| « Back to article | Print this article |

All things spice: Tara Deshpande's journey from the cinema to the kitchen

Actress-turned-chef-turned-author Tara Deshpande's book on Konkani cuisine is a fascinating account of a family's love for food.

Through recipes and a memoir-style introduction, it harks back to a simpler world and attempts to hand down fond memories of teas and breakfasts, lunches and dinners to a new generation.

Deshpande talks to Rediff.com's Abhishek Mande Bhot on the importance of documenting food and just how she came about to fall in love with India and its cuisine from her grandmother's kitchen.

Tara Deshpande lugged her suitcase along the Boston Metro Rail system, changed two trains and made her way to Harvard Square. She walked down Brattle Street, once home to George Washington and Henry Longfellow, and entered an imposing colonial mansion where the American feminist Margaret Fuller lived for a while.

Today, the building serves as a location of the Cambridge Center of higher Education which had hired the former Indian actress to conduct classes on Indian cooking.

"Someone thought it was a good idea to hire an Indian to teach Indian cuisine so here I was," Deshpande laughs as she recollects the very first cookery class she conducted there. She had never taught cooking before, though she had been an enthusiastic cook all her life. "I'd cook even when I was working (in the movies) and had very little time," she says.

This was 2002. The acting and modelling offers had practically stopped; curtains had fallen on Begum Sumroo, the play in which she played the title role and Deshpande had settled into domesticity in Boston with Daniel Tennebaum, her husband of two years.

The actress was playing out a role that seemed far cry from the rebellious characters she essayed onscreen when the teaching offer came along. It seemed like a fun thing to do and so she took it up.

"I was pretty confident before my first class; I thought I knew everything," she says sitting in her sprawling south Mumbai home that offers stunning views of the High Court and the Mumbai University buildings.

On the morning of the lecture, she had gone shopping for fresh ingredients, organising the printouts of her recipes and preparing for her first ever lecture on a subject she'd learnt largely by osmosis.

In the days to follow, most of that confidence would be shattered. "It is one thing to be a home cook and it is another to teach Americans how to cook." she says. "They are obsessed with portions and they like to have everything written down so they can replicate the dish over and over again. Half a cup of this and two tablespoons of that doesn't cut it with them. Indians cook by approximation, they don't."

Then there were questions that hadn't occurred to her in all the years of her cooking:

Why does one cook onions to the point of them being mushy in some recipes and leave them almost raw in some others?

Why does one add curry leaves to a tadka before asafoetida?

These and others would eventually force her to do serious research on the topic.

In any case, Tara Deshpande Tennebaum had passed the test and received positive feedback from her students at the end of her first lecture. Over the next few months, she would continue conducting classes on regional Indian cooking at the centre. When she focussed on western India, she made it a point to draw out the differences in the cuisines Konkan region from where she hails and Kerala.

"A lot of us like to believe that any dish that has coconut gravy in it must be from Kerala (or the south of India). I felt it was important to bring out that difference and I suppose that idea also became the seed for the book."

All things spice: Tara Deshpande's journey from the cinema to the kitchen

THE BOOK

A Sense for Spice is a fascinating introduction to the Konkani cuisine and includes traditional recipes that have passed down Deshpande's family. It is also in part the story of a family that has been passionate about cooking and eating good food.

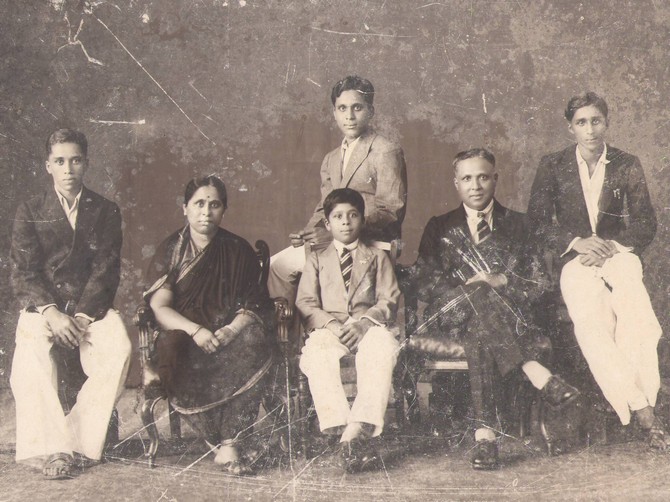

The first 80-odd pages are a first-hand account of Deshpande's growing up years and her maternal grandmother, Sarala Kamalakar Rao Kulkarni's kitchen becomes a microcosm of India's socio-cultural changes.

Written in an engaging style, A Sense for Spice takes you from the sleepy border town of Belgaum to the glitzy city life of Mumbai and paints an intimate picture of a family and its love for food.

It isn't surprising then that food means a lot more than just tossing up a few ingredients for Deshpande. Several of her early memories are associated with food. She describes one of them eloquently in her book:

I think I first fell in love with India and its food in Grandma's kitchen. It was a magical place. It opened every day with the first light of dawn. Sounds came in cosy, familiar sequences. I lay in bed, half-awakened by the whispers of Grandma's Chanderi sari and the sweet fragrance of her jasmine hair oil; by keys clunking and the kitchen door opening with a quiet creak; by the tinkle of cups and saucers, the gurgle of milk, the slurring of tea leaves against a sieve.

Cooking started in earnest only after the sacred ritual of tea. The house resounded with the jangle of bangles on grandma's arms as she flitted from one pot to another, soothing, coaxing, and nudging nature's bounty into its proper place.

Then there was the time when her grandmother taught her to roll chapattis when she was all of six and add tadka when she was seven. "I remember standing over a tiny stool so I could see the ingredients that were going in," she recollects.

It is obvious that her mother and both her grandmothers -- the maternal one more so -- have had a significant influence on Deshpande's life.

"I was told that my mum could make a complete meal when she was all of six. I wanted to better that; obviously that wasn't possible," she says. "Both my grandmothers were great cooks, though in vastly different cuisines. My father's mum was more sophisticated because she led a city life and cooked fancy international fare. Can you imagine we would have tempura and sushi at home back then!

On the other hand my maternal grandmother was more inclined towards Karwari and Konkani food. My mother expanded on both their repertoire and I took over from her."

All things spice: Tara Deshpande's journey from the cinema to the kitchen

FOND MEMORIES OF SIMPLER TIMES

Deshpande describes what must have been the most magical years of her growing up life -- the vacations she spent with her grandparents in Belgaum where they had settled after her grandfather retired as an admiral from the Indian Navy.

It is evident her maternal grandparents were among her most favourite people. She writes of them:

Grandma and Grandpa had been childhood friends, as had their parents who lived in Dharwad. They came, as did thirteen generations of my family tree, from the same community. Every summer when school was out, the kids in the neighbourhood gathered to play in Grandpa's father's orchard.

Grandpa was a bully and grandma didn't like him. He tied her pigtails to various objects: chairs, railings, tree branches, even a cow's tail. Eventually they tied the knot. But of course, it was a very correct 'arranged' marriage. Arranged by the two of them

Deshpande speaks eloquently of her times there, of the fruits from their orchards, 'spices that were ground, sprinkled and massaged into onion pastes to create curries' and 'rustic wooden cabinets that were chock-full of treasures'.

She says of those times in the book:

When we unearthed such treats, we had to ask permission to consume them. Often, we received an indulgent 'go ahead', and enjoyed them at the dining table with everyone, but sometimes, the answer was a definite, 'No - it's for next month' or 'No, that's for Mrs Kumble's luncheon.'

So, to our infinite disappointment, we didn't get to eat them, at least not at the dining table, but clandestinely, in the wee hours of the night or during the family's afternoon naps.

Often the findings, contained within a drum or a heavy glass jar, were too large to move out of the kitchen, so the cousins took turns bringing bits and pieces into the bedroom.

On days when grandma was out at a party or busy in the garden, we went in threes; tow climbed into the vast cupboards and ate to their hearts' content while a third stood guard.

If an adult was seen in the area, the watchman had a vigorous bout of coughing. One summer, cousin Vimal found himself a jar of plums soaked in brandy. He didn't share them with us. He tottered a bout so alarmingly after this dessert that we locked him in the kennel until he'd slept it off.

All things spice: Tara Deshpande's journey from the cinema to the kitchen

AND THEN I MOVED TO BOSTON

By 2000, these simple times were behind her and Tara Deshpande was in Boston happily married Daniel Tennebaum, an equity consultant who she'd met during his sojourn to Mumbai. "Around 2002 Daniel had taken a break and had gone back to school; I had completed my (acting) assignments and wasn't travelling to India anymore. I was away from my family and friends and there was nothing for me to do in Boston."

The teaching assignment at the Cambridge Center led to similar assignments at other schools and eventually an order to cater for house party from one of her students.

"Around 2004, I had begun catering occasionally from home. But when the first big order came in -- to cater for an event of 350 people -- I knew I'd have to move to a professional set-up.

At some point I also realised that to understand my own (Indian) cuisine better, I needed to understand other cuisines too, why people eat what they eat… just to get a perspective."

This quest led her to several institutes including what was then called The French Culinary Institute in Manhattan and Le Cordon Blu in Paris. She took classes in regional French cooking, desserts and patisserie, pastas, fritters, donuts, macarons and even one in bread making. In between all these, she even went to Thailand to understand its cuisine better.

"When I was in New York, he would travel there on weekends but mostly we were based out Boston because my business was based there."

And it was booming.

"I was catering to much larger events including at the Boston Convention Centre where I would be making as many as 15,000 meals," she says.

By now, Deshpande was also writing about food and restaurants for Boston Globe and Boston Herald among other publications AND learning as much as she could at some of the best culinary institutes in the world.

It was while she was in Paris that she discovered the need to document one's culinary history.

"I would be affronted each time people would hold the French cuisine in high esteem. Ours is a much older culture and is vaster in range than the French can ever be. But I realised that unlike them, we never documented our (various) cuisines. Most of it was passed on through oral tradition. The French on the other hand have put everything down on paper. It is amazing the extent to which they've documented their food!"

This, she adds, was the other reason for putting together A Sense for Spice.

"We just need to put down the things we know so the generation after ours has something to fall back upon, to look back at," she says.

All things spice: Tara Deshpande's journey from the cinema to the kitchen

LIFE COMES FULL CIRCLE

When life offered an opportunity to return to India, Tara Deshpande took it at the drop of a hat. "Daniel received an offer to set up his company's office in Mumbai. He was excited but I wasn't sure if he'd like it here. But it's been three years now and he loves every bit of it.

He's beginning to love cricket and he's learning Hindi. The only thing he is finding it hard to cope with is the heat because he's spent most of his life in Minnesota where it is cold."

It took Deshpande some time to wrap up her affairs, sell off her catering business in Boston and return to the city from where she began.

She's currently working on her first novel, which according to her is 'a political parody told from a woman's point of view' and 'negotiating offers for a television show'.

"This is home," she says. "It feels good to be back."

***

Few weeks after we first met I called up Deshpande for a round of follow up questions to realise that her grandmother, now 90, had been wheeled into the ICU only days ago. It is the first time she's had to be hospitalised.

Deshpande concludes her elaborate introduction to A Sense for Spice thus:

The year Grandpa died, my grandmother decided she would never cook again. I began, at this time, to cook with greater purpose. I think I had a subliminal need to preserve family traditions, so many of which have roots in our kitchen.

In many ways then, this book is also an attempt to keep some of those traditions alive, to hand down fond memories of teas and breakfasts, lunches and dinners to a new generation that may draw upon them and perhaps add some of their own.

A sense for Spice by Tara Deshpande Teenebaum is available on Rediff Books and can be purchased here.