melting on a tava, and the peas and potatoes hiss as they are flattened into the spicy red mush. The smoke from the onions stings my eyes. Elsewhere there are stalls of pani puri. It's a food that I've loved as a child.

We have sat on our back porch in Boston, in a New England summer that only recalls the summers in Mumbai, and have taken turns scooping the spicy water into the puris, filling them to the brim so that they explode in our mouths. "Do not eat pani puri from the street vendors," I've also been cautioned, but their potential toxicity only adds to their allure. I look up at the rows and rows of stalls and try to take a picture, but in the photograph, they turn into a stream of unending light.

Somewhere, someone is playing a beautiful flute. We push through the crowds to find the source. It smells like sweat, which is the smell of a thousand people. Eventually, we find him playing a wooden bansuri (flute). No one seems to be listening to him directly. There are no crowds that have formed around him. Instead, the music envelopes the beach, floating out into the water, enriched and pushed back by the sea. The melody sounds ancient and real. Strapped to his back is a net of flutes of varying lengths and diameters.

They roll against each other and sound like the branches of trees shaking in the wind.

"Flute chahiye, kya?" he offers me, pulling out several flutes at once.

"No," I shake my head, and he puts them back into the net, bringing the flute to his lips again, moving off closer to the ocean.

We come upon a group of Muslims playing a game. They have formed a ring around two women, who are standing in the middle of the circle. The men are wearing white prayer hats and the women are wearing burkhas, despite the heat of the beach. The two women spin around each other, trying to nab a stone in the middle of the circle. The men clap and watch. The women laugh and scream at each other, and in their excitement, I wonder if their headdress is going to fly off in the wind.

"Don't stare!" Akshata says, and pulls me along.

The moon has come out and looks strangely impotent. Rather than being white, it's a dull copper colour, as though exhausted by the sight of the beach. The waves, though, have picked up, and they reach to the sky. There are a few people standing by the water, running into it when the tide recedes and pulling back when the waves return. Akshata and I stand near the water and she tells me not to go in.

I've often wondered where all the lovers in Mumbai go

Do you know how dirty this water is?" she says. When the wave comes, though, we let it wash up onto our feet. It's quieter here, away from the stalls, and cooler. There are small eddies of wind created by the breaking waves and the breeze spatters our skin with salt.

"I'm standing in the Arabian Sea," I realise, taking a step forward. Ahead of me there are couples walking in deeper water. Some of the women are wearing saris; they walk hand-in-hand with their boyfriends or husbands.

It's a rare thing to see couples displaying their affection in a city filled with a thousand eyes in every corner. Back at home, there is no end to the number of couples kissing in the trains, in the parks, in the shopping malls. Here, the expression of love is bound to the same laws of scarce economy as is water, electricity, and space on the bus. Whatever romance is to be harvested from a congested city is collected with immediacy and surprise; holding hands briefly on a train before the crowd pushes you forward, a shared cold drink under the tents of a market, a walk in a sudden monsoon squall.

I've often wondered where all the lovers in Mumbai go. They are here, tonight, walking along the sand, huddled in the dark rocks scattered along the coastline. Some of them are entangled in passion, others are simply staring out into the blackness of the ocean. Even here, there are single men looking out at the couples with longing; even here, there are wandering eyes. But I like to imagine that there is no desperation in the hearts of these couples; there is nothing indiscreet or shameful about their behaviour. Instead, I hope that the reason they come here is that for the moment, there is the illusion that the crowd is left behind, that even in this city there are small spaces for making the idea of romance possible. It is as though that for an evening, the sea and the city exist only for the sake of their own story.

I'm okay with this thunder of music and people

When we are leaving the beach, the crowd doesn't show any signs of departure. They could go on living far into the night. The moon shines like a white tablet now and the high tide swells. I look down at the sand, to try to find the jellyfish from my childhood, but there aren't any around. It's as though we are in a different place altogether.

"You should come back in the early morning," Akshata says, "when it's more peaceful."

But I'm okay with this thunder of music and people. I can't imagine silence now and I'm not sure I want to. There's enough of that back in the United States.

How would it be, I think, if I were here with my family again? If I were small, and my sister were studying the bodies of dying jellyfish? Could I get on that horse from my childhood, again, now? What if I could ride through this crowd, as though I were a king, seeing the wheels spinning, all the bhaji frying on the tavas, and the lovers walking into the sea?

How would it feel to fly across the sand as though the horse had grown wings? "Should we slow down?" the horse driver might turn around and ask. "No!" I would reply this time, looking at the miles and miles of Juhu opening up in front of me. "Can't you make this horse run any faster?"