He was toothless, with his hollowed cheeks and gaunt body giving him an ascetic look, and he moved his lips constantly, as if he was saying a prayer.

Until I entered the house, I'd been thrilled and was looking forward to this encounter. Surely, I thought, the newspaper Nana read every day would be eager to publish my grandly titled 'Interview with the World's Oldest Man'.

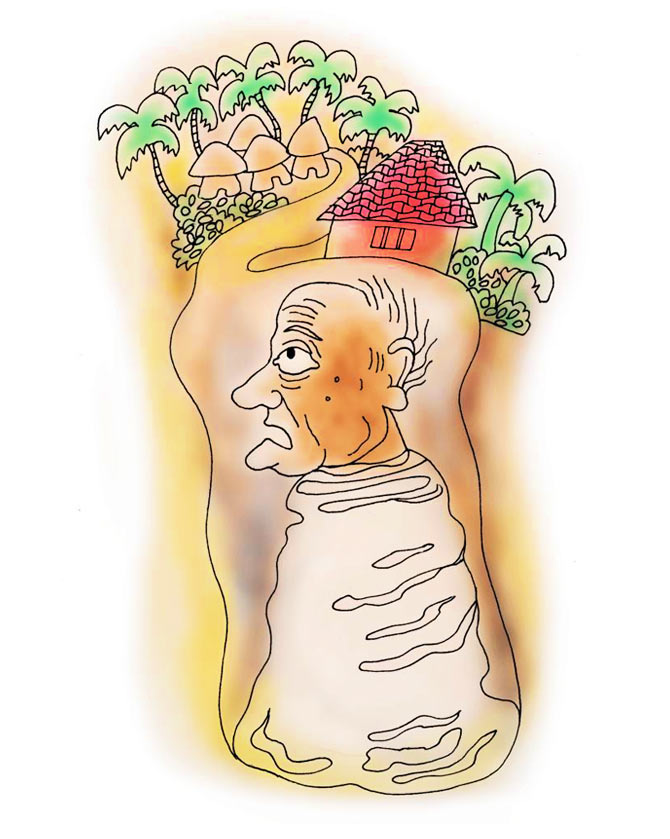

A heartrending story of Murali Kamma's attempts to interview an old man. Read on

What are you reading?" my father asks. Twice. Actually, I've stopped reading -- I'm tired, having returned home late the previous night -- but my head is bent low over the newspaper on my lap, and Nana, from where he sits in his recliner, can't see that my eyes are closed. Shaking off my drowsiness, I look up.

"It's today's paper, Nana. Would you like me to read from it?" Until his health deteriorated, my father had been an avid newspaper reader. For as long as I can remember, even when we travelled in India, he'd never fail to pick up a daily paper -- and sometimes, if we happened to be in a remote place, he'd pay to have an English-language paper sent to him from miles away.

"Let's talk," he says. "It's pretty quiet here, you know."

"Of course." I feel a stab of guilt. "I wanted to come earlier, but there was an unexpected business trip. Sorry. Is this place working out for you, Nana?"

|

He doesn't answer. Does that mean "yes" or even "not sure," rather than "no," as I hope? Whatever he means by the silence, I'm glad to leave it at that for the moment. What choice do I have, anyway? I often think I should be a good Indian son and keep him home, like my sister did, and do all the right things -- but then the thought overwhelms me and I push it out of my head.

"Is there any Indian food you crave, Nana? I'm sure they won't mind if I bring it. I can check with them."

"Forget that." He waves dismissively and then points at the newspaper on my lap. "Anything interesting?"

I'm struck by how frail he's become in recent months, with sagging cheeks and sallow skin, and I notice that his weathered hand is trembling. With his unshaven face and wispy, uncombed white hair, and a crumply shirt that's too big for his shrunken body, he seems a little lost. His eyes are glassy and his mouth twitches. I wonder what I'd find in the doctor's latest report.

I'm about to speak when a mechanical roar stops me, drawing our attention to the window. A lawn mower appears close to the building. A man with an impassive expression, wearing sunglasses, is standing erect on the mower, and for a few moments we only see his upper body, moving left-right-left like a juiced-up robot, before he disappears from view and the sound fades.

"I was reading about the First World War -- or rather, the centennial remembrances of the war," I say, folding the paper. "Do you know what it reminds me of?"

He looks puzzled. "Did I have my lunch?"

"I think you did, Nana. I saw Alex removing your tray when I got here. Are you hungry?"

"No. Just checking. Sometimes I forget, you know. How's Rita?"

"Gita is fine. She said she'd visit you this weekend with the kids."

Recalling the night Gita and I quarrelled, after my late return from a business trip, I wince inwardly. I was exhausted -- and, of course, so was she. Tempers flared, voices rose. And though the bedroom door was closed, I doubt that it prevented our shouted words from escaping down the stairwell in a mad rush and enter, like a rude intruder, the room where Nana was sleeping.

"What do you want me to do? Should I quit my job? I know it's a burden for you…"

"I didn't say that. But it's too much…I can't handle it. The help I'm getting is not enough. We need to do something."

"We will…this is temporary…"

Just a day later, when I walked into Nana's room with his cup of coffee, he said he was ready to move.

"Move where, Nana?"

"Old people's home, assisted living, nursing home, whatever you want to call it. Where else?"

My attempts to allay his fears and delay the inevitable didn't work -- and before I left the room, I knew he wasn't going to budge from his decision. Within a few weeks, our house was no longer my father's home.

"The paper," Nana says, pointing again, and for a moment I think he wants to look at it. But, no, he's asking me to go back to what I was saying about the article I'd read.

"Well, it talks about how the First World War is being commemorated today, a hundred years after it broke out. It brought back memories of my interview. Do you remember that?"

"Yes," Nana says, surprising me. And he smiles at me for the first time that day.

* * *

When I was growing up in India, Nana had casually mentioned one day -- as he was reading the paper, I recall -- that one of the world's oldest men lived in our ancestral village.

Stunned, I asked, "Nana, how do you know he's the oldest man in the world?"

"I said one of the oldest, not the oldest. But who knows? When I was a boy, I heard that he'd gone to Europe as a British Indian Army sepoy and fought briefly in the First World War. What's astonishing, though, is the claim that he belongs to Mahatma Gandhi's generation."

I felt my spine tingle when Nana said that Gandhi was born in 1869!

"Can we go to the man's house?" I said. "I want to interview him." My vacation had just started and we were going to visit our ancestral village the following week.

My mother, who'd overheard the conversation, stepped out of the kitchen and said, "We'll see… don't get your hopes up. The man is old and not well. I don't know if he'll be able to speak."

But he did speak, briefly. Nana made inquiries and, after getting permission from the old man's family, took me to see him at their house in the village. We set out one morning, to the sound of chirping birds, and walked along a gravel road that skirted green paddy fields shimmering in the sunlight. Although it was summer and already quite warm, a lively sea breeze -- which made the coconut and palm trees on the way sway decorously -- prevented us from sweating.

The road curved and went past thatched huts, where farm workers lived, before ending near a banana grove -- behind which was a modest house with a sloping, red-tiled roof. We stopped there and my father knocked on the door.

A middle-aged man greeted him respectfully and led us to a room where the old man, shrivelled with age, lay on a narrow bed, staring vacantly at the ceiling. He was toothless, with his hollowed cheeks and gaunt body giving him an ascetic look, and he moved his lips constantly, as if he was saying a prayer. Until I entered the house, I'd been thrilled and was looking forward to this encounter. Surely, I thought, the newspaper Nana read every day would be eager to publish my grandly titled "Interview with the World's Oldest Man."

Now, becoming nervous, I wasn't sure if I could pull it off. The bulky tape recorder in my hand looked absurd. I wished it was less conspicuous, allowing me to slip it into my pocket.

Memory can play cruel tricks. It's so selective. The picture in my mind of our walk that lovely morning remains crisp, but it becomes blurry when I try to recall what was said. Perhaps the mood shift, from excitement to anxiety and embarrassment, had something to do with it. Nana had supported me, even reminding me to ask questions, but I don't recall opening my mouth.

The old man had rheumy eyes -- he might have been sick, not to mention deaf -- and what I remember most is his blank stare. We didn't spend much time there. My mother hadn't been keen on this outing, but Nana had indulged me -- as had the old man's relative, probably because my father's family enjoyed a high status in the village. Now, I felt sheepish about my intrusion.

But though I have no recollection of a conversation with the old man, it turns out -- thanks to the audio tape, which surfaced not long ago when I was going through Nana's things -- that we did speak briefly. The recording was a little scratchy, but I was able to listen to it after I found an old cassette player in the basement.

Me: "When were you born? Do you remember the date?"

Old man: "What? Who's this boy?"

The relative speaks in a loud voice.

Old man: "Oh, I don't know. Is that a camera?"

Me: "No, it's a tape recorder. What were you doing in 1947, the year India gained independence?"

Old man: "What? Is he taking a picture?"

Me: "No, this is NOT a camera."

Old man: "What?"

More loud talking, even shouting.

Old man: "Oh, I became a farmer after returning from the Europe War…"

Me: "You mean the First World War? How much older was GANDHI than you?"

Old man: "What? Who?"

Indistinct sounds, followed by loud talking.

Old man: "Don't know… never saw him…"

The recording ends abruptly.

* * *

Well, the other day, I found the audio tape of the interview," I say. "Nana, I didn't know you'd saved it."

He chuckled. "It was worth preserving, I guess."

"By the way, when Anita comes with her mother this weekend, she wants to interview you. She said that she wanted to ask her grandfather about his family history and childhood days in India."

"Good," Nana says. "She can bring her recorder, but tell her that I'm not the world's oldest man. Far from it."

My cellphone pings. Reaching for it, I see that there's a text from Gita.

"I'm sure you have things to do… you've been here long enough," he says. "You should go now."

"I will, Nana, I will." I put my phone away, but don't get up from the chair to leave -- yet.

Murali Kamma is an Atlanta-based writer and editor