Photographs: Supriya Thanawala Supriya Thanawala

Jayashree Ramadas, Dean of the PhD programme in Science Education at the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research, tells us what science education is about, why science needs to be studied in a socially-applicable manner, and some interesting careers in teaching, education, and cognitive science that might follow.

Is science about learning facts and figures, or is it about understanding the world better? Why do we learn chemistry and physics in school, and why are we expected to remember the name of each plant, fauna, animal, and bird in biology class? Does all this have any meaning and significance to our lives or is it just information strewn across pages and pages of textbook print?

These are some of the issues that academicians in the world of science education wish to address. Science education is a new field of study that looks into the ways in which science is taught, the problems with its teaching, the need for connecting classroom learning to day-to-day science, and how children can learn science better.

It is linked to an entire array of interesting new fields and disciplines like cognitive science (the science of thinking patterns), research on the philosophy of science, the formulation and experimentation of new methods in teaching, and teaching itself.

It is with these ideas in mind that the PhD programme in Science Education has been set up by the Homi Bhabha Center for Science Education at the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR). In a chat with Supriya Thanawala, the Dean of the Faculty of Science Education at TIFR, Jayashree Ramadas, talks about some of the problems with classroom education, what they hope to change through their research on science education, and how science can be applied to day-to-day life.

'We find the source of the problems and then come up with solutions'

Photographs: Careers360.com

What is the idea behind having started the PhD programme?

We examine science education right from the time of school to college. There is a problem with the way science is taught; and often, it is the basic concepts that are not clear in the minds of children. There is also a very weak connection between the application of science to every day life, and what is being taught in the classroom. So surely, there is a problem that needs to be addressed.

We look at the source of the problems, and then come up with solutions. On one hand, for instance, there are cognitive problems that children may face, which might affect their basic ability to understand certain concepts. Then, the other aspect is that of the socio-cultural milieu that the child is part of, like the environment around him or her.

We have a small group of students enrolled each year in our PhD programme, and all of them get rigorous, individual attention because they are in such small numbers. Our students-cum-researchers have a background in science, so their concepts are mainly clear. As a backgrounder, we think about issues in the teaching of science, the psychological aspects of learning science, and how science itself has evolved over the years. We also acknowledge how scientists have arrived at their theories -- and this involves the study of the philosophy of science, and the social aspect of science. There are other concepts that we deal with in the history of science and issues in education, and the social contexts that it all emerged from. We tend to ask questions like what the Indian context of science looks like.

We have a good balance between theory and practice. There is a lot of fieldwork that is included in the PhD programme. Students go out to do their research, interact with people, and not just restrict themselves to the classroom.

'Gender biases affect the learning process'

Photographs: Rediff Archives

So who pursues research and work in science education, and why would someone want to do the PhD course at TIFR?

Those who join our programme come from varied backgrounds, but all of them have a basic foundation in science. The one driving motive in all of them is to understand what the process of learning science is all about. They can then apply what they learn about the cognitive and socio-cultural process of science learning -- to the development of mathematics and science education.

What are some of the problems and key issues related to science education right now that you hope to change?

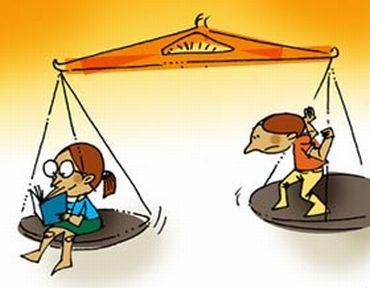

There are various problems that have come up due to the socio-cultural environment in the process of learning in the classroom. This may not have anything to do with the actual subject matter in the first place, and it may include problems like gender biases, for instance.

Today though we have many women in science, they are still only from the urban setup. There are very few women who are participating in science from rural backgrounds. In villages, education itself is still a struggle. But there is also an attitudinal problem to women getting into science.

It is almost taken for granted that women will not be interested in the technical side of things. In most schools, the work experience module is also skewed in terms of gender influence. Cooking classes are assigned to girls, and electronic experience is assigned to boys.

This is not just in the case of science, but it happens even with sports, where boys are encouraged far more than girls are. These gender biases make an impact on the learning process.

'Science in our textbooks emerges out of nowhere'

Photographs: Uttam Ghosh/Rediff.com

What about controversial subjects that fall between the arts and sciences, and what are the different ways in which new teaching methods can be evolved?

There is a school of thought that says that even those subjects that are traditionally thought of as science have social implications attached to it, so it's not as easy to categorise a subject. Teaching needs to connect social contexts with scientific realities.

Through our programme, we look at the teaching of the natural sciences as well as that of mathematics and technology and ways in which it can be improved. We have been trying to find ways of discussing how technology education can be incorporated in schools too, for instance. Exposure and understanding of technology, for instance, is something that has really been missing in our education system.

We have also been looking at whether project based learning is effective. Is it possible to learn through projects, and can one learn through projects? These are issues that need to be studied, and areas that need to be developed.

Is science in India westernised?

I am not sure whether I would say that it has a western influence in particular. I think the problem is more that our textbooks are not situated in any context at all. So rather than a western context, what we have is absolutely no context.

Most of the content in our science textbooks consists of laws and principles that emerge out of nowhere. For instance, there are names of animals and plants mentioned without any geographical context given to their existence. Where do they live? What is the relevance or context to knowing about these animals? None of this is really looked at.

The science education in our country is therefore not really westernised; I would instead say it is rather de-contextualised. Learning has to happen within a context.

'Learning is also too urbanised'

Photographs: Rediff Archives

But is there a particular social context that emerges without it deliberately having been placed?

I would say that the context that emerges is often more often 'urban' than 'western'. Of course, urbanisation itself can be western, but there is a difference in the learning that takes place between urban students and rural students. For instance, the kind of examples that children give, who have been brought up in an urban set up is that of garden plants, for instance.

Tribal children, on the other hand, give examples of forest animals, and trees that grow in forests, and natural fauna and flora. We compared this with the examples cited in the textbooks. Without a doubt, the urban texts all had examples of parrots in a cage, or a rose in a pot -- which are urbanised realities.

'We prepare students to play different roles in the education system'

Photographs: Rediff Archives

What do students do once they are through with the programme?

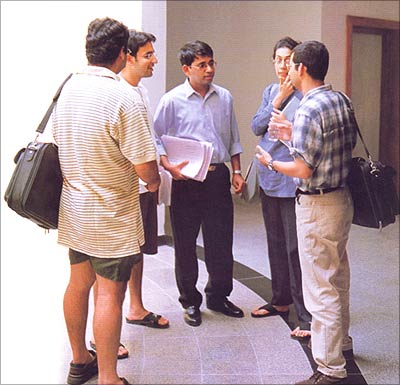

The PhD programme prepares students to play various roles within the education system. Many of the PhD projects involve development of material, and working on new methods, and innovatively looking at different ways of learning.

There are others who get into further research as well. For instance, one of our students is looking at the application of cognitive science to science education, and is now pursuing a post-doctoral project. During her PhD on spatial cognition in science learning, she undertook a one-year teaching intervention, and worked with a group of school students. She taught them astronomy, and designed her teaching in connection to the principles of cognitive science.

She observed how they were learning, looked at the application of spatial-cognitive ideas, and has now come up with a full-fledged teaching module designed on her own. So this is another possibility in itself: working and developing new methods and approaches to teaching itself.

We hope that our students are actively involved in research, but we also hope that they go on to improve science education, write books on it, and apply it. There is a whole range of careers available in writing textbooks as well, and in developing writing material for schools. These are some of the areas where a PhD research in science education can help.

When we select students, we do look at an applicant's oral and written communication skills, but we also attempt to develop these through the course later.

The PhD in Science Education:

Eligibility: A master's degree in any discipline and bachelor's degree in any area of science

Last date to submit applications this year: April 15, 2011

Starting time: The course begins in mid-August

Duration of the programme: 5 years

For further information and details, visit: http://www.hbcse.tifr.res.in/graduate-school or call 022-2507 2100 / 022-2558 0036

Comment

article