| « Back to article | Print this article |

Focusing on the POSITIVES of Dharavi: Rashmi Bansal

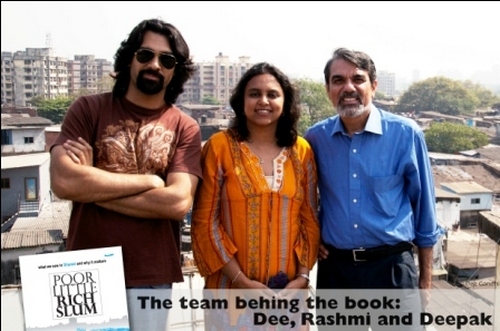

In an interview with Rediff.com, bestselling author Rashmi Bansal talks about her new book, Poor Little Rich Slum (co-authored by Deepak Gandhi) and just why Dharavi is such an important part of Mumbai.

You've probably heard of Dharavi; it's impossible not to have. If you're living in Mumbai, you probably pass by it every day, holding your breath, turning up your nose and trying hard to ignore the filth around you.

The government has, from time to time, announced plans to redevelop the 175 hectares of goldmine into a commercial-cum-residential haven smack in the heart of the city.

Much has changed since the first plans were announced. For starters, the Lehman Brothers (one of the bidders who wanted to redevelop the slum) fell on their faces and led the world into a recession. India stood strong during the crunch; the UPA government got elected twice, following which at least a dozen scams were unearthed, the Greek economy failed and is yet to find its feet and of course, Slumdog Millionaire became a runaway hit, putting Dharavi on the map for the rest of the world.

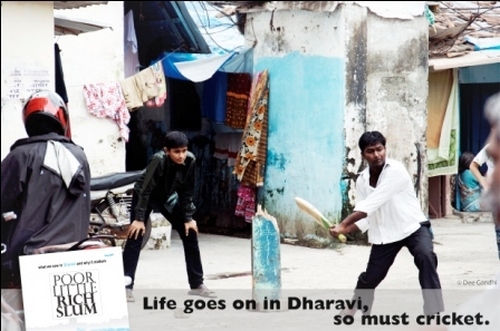

In the midst of all this, though, Dharavi continued to stand and its economy kept itself running.

Over a period of nine months last year, bestselling writer Rashmi Bansal, along with co-author Deepak Gandhi and photographer Dee Gandhi visited the slum, with the idea of writing a book that has now become an institution of sorts.

The result is a crisp little work with a bright blue and white cover called Poor Little Rich Slum: What We Saw In Dharavi and Why It Matters.

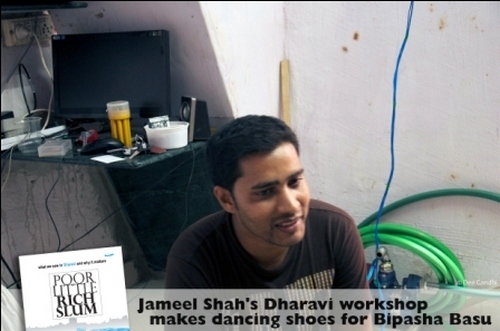

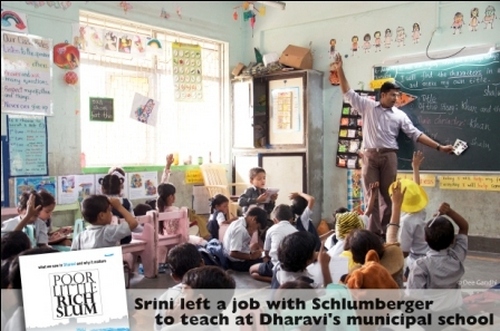

Featured in the book are heartening 'success' stories of individuals who have lived and worked out of Dharavi for a good part of their lives -- a garment maker who started out with almost nothing, a shoemaker to prominent Bollywood stars who ran away from his home with no money, and a highflying executive who gave up his job to make a difference to the children of the slums. These are but three of the many stories featured in Poor Little Rich Slum -- stories that usually get tucked away in the feature pages of newspapers but are now documented.

In the following pages, author Rashmi Bansal talks about what makes Dharavi different and just what she learnt from her visits there. Read on!

'Dharavi has created its own economy'

Tell us about how the idea for Poor Little Rich Slum came about.

It is my fourth book and (like the previous four) it also focuses on the spirit of enterprise and entrepreneurship, but in a very different setting from the previous books.

The idea (of writing about entrepreneurs in Dharavi) came from my co-author Deepak Gandhi, who worked for the United Nations Development Programme and felt strongly about it.

He's visited slums across the world and felt that the slum problem is universal, but that Dharavi is unique in its response (to the other problems that exist in slums). Elsewhere, people use (slums) merely as low-income housing. Dharavi, on the other hand, has created its own economy, one that is not seen anywhere in the world.

So we decided to explore that aspect and find out more about it -- see if we could focus on the positives of Dharavi, rather than the problems that exist there and ones that are extensively written about.

We thought it would be great to explore the lives of people who can rise above (such hellish situations), create something and have dignity and purpose in life.

'There is pride in what people in Dharavi do'

I am curious to know what you mean by dignity, because the way I see it, there really is no dignity in the way people live there. Please could you explain?

For all the times that we visited Dharavi, not once did we have kids tugging at us asking for money. These days there are a lot of foreigners who visit too. They get no extra attention. Everyone goes about their work. Where else do you see this? No one has the time to see the new visitors. It may not be high-end and perhaps looks difficult and boring, but people are involved in whatever they are doing.

A person (living in such circumstances) has two options -- behave like a victim and blame, complain and turn to violence, or take matters into their hands and lead one's life and make it better.

The people in Dharavi have opted for the latter. The people there have a sense of community, awareness and belonging.

Dharavi, in a way, gives them a sense of identity and there is pride in what they do.

Sure, it looks hellish and it definitely is, but human beings are flexible and they adjust and recalibrate their attitude to suit the conditions and find whatever sources of happiness they can within that situation. That is something!

Dharavi has two prominent communities -- the Muslims and South Indians. Could you tell us a little about the dynamics that these communities share and how they have evolved?

Surely, over the last 20 years (after the 1992 riots) there has been some polarisation. And though the riots were not repeated, the areas of which community lives where have been more or less demarcated. However, they continue to live peacefully and do business with each other.

'Dharavi can exist without Mumbai, but I don't think Mumbai can without Dharavi'

What were your greatest learnings from your numerous visits to Dharavi?

I think the greatest learning was that you can always create something out of nothing.

The second learning was that you don't need to have a lot of possessions to be happy. They may desire to have more and better, but you realise they don't lack anything; they have some kind of internal source of happiness and are quite content in many ways.

The third learning was that nothing in Dharavi is wasted. We can only talk of being eco-friendly. Dharavi is extreme in terms of the eco movement. Almost all our plastic waste goes there and is recycled and reused. The fact that you can extract an economic value from what looks to be waste was a revelation.

We often tend to judge people by their appearance, but from the stories we came across, the greatest learning was that there is potential in everyone. There is always more to things than the eye can see. So many of us (and I am guilty of it too), often put so much importance on degrees and grades and appearances, when there really isn't any need for it.

Tell us then of the things you 'unlearnt'...

First, you must stop looking at the physical reality. Of course it is dirty and congested and all of that, but there is more to Dharavi than that. If living in Dharavi was so horrible, people living there should have gone somewhere else, shouldn't they? What your eyes can see is not necessarily the whole picture.

Till I visited Dharavi, I always thought of people living there as encroachers who didn't have legitimate rights to be where they were. I never thought of them as making a contribution to society.

Like most people, I never met those who lived there or understood their problems. I never gave it a thought.

Most people deal with slums by situation -- by ignoring them -- but I think everyone is connected to it and if Dharavi was to be taken away, it would affect everyone in Mumbai.

Dharavi can exist without Mumbai, but I don't think Mumbai can without Dharavi.

'We would rather have more people understand and learn about the issue than just research scholars'

How long did it take to write this book?

We started work on it in February and decided that we would go ahead with whatever material we had collected by December 1.

Were there any stories you didn't include?

Of course, there were a lot of stories, but that was because we didn't want to throw a tome at our readers.

A subject of this nature does not have an appeal to the readers of my books and it may have been difficult for them to relate to the people we featured.

We were aware that none of my readers faced the kind of problems that those in the book did and it is not a natural subject to my readership. But that was the challenge -- to get people who would otherwise never read about this subject to read this book. We did not write 'Inspiring Stories of People from Dharavi' on the cover, because the book is not just about that. We do cover background and other issues.

For our learning, background and understanding, we did delve into the subject much more. We chose to highlight the positive; explained what Dharavi is and that it is difficult to live here, but despite that people are doing these interesting things.

Dee, the photographer, also travelled with us and shot pictures of the people we were interviewing. The way the book is designed -- it looks almost like a magazine in a book format -- is, in part, because we hoped to make it look well-presented and appealing to my readers.

We would rather have more people understand and learn about the issue than just research scholars. Somewhere, I suppose, we also hope it reaches the people who can really make a difference, who can perhaps replicate some of the things that exist here in other places where we look at entrepreneurship.

'Visiting the place over and over again was a little depressing'

How did you go about selecting the people you featured?

We wanted to represent the broad set of industries that exist in Dharavi -- leather, garment, food, recycling, social service etc.

The people we feature are symbolic of some thought or idea. These are the ones who, I suppose, had the 'X' factor and stood out and grabbed you.

What was people's reaction to being featured in a book?

Most were kind and friendly. It is not difficult at all to meet people. I guess you have to build a rapport with people, who then introduce you to other people.

What were the challenges you faced while writing Poor Little Rich Slum?

For starters, we didn't know anyone so we didn't know where to start. Also, just visiting the place over and over again was a little depressing and sometimes it made you wonder about why people have to live like this.

At some point I wasn't sure if we would get what we were looking for. Deepak certainly believed that we would and we did end up meeting a lot of interesting people towards the end.

What is your next book about?

I am working on a book on women entrepreneurs. Besides that, there are a few other projects in mind, as also another project with Deepak.