| « Back to article | Print this article |

Father's Day: Nature's Top 10 Dads

Like humans, animals and insects too are equally protective about their eggs/offsprings/progenies. Check out these ten incredible examples of loving, warmth and care.

1. The Giant Water Bug

These insects are known to deliver a mean bite, which would explain why one of their colloquial names is toe-biters.

Although giant water bugs are considered a delicacy in Thailand and a pest in swimming pools across their habitat ranging from Northern and Southern America to Eastern Asia, down to Northern Australia, this fresh water insect exhibits a softer side that will make you go “aww” instead of “eww” for a change.

The male giant water bug, along with being a fearsome predator, is a caring and protective father who will carry a brood of approximately 150 eggs on his wings until they hatch.

Not only does the male carry the eggs around for about a week, he also makes sure to air them from time to time to prevent them from developing mould.

While cynics have termed children as burdens, the giant water bug sure does seem to carry his load well.

Father's Day: Nature's Top 10 Dads

2. The Emperor Penguin

For emperor penguins, when the mercury dips to minus 40 degrees celsius and the Antarctic winds are blowing at 120 mph, dads are the ones who come to their rescue.

Female penguins lose their nutritional reserves after laying the 460-470 gram egg and must return to sea for a two-month feeding period. Before the new mothers go away to replenish their nutritional reserves, they carefully transfer the eggs to the father. Although some couples drop the egg and lose the little penguin inside, the egg transfer is the least of the father penguin’s worries.

Papa penguin must then balance the egg on top of his feet, in his brooding pouch, all the while staying motionless in the face of 64 days of merciless winter waiting for the egg to hatch without letting it touch the ground, lest the chick inside succumb to the brutally low temperature.

Emperor penguin fathers huddle together with their backs to the wind in order to avoid losing body heat while incubating the eggs. Male emperor penguins lose up to 20 kg of body weight while caring for their young and end up at a meagrely 18 kg when the-64 day period is over.

The rigorous incubation period might be heavily taxing on male emperor penguins but one can easily assume that the adorable little fluffy penguin chicks that hatch out of it, make it worth the while.

Father's Day: Nature's Top 10 Dads

3. The Seahorse

Seahorse fathers have accomplished the impossible. Male sea horses can literally get ‘pregnant’.

Seahorses, found all over the world in shallow and temperate waters, exhibit a most unusual child bearing practice. The females of this species transfer between a few dozens to thousands of eggs into the male’s brooding pouch by means of an ovipositor.

The eggs stay inside the father seahorse’s brooding pouch from between 1.5-6.5 weeks during which the father seahorse nurtures the eggs by providing them with prolactin, oxygen and a safe environment, which is why litters of baby seahorses are often so large.

These tiny fish, ranging from between 0.6 to 14 inches, can give birth to a litter of as many as 2,500 live baby seahorses and they actually experience contractions.

Looks like daddy seahorses know exactly what labour of love is all about!

Father's Day: Nature's Top 10 Dads

4. The Marmoset

Marmosets, native to South America, are 8-inch long fellow-primates that can easily give humans a run for their money when it comes to childcare.

Not only do marmoset fathers care for their young but they also help welcome them into the world. Since childbirth is extremely strenuous on the female marmoset’s body, causing her to lose 1/4th of her body weight, male marmosets act as midwives to their mates, performing duties such as licking the baby clean and biting off the umbilical cord.

Father marmosets nurture their young even after birth. They groom, clean feed and carry their babies on their backs. However, since marmosets are known to typically give birth to fraternal twins, being the sole caregiver is next to impossible. Thankfully, marmoset dads have help at hand.

Marmosets do not live in single-parent families. Adult marmosets of both sexes (other than the parents) and older siblings also help the father marmoset in caring for the toddlers.

Although marmoset paternal care is known for its high level of concern for the infants, community participation is essential for raising young marmosets.

These primates seem to have realised a lot earlier than us that it takes a whole village to raise a child.

Father's Day: Nature's Top 10 Dads

5. The Greater Rhea

The greater rhea is a large flightless bird standing at 4.9 ft and weighting anywhere between 20-27 kg. Endemic to South America, they are polygynous as well as polyandrous.

An adult female greater rhea will mate with a male and deposit her eggs with him. The male greater rhea will then take care of the nest and incubate the eggs until mating with and collecting eggs from another female. A male greater rhea can end up with as many as 80 eggs from different females.

Greater rhea dads are responsible for everything from nest building to incubating the eggs with no help from the moms. Not only do they provide warmth and protection to the eggs but they also rear the chicks until the infants are up to six months old.

The male greater rhea may be the perfect caregiver to his child but the henpecked stereotype hardly holds. Greater rhea fathers become extremely aggressive if they sense danger lurking around their children and will not be reluctant to attack.

Taking fulltime care of his children as well as maintaining a harem of approximately 12 females, the male greater rhea seems to be a master manager. Alert, affectionate and always there, greater rhea dads seem to have been handpicked by nature herself. When it comes to paternal care, the greater rhea is really greater than most of their more evolved counterparts.

Father's Day: Nature's Top 10 Dads

6. The Mimic Poison Frog

The mimic poison frogs, found in the north-central region of eastern Peru, make the ideal family men. Not only are they the only known species of monogamous frogs, they are also caring and dedicated father.

The female mimic poison frog lays a handful of eggs on to a leaf and two weeks later, when these eggs hatch into tadpoles, the male carries the tadpoles on his back. He then releases them into a pool of water collected inside the Heliconia plant.

When the little tadpoles get hungry, daddy frog calls out to their mother. The mother mimic poison frog releases non-fertile eggs for the young to eat.

Scientists are still baffled over why mimic poison frogs remain monogamous and provide bi-parental care to their young. Whatever the reason, these vibrantly coloured creatures do make for a pretty family photograph.

Father's Day: Nature's Top 10 Dads

7. The Common Midwife Toad

The common midwife toad is found across Belgium, France, Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Portugal, Spain, Switzerland, and Great Britain with a wide range of habitats ranging from tropical and sub-tropical dry forests to temperate deserts and yet faces the threat of extinction.

Named for its childcare abilities, the midwife toad displays unconventional mating and birthing behaviour. Jelly-like strings which have eggs embedded in them are released by the female. The male fertilizes these eggs externally.

The father midwife frog wraps the strings around his hind legs and cares for them for 3 to 8 weeks until they hatch. Once the offspring is attached to him, the male midwife toad will mate again. This way, he may end up fathering as many as 150 eggs.

To keep the eggs moist enough for the baby toads inside to survive, the father midwife frog finds a damp place to rest. He will even go to the extent to entering into water with his offspring still attached to him in order to make sure that the eggs remain moist.

Not only does the father midwife toad keep his eggs moist but he may also release a disinfecting fluid from his body to safeguard his eggs from disease. At the end of the 3-8 weeks, when the tadpoles are about to hatch out of the eggs, the father midwife toad finds a suitable stretch of water that is cool and still enough for the tadpoles to grow into toads.

The midwife toad is a hands-on father that not many can compete with.

Father's Day: Nature's Top 10 Dads

8. The Great Indian Hornbill

The great Indian hornbill have been observed to live up to 50 years in captivity, during which they grow up to be 51 inches tall with a formidable wingspan of 5 feet.

These monogamous birds, known for their loud calls during mating period, raise their young inside tree hollows. The female hornbill makes her nest in a tree hollow and seals the opening with a plaster made of mud and faeces, except for a slit through which she will receive food from her mate while she cares for the infant hornbills.

The father hornbill makes as many as five trips a day to feed his mate. Once the chicks have grown up enough to begin crowding the nest, the mother breaks out of the sealed nest. The parents seal the chicks inside once again and take turns to feed the chicks for up to five months more, until the chicks are old enough to break out of the sealed nest on their own.

Now threatened by depletion of its habitats in the forests of India, Indonesia and Nepal, dads like the great Indian hornbill are really hard to find!

Father's Day: Nature's Top 10 Dads

9. The Red Fox

The red fox has earned a notorious reputation as a sly trickster in several world mythologies. Found all the way from the Artic Circle in the north to Australia in the south, red foxes are social animals that live in groups called skulks or troops.

Like a large joint family, subordinates and non-mating females will help in rearing, grooming and playing with the kits. There are about half a dozen kits in each litter, however litter sizes can go up to 13 kits.

Although they grow up to be fierce hunters, red fox kits are born blind, deaf and without any teeth. They aren’t even red to begin with! New-born kits are fluffy brown fur balls with tiny legs and large heads. They only leave their dens at 3-4 weeks of age.

Once the mother red fox gives birth to her litter, she becomes weak and is unable to hunt. Food gathering then falls upon the father red fox. He hunts and brings back food to his mate and kits every 4 hours, without which his family would not be able to survive. The kits will only venture out of the den at 3-4 weeks of age, until which the parents are responsible for feeding them. The only breaks that the father red fox takes are to play with his children.

Though traditionally seen as a master deceiver, the red fox is a committed dad, in the event of the death of the mother, will raise his children on his own but will never, ever give up on them.

Father's Day: Nature's Top 10 Dads

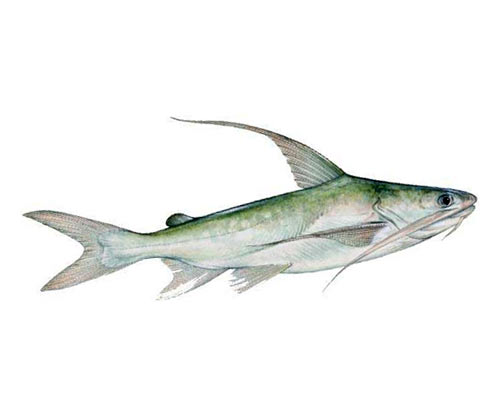

10. The Hardhead Catfish

Found in the waters of Florida Keys and the Gulf of Mexico, the hardhead catfish can grow up to 19.5 inches in length.

It was given its name for the bony plate it has on its head. But hey, don’t judge a fish by its anatomy! This catfish is a class apart when it comes to being a father. The male hardhead catfish is wholly responsible for the wellbeing of his offspring.

Once the female hardhead catfish has laid a clutch of about 24-36 eggs, the male catfish collects them into his mouth, each the size of golf balls. This process is known as mouth-brooding.

To ensure that he doesn’t swallow his eggs, the male hardhead catfish does not eat for the entire mouth-brooding period that lasts for approximately 60 days. The male hardhead catfish will hold his children in the safety of his mouth until they hatch and are able to swim freely.

Although a lot of dads can be hardheaded sometimes, not many can come close to the level of care that the hardhead catfish provides.