| « Back to article | Print this article |

'I feel like I'm trapped in a dream within a dream'

My mom cries every time she hears it. They're honoured; they love it, and I think the greatest moment for me with this album was getting invited to be a musical guest at the White House for Diwali. My mom was sitting right there and it was a proud moment for my parents because they came to this country with nothing and they never would have imagined in a million years that one day they'd be sitting in the East Room at the White House -- at a Diwali celebration no less -- watching their son sing a song that he wrote about the sacrifices they made as Indian immigrants."

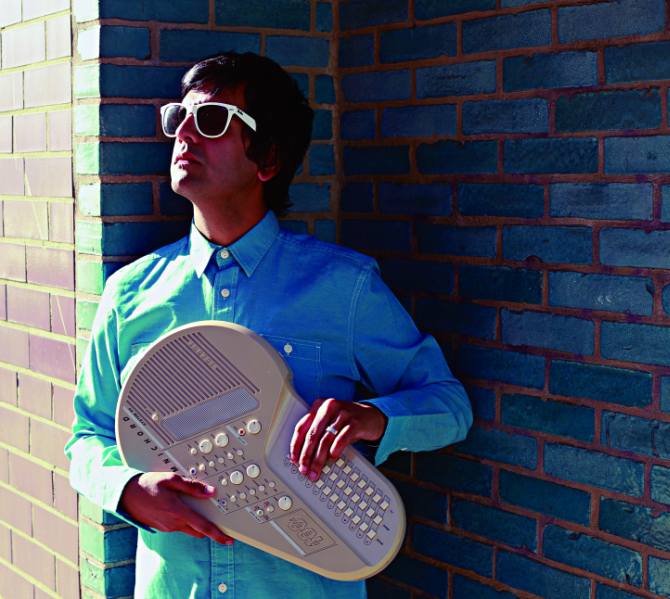

Siddhartha Khosla of Goldspot, a rock band in America, chats with Chaya Babu about his music, his separation and subsequent reunion with his parents as a child and that all-powerful motivator called acceptance.

Siddhartha Khosla was in eighth grade when he performed a Hindu spiritual song in an auditorium of over 400 students during the annual cultural diversity week at his New Jersey middle school.

"I sang in Hindi," he recalled. "Some bhajan. I was in a kurta pyjama and I had my harmonium. I think I had just gotten braces. It was very awkward. And the kids went nuts. For the rest of the year, they'd come up to me and recite the lyrics; they remembered the hook of the song and they'd sing it back to me. They weren't making fun of me. They loved it."

|

Similar to a lot of young Indian Americans like himself then, Khosla had that thing, that weird thing where he was Indian but not and American but not and somehow each of those things negated the other one just a little.

But when his classmates identified him in the hallways with the 'Bolo Ram Bolo Ram' that stuck with them -- because it was catchy, because they thought it was cool -- just like that, Khosla stopped the code-switching between his parents' English and his peers' English depending on who he was speaking to.

"I was like, 'Hi Mom, how arr yoo today, how is eewrrything going?' and I'd go to my friends and be like, 'Yo man, what's goin' on?' and I'm not sure my parents even noticed," he said. "But then I got to bring my culture to this audience of kids who in my past had always been not-so-accepting or cruel. When those kids, who were mostly not Indian, accepted what I was doing -- I mean I couldn't have done something more Indian -- I felt comfortable in my skin. I felt like I was accepted for who I was."

"I think when we feel accepted for who we are, it opens so many doors. It allows us to really be ourselves. Sometimes you need to feel accepted to behave like yourself."

With that, he let himself be Indian to his American friends, and American to his Indian family.

But for Khosla, this moment wasn't just a turning point in embracing his multi-faceted identity; it was also when his singing crossed over from something he did at the temple on Sundays after practicing the lyrics and tunes to prayer songs all Saturday, to something he did in a band that rehearsed in friends' garages. A band called The Hip Hop Hindus and the Jumping Jew, but a band nonetheless.

His friend, older and cooler friend Sanjay Sethi, who later became his brother-in-law, which is how Khosla refers to him today, saw talent and invited the young bhajan belter to join him and a few others in a venture that meant playing mostly for that same school audience.

Of course this meant Khosla had to make his first foray into Western music, which he had somehow not gotten into before he was 15. His old-school boombox, double cassette player and everything, was set almost permanently to play his mothers tapes -- mixes of classics by Kishore Kumar and Lata Mangeshkar that he crooned as he mimicked the only songs he knew -- and one day, on impulse, he flipped the switch to radio.

REM's Orange Crush blared from the speakers. Though the spirit of rock and other American genres had likely been swirling in the air around him for years, playing in the bedrooms of the same kids who dug his Bolo Ram, the sounds were new to Khosla. But soon after came his passion for The Beatles, The Cure, The Smiths, New Wave, and more. His band did INXS, Morrissey, and Red Hot Chili Peppers covers.

"I even rapped once," he laughed. "Oh it was terrible."

Perhaps. But Khosla's background of loving and learning to play music from opposite sides of the world informs his craft today. He describes his song-writing as drawing from both an old 1960s Hindi vocal melodic sensibility that was the backdrop of his upbringing as well as from indie rock elements that his fans mostly likely associate with Goldspot, his present day band.

And the sound he has created, a melding of styles though certainly not 'fusion,' is reminiscent of the cool, retro harmonies of The Beatles.

It has attracted a loyal following and received critical acclaim: Los Angeles Times music editor Loraine Ali named Khosla's most recent record, Aerogramme, the #1 album of the year last year and The Sunday Times wrote of the band, 'Who are they? One of the best new bands to come out of America in years.'

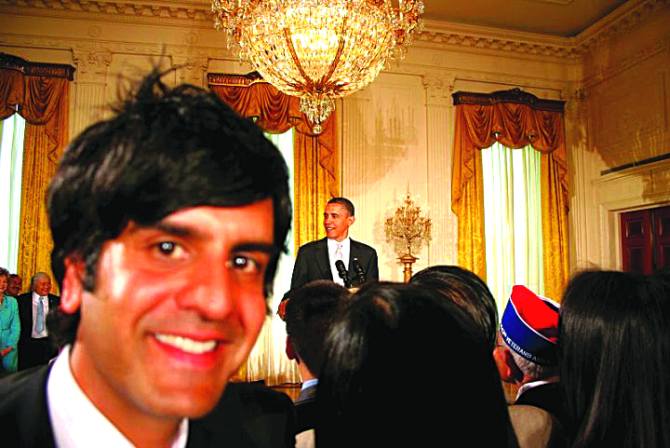

Probably most notably, at least to Khosla, Michelle Obama invited him and bandmate Jake Owen to perform at the White House Diwali celebration last year.

Please click NEXT to continue reading

'My mom would send me a cassette tape with her voice telling me she loved me...'

In the veranda in the midnight heat

Cousins and I would wait for the rains;

Singing songs about America and then the first drops came.

So don't worry, even though you were oceans and continents away;

I heard evergreen hits, lullabies and everything you had to say.

See mother I believe

That half of everything I hear is true;

Between you and me I believe the anecdotes too

If they get you through...

If time, time could be bent with the drop of a tear

You'd see it rained in our house for a year;

And this is the sound of the beating you'd hear....

On the tapes we've taped over all of our hopes and our fears

The open veranda's been flooding for years

I always hoped that I'd see you here

Evergreen Cassette was one of the three songs that Khosla and Owen played for Mrs Obama and her guests. From Aerogramme, the piece fits with the theme of Khosla using his music to tell an autobiographical story -- one of family, migration, displacement, and distance.

"I was trying to remember stories from my childhood and put them into this album," he said.

The result is a heartfelt collage of vignettes from Khosla's early life in the United States and India as well as small representations of what it meant to be the child of immigrants.

His parents came to Connecticut in 1976; though privileged with their scholarships to Yale Law School and Medical School, times were still hard -- working full-time while completing their schooling and having arrived with the classic meagre $8 in their pockets. Then Khosla was born. They realised it was nearly impossible to focus on the American Dream if they couldn't also care for him. So, they saved up to take him back to India, where he lived with his paternal grandparents for a few years.

"At the time it was $24 a minute to make a long-distance call from US to India," he explained. "So my mom would send me a cassette tape with her voice telling me she loved me, and I would hear it and say something back, probably unintelligibly, because I was so little. But I got to hear her voice, and we did the same thing, back and forth, over and over again for two years. There was something beautiful about that memory to me, so the song on the album called The Evergreen Cassette is actually about that story. She still has the tape, but she won't give it to me I think because she's scared I'll lose it."

Even with all the way stories of the Indian Diaspora are being documented, Goldspot's take is fresh and inventive. The melodies and instrumentals rouse nostalgia for the era when a major wave of immigration was taking place, but the voice is current, youthful, rock-inspired, second-gen.

The record is full of all kinds of lyrical snippets about this phase of Khosla's family's life, stringing together disparate pieces to create a rich narrative about India and America and who and what was in between.

New Haven Green tells of letters his father penned on paper napkins to faraway loved ones, but never sent.

Resident Alien is about the first time he went through his mom's wallet and found her green card; he was appalled by oxymoron and the fact that a person could be given such a label in culture where aliens are ubiquitously seen as enemies.

In the same song about the cassette tape is a mention of a veranda that Khosla remembers from the Shaktinagar, Delhi, home of his toddlerhood, which serves as the central basis for another track.

The Monkey on my Rooftop depicts a vivid recurring scene of his grandmother shooing away a monkey who constantly showed up to eat fruit from their lychee tree.

"It was one of those houses, those tall rectangular houses that all butt up next to each other and there was a roof that you could access and fly kites from," he said. "You could really jump over to the next person's roof if you wanted. The house effectively had a square hole in the middle -- from the roof, if you looked down, you could see a square cavity that went down to the open veranda. So it would rain in the house. At the base there were marble floors and there were glass doors to access the rest of the house. But I remember my chaachi (paternal uncle's wife) going up to the roof all the time -- she would beat the shit out of the monkey with a broom and the monkey would come back."

These are the moments that shape Goldspot's year-old masterpiece, their third album after other successes. But because of Khosla's candour and authenticity, this record is also a work of art that freezes in time through song experiences relatable to anyone of any generation whose life is in both India and America, even if only in their consciousness. After all, not all of us split our childhoods between two continents.

Because of his somewhat rare set of circumstances, Khosla described his dual identity as seamless, versus fractured, a concept frequently applied to the Diaspora. He returned to the US when he was 4, upset to have to go back to his parents. At that point, he likely didn't remember them at all, apart from the voices on the evergreen cassette.

"That's something my mom grapples with to this day, and I think there's a certain regret there that they had to send me away so they could bring me back," he said.

Please click NEXT to continue reading

'The 20-something-year-olds in us wanted to drink the same water as our British idols'

It was 1980. At this point his father had completed his LLM and JSD degrees, and his mother was done with her residency. But times were tough. His father's hunt for a university position was wrought with discrimination -- there so were few Indian law professors at the time that when he finally did establish his career, the professional association he became a part of had its annual conference in the apartment of one of the members.

"He graduated from Yale with a doctorate in law from arguably one of the top law schools in the world but he couldn't get a job teaching anywhere because no one would hire him. Their eyes weren't trained to look at an Indian man and say, 'Yeah you can be a law professor.' They hadn't seen it. It was not a part of the culture. He'd walk into Columbia, NYU, all these places for interviews, and at one interview they asked him, 'So you're here for the TA position?' My dad's like, 'I'm a published author. I'm a doctorate. Why would I be a TA?'"

This meant accepting a job in Florida at Nova Law School, while Khosla's mother remained in Connecticut. But they made it work.

The father-son duo drove every month from Fort Lauderdale to New Haven, stopping on the side of the road to sleep and then keep going, only sometimes staying the night at a hotel. This arrangement didn't last forever of course.

Eventually, everything aligned and they all moved together to Tenafly, NJ. Khosla's mother joined an OB/GYN practice and his father got a job teaching at a CUNY law school, where he continues to work today. Soon after Khosla had a baby sister -- the one who is now married to his friend and influencer Sanjay Sethi.

"Sanjay and I stayed in touch through college and he was always the one who got me into new music," Khosla said. "He got me into Radiohead and every single band I ever liked. He was older than me, I looked up to him. His musical taste was always great, and he was the one to always be like, 'Check this out, check that out.' So at the end of college, Sanjay called me and, again, was like, 'Look we need to start a band.'"

Khosla's involvement with music grew while he was at the University of Pennsylvania, despite being passionate about his studies. He majored in history and political science, spent a summer working for the Public Defender Service in Washington, DC, and even ended up taking the LSAT. But his time at the Ivy League institution, one known for it's a capella greatness, was a major step in solidifying his singing and song-writing career.

He joined a group called Off the Beat. It was the No 1 a capella group in the country at the time, and Khosla became somewhat of a campus star through this. He jokingly mentioned his social transition from feeling like a dorky high school kid to a guy who people knew at Penn and wanted to know, a guy who girls actually paid attention to -- he met his wife, with whom he now has a seven-month-old daughter, in the final days of his senior year and then went a whole decade before reconnecting with her in New York and starting to date.

Throughout this time, his understanding of music reached a new level.

"I would write arrangements for the group," he said. "I'd have to listen to a song and make it into an a capella arrangement for us to sing. I'd chart out the notes that were being covered by the guitars or the piano -- every single note that you hear, someone's gotta sing that. It's very complex. I learned so much about music in the process. It almost feels like you're a composer. Even though you're taking an existing song and working with it, you have to write new parts. The writing was a really big part of learning how to orchestrate things with an ensemble of people singing what you arranged."

With only 6 months of real formal musical instruction in middle school, his role in Off the Beat became second nature to him, and during his senior year, he was asked to be the musical director for Penn Masala, the wildly popular Hindi a capella group, which was just coming into being as he was on his way out of Penn.

It was then, around the time he cancelled his LSAT scores, that Sethi convinced Khosla to make the move to London. To give the music thing a real shot.

Why there? Why not when all your idols are British.

"The 20-something-year-olds in us wanted to drink the same water as them or something," he laughed. "But I'm glad we did. We both got jobs as bartenders, and we both got fired. We didn't know how to make any drinks. We had a little one-bedroom apartment that we shared, and we had a little Tascam tape recorder and we just started writing songs."

They wrote six songs and made a little EP out of it, but Khosla said at that point what they created was much more in the direction of fusion music and he felt it was no good; that gave him a starting point to develop his own individual sound more fully and depart from much of what he'd done before.

Their visas expired and they moved to Los Angeles, where Sanjay left to pursue other work, making the duo a solo act.

Please click NEXT to continue reading

'My mom cries every time she hears it'

Khosla spent his time outside of his day job at AT&T meeting new musicians, building his musical vision, playing multiple times around the city, and learning how to play every instrument in what would end up being a band of rotating team members with Khosla as the lead. After a year, he got a deal with a small independent record label.

Things picked up when LA radio station KCRW DJ Nic Harcourt got his hands on Tally of the Yes Men, Goldspot's first album, and fell in love with the track Rewind. Khosla said he played the song nonstop, leading 10,000 copies selling in two months in California alone.

"Nic was considered then to be the ultimate tastemaker in radio in the US," he said. "He was so influential. He was the first to play Coldplay, Moby, and all these other great bands that ended up becoming huge. It was my dream to get played on that station."

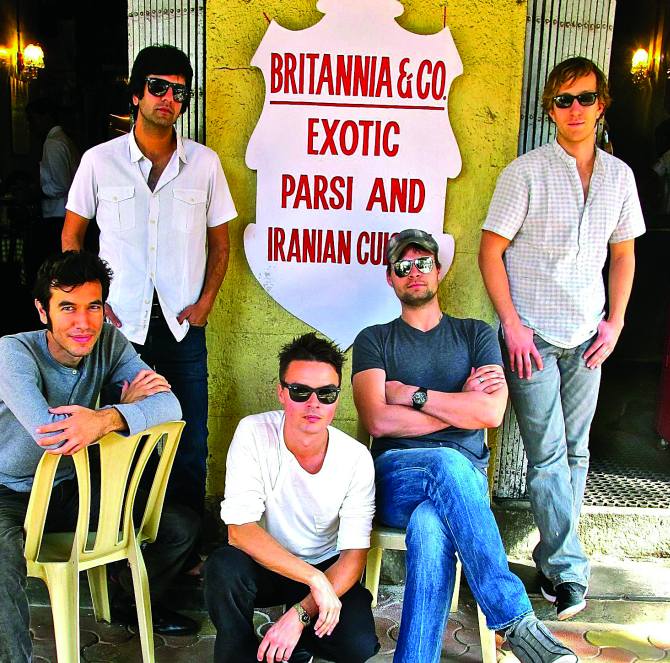

Then London happened again. Scott McLaughlin, who also signed and manages current New Zealand pop sensation Lorde, signed Khosla to Universal Music Group, which released the Tally of the Yes Men across the Atlantic through Mercury UK. So Khosla moved back again and blew up in the indie rock scene there, hearing his songs make the Top 10 lists on the radio, playing on the same bill as Bjork, The Arcade Fire, and Death Cab for Cutie, opening London's O2 Arena for the first time ever in front of 20,000 people, getting praised in print on front page of The Sunday Times, seeing his Friday video follow Rihanna's Umbrella on music channels, and more.

"It did so well; it was great," Khosla said. "It was so flattering to hear what critics had to say, and it feels cool even now, but it also created this unrealistic expectation. You know, I was just this band from LA and got transported to the UK where we had no fans. We were just getting fans in the US -- that's what we were building, and all of a sudden the label moved us out and tried to start us fresh there. In the process I didn't build on what was happening here. So people here were like, 'What happened to Goldspot?' I'm sure we lost some of our fans through that. So those big experiences were amazing but that was also short-lived."

Tally of the Yes Men flopped in the minds of the label heads, however. It was a rough time in the music industry, as sharing tracks and whole albums digitally became the norm. The album sold, but not enough to warrant Mercury putting out another. Khosla feared that they would take the album he was working on then and simply shelve it, the fate of many artists in his position.

He left voluntarily, on good terms, returned to LA, and released And The Elephant Is Dancing on his own (he started a label with manager Steve Nice, Mt Hoboken Records/Nice Music Group). Featured on television and radio, in film and advertisements, the album secured Goldspot a place in the US indie rock scene again. With the massive shift in how the music business works, the band's songs appearing repeatedly in How I Met Your Mother, an iPad commercial, and more has garnered lots of fans for Khosla, in a way that makes him measure his success differently from how he might have 10 years ago.

"It was so incredibly un-cool before to put your music in some of these places," he said. "Pearl Jam would have never used their song for an ad when I was in high school. They would have scoffed at the idea. I think now they would do it."

Just the fact that Khosla can mention an act like Pearl Jam as he reflects on his own career choices is huge considering his father worked to occupy a professional space that at the time was unfathomable to many Americans.

Other young rock-loving and music-minded Indian Americans speak of the lack of brown faces on the stages at concerts or on MTV in the '80s and '90s -- how this impacted their sense of possibility, their sense of identity. Khosla changes that.

Aerogramme has been another huge hit, with the press eating it up -- The Los Angeles Times endorsement was no light statement -- and shows booked through the summer. Goldspot may even end up touring in India later this year, where they have been invited to play at a college festival in Rajasthan.

Khosla said the fans there are hungry for the band's sound: "Kids in India connect with the music on a totally different incredible amazing level. It's honestly so cool. We headline music festivals and play for like 5,000 kids in Lucknow. And then pack venues in Delhi and Bombay and Hyderbad and Bangalore. The kids there are just so passionate about this band. It's an escape from Bollywood, but it's also theirs; they see an Indian guy and they feel like it's their indie rock band."

They're not the only ones. Khosla's family, unsurprisingly, is moved by not only his success but by the way he has used music to hold on to his roots and bring his family's story to the public. Aerogramme was his attempt to pay homage to the journey his parents made in a very original way.

"My mom cries every time she hears it," he said. "They're honoured; they love it, and I think the greatest moment for me with this album was getting invited to be a musical guest at the White House for Diwali. My mom was sitting right there and it was a proud moment for my parents because they came to this country with nothing and they never would have imagined in a million years that one day they'd be sitting in the East Room at the White House -- at a Diwali celebration no less -- watching their son sing a song that he wrote about the sacrifices they made as Indian immigrants."

"In my mind, there are just so many layers to that. I feel like I'm trapped in Inception or something -- a dream within a dream. There was magic to the whole thing."