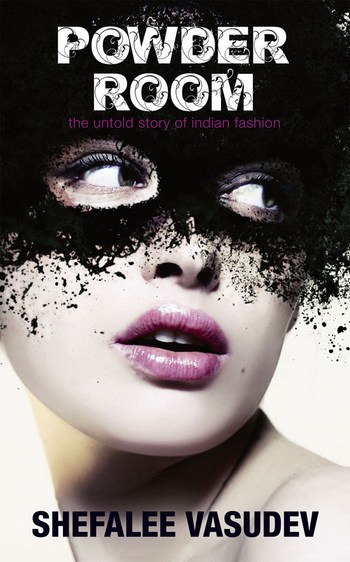

Shefalee Vasudev, author of Powder Room on what it takes to write a serious book on the Indian fashion industry.

It probably has something to do with Madhur Bhandarkar or India's famed 'Page 3 culture' that often equates fashion and showbiz as being frivolous activities that only the rich and airheads indulge in. Justifiably so, the very idea of a serious work of non-fiction about the fashion industry in India evokes some amount of curiosity.

In Powder Room, Shefalee Vasudev the former editor of Marie Claire in India attempts to portray the workings of the industry, without once being gossipy.

The book, published by Random House India, is a serious journalistic piece of work that narrates the story of Indian fashion as it thrives not just on exclusive runways but also in small by lanes of large and small towns, affecting lives in ways we can never imagine.

Even though Vasudev's book lacks historical context, in it that we are thrown in the thick of things quite so suddenly, it is, as she insists, about 'the impulses thrown up by the idea of fashion in India'.

Powder Room however effectively tells fascinating human stories -- from sales persons working in luxury stores to wives of rich north Indian businessmen -- that offer insight into India's ever-changing social fabric.

In an interview to Rediff.com's Abhishek Mande, Shefalee Vasudev talks about the challenges of writing a book on fashion.

How did the book come about?

It was commissioned by Random House when Chiki Sarkar headed it. She would often listen to my observations (and frustrations) about fashion's cliched portrayals in the media compared to its many polarities and inside working and felt there was a book there.

Why did you feel the need to write this book?

To be able to report on fashion with journalistic enquiry and research instead of the maze of parties, trends and products it seems to appear as. I was curious about the stories of people (as opposed to products) whose lives had been changed by fashion and clothing, about their complexities and triumphs.

Could you please talk about the kind of research went into the writing of this book?

I started by interviewing people, whoever would agree to meet me and give me time, show me around their factory, studio, store, even home. I spent many months in trying to unearth what was going on in people's minds about the fashion industry. My questions and interview processes were not very structured but I knew I was moving towards recording behaviours, retail and spending habits, wishlists, familial considerations, generation gap issues, modesty, sexuality, or stories of class and gender that collided with fashion consciousness.

There was something exceptional in Imcha's world view

Image: Shefalee VasudevPhotographs: Courtesy/Random House Publications

What places did the book take you and which one was the most interesting?

I visited many towns and cities in the course of researching Powder Room. The most memorable trips were to Patan in Gujarat to meet Rahul Salvi, the youngest weaver of the Salvi family of weavers who create the Patan Patola sari. The other was a trip to Nagaland to Dimapur and Kohima to meet Imcha Imchen during the annual Hornbill Festival.

If I remember correctly, the first people I met for the book was designer Rahul Reddy and his wife Shruti at their studio in Mehrauli. They gave me a lot of time and patience. Later, as the narrative opened out to new and unexpected alleys, I couldn't use Rahul and Shruti's inputs but will always be indebted to them for their unconditional help.

Could you perhaps share an experience that you came across during the writing of this book and stands out in your memory?

I was most moved by my interaction with Imcha Imchen, the emerging designer from Nagaland (in the chapter titled Boy, Interrupted). There was something exceptional in Imcha's world view, the way he sang beautifully yet nursed a disconnect with the way fashion was being popularly interpreted in India. Meeting Imcha and his family was an eye opener in various ways for me, also the social life of Nagaland that I briefly observed, the Miss North East beauty pageant, these experiences have stood out in my memory.

In many ways there hasn't been a book of this kind written on Indian fashion. What were your reference points? What sort of books were you reading while you were writing this one, not necessarily for subject material but also in terms of style?

I read Emma Tarlo's Clothing Matters: Dress and Identity in India and Lisa Trivedi's Clothing Gandhi's Nation amongst other American and British books on fashion. But frankly, I wasn't looking for a model to emulate. I wanted to explore a refreshing, untried, non-fiction narrative that had fashion as its protagonist but was really a book about contemporary India. I didn't want reference points to guide me because I didn't want my views to be coloured by a particular kind of story telling. As for style, I have always loved The New Yorker, Granta, the magazine of new writing and other compilations where longform journalism is pursued.

'Everyone thought I'd was writing a tell-all, salacious book on fashion'

Image: Designer Rajesh Pratap Singh laughed at the idea of a non-fiction book on fashionPhotographs: Courtesy/Rajeshpratapsingh.com

As an aside, what books do you read? Who are your favourite authors?

I read all the time and respond addictively to books on psychology, psychiatry and popular medicine -- strange as you may find it! My favourite fiction authors otherwise are Jadie Smith, Doris Lessing. This year, I was greatly moved by Katherine Boo's non-fiction -- Behind the Beautiful Forevers. And as I said above, I constantly keep reading issues of the New Yorker, Granta and other journalistic compilations.

What were the challenges you faced as you wrote this book? How did you address the biggest change that all journalists turning authors must address -- from writing regular 2000-word copies to writing a 50,000-word book?

Discipline and repeated attempts at structuring. Keep your head down and write. Select, reject, rewrite.

What were people's reactions when you told them you were writing a book on fashion? What was the one reaction the really stood out?

Most people in the fashion industry thought I was doing a tell-all, salacious book which surprised me as I have never even written a gossip column to give such an impression.

Well, it seemed people thought I was working on a negative, contentious book on fashion, which was never my goal. The most hilarious reaction was that of designer Rajesh Pratap. "A non-fiction book on fashion?" he asked me laughingly loudly on the phone when I first approached him!

Later Rajesh became, or so I would like to believe, a convert to my cause: he understood that I was not out to criticise the industry but to chronicle what was going on.

How did you decide on the scope of the book?

The stories ran away with themselves as I researched. Of course, I did want to focus on a few aspects through fashion -- mental health and societal issues, marital discord, B-grade models, the point and counter point between middle and upper classes, stories of struggling and emerging designers, the limitations and compulsions of the fashion media, something about weavers and craftspersons etc. The stories in the book are representative of the warp and weft of the bigger picture.

From what I have read of you (and you've written of yourself) I suspect you see yourself as an insider-outsider to the world of fashion. How did this unique stand point help you in painting a picture of this world that everyone seems to be fascinated with?

I like to say I am a chronicler not a groupie in the fashion industry.

'Stereotypes and the cliches colour the perception of fashion'

Image: Movie poster of Fashion, pretty much the only mainstream Bollywood film on the industryThe view of ordinary people about the fashion industry is largely restricted to Madhur Bhandarkar's film on the subject. How much of that perception did you come across while reporting for this book? Where was that perception the strongest?

Yes, the stereotypes of fashion and the cliches colour the perception of fashion. It is largely seen as a flippant, indulgent industry where everyone is celebrating and partying or is grasping and glamourous. Few people seem to be curious about the conflicts, the challenges, the hard work, the extraordinary talent that throbs inside the industry. The stereotypes exist of course, but that's hardly the full story.

How much of that perception (as portrayed by Bhandarkar) do you believe is faithful to the industry you inhabit? Do you feel it has perhaps had an adverse effect on fashion as a profession?

It is gradually changing and will change. As the media becomes more curious about reporting on the work of designers and the industry, the cakey view of fashion as a superficial profession is bound to change.

You speak of fashion weeks in your book. How much would you say have they helped the business and the industry (the two major ones of course and the countless smaller ones that have mushroomed across the country)?

Tremendously. They have brought fashion to the forefront as business and got it the national and interntional attention it deserves.

You also portray sensitively the social changes that luxury fashion houses have brought about in these last few years. Could you perhaps talk a bit about the dichotomy of the two Indias and the role of fashion?

I don't think luxury fashion houses have brought social changes. Luxury houses have brought luxury products and thus new ways of conspicuous consumption to the country. Their fall out is a new social ambition in spending or creating social capital through purchase of goods.

The wealthy who are juxtaposed against those who can't afford fine luxury yet want to be a part of that world brings a new set of inequalities. I find these dichotomies very interesting, from a sociological perspective.

On the other hand, global brands have also brought us aesthetic experience and taste. That too is 'change'. So change is not just a storm of new distinctions between classes, it is also how taste is changing in our country. Who buys what in which class is such an enormously revealing commentary of our times.

Stay with the story as long as it takes

Image: Imcha Imchen, whose story is closest to Shefalee Vasudev's heartPhotographs: Courtesy/Imchaimchen.in

Among the many human stories you write about, which was the one story that is closest to your heart? And which one wasthe most difficult to bring out and write?

Imcha Imchen's Boy, Interrupted is the closest to my heart. The one most difficult to write was of Jennifer who works with a luxury brand store and finds her personal life changing with her training and work experience.

You also write about the almost parallel fashion industry that thrives on knock-offs. For the benefit of our readers, could you perhaps talk a little about it? How and when did you come across it first? What do you make of it and the people who are its part?

I haven't written intensely on knock-offs but only mentioned them to give a context. Plagiarism, copying and imitation are rampant in our country but the fashion industry needs a code of professional standards, and clear guidelines and processes to nail it down.

Designers need to take this very seriously and like Ritu Kumar and Tarun Tahiliani leave no stone unturned till they bring the culprits to book. Sitting back and discussing the disillusionments of plagiarism is not going to be enough.

At the end of the book, you speak of young designers who do not want to be seen at fashion weeks and those who will make fashion weeks redundant in the years to come. Could you perhaps explain how you see that happening?

Indie fashion is on its way up. There are designers who do not want to do mainstream work which means they do not want to only make what retailers want, what the media wants to see, what the sponsors dictate or what has to be paraded in a populist way on fashion week ramps with Bollywood stars as showstoppers.

There are new stores and young designers doing delightful work without ever showing at a fashion week or worrying that a magazine cover with a star wearing their clothes is the only way out.

This tribe is independent and it has a voice. Fashion in India needs a voice. So fashion weeks may continue but they will not be the only determinants of success or creativity because Indie designers will not need these platforms.

Even as you wonderfully portray the business of fashion as it is practiced today, I couldn't help feeling that it lacked a historical perspective. Was that a conscious choice?

Yes and thank god you asked this.

This is not a history of Indian fashion, nor is there a chronological order in which I have listed and elaborated on the work of designers down the years.

I haven't talked about the design evolution of Ritu Kumar, JJ Valaya, Suneet Varma, Abu Jani-Sandeep Khosla who are pillars of this industry. Nor is there a chapter on Rohit Khosla.

It is not a book on the "fashion industry" as much as about the impulses thrown up by the idea of fashion in India -- what do we make of fashioin?

What does it mean in the lives of different people? It is a contemporary book, that tumbles upside down the hierarchies -- I have brought in struggling designers alongside the top notch ones, weavers, tailors, salespersons, failed models and such.

Writing it from a historical perspective would have made this book something else which was not the motive.

What were the five greatest learnings you had while writing the book?

- Stay with the story as long as it takes. Keep going back as many times till it reveals itself in its full form.

- Never make the subject of a story a matter of commonplace discussion, idle gossip or casual chatter. Respect people's complexities and confessions and leave them inside the notes.

- Objectivity is a matter of process not just an ethical work rule. Objectivity has to be worked upon by checking, double checking, weeding out personal opinions till the story demands it.

- Never assume. Be ready to change a former opinion if you stand corrected.

- Writing discipline is a great nurturer of good work. Cultivate it like a learned skill.

You can read an excerpt from Powder Room: The Untold Story of Indian Fashion, here and RealTime news updates about author Shefalee Vasudev here!

Comment

article